Brief Overview

- Hackers have the ability to utilize the Jenkins Script Console for running harmful Groovy codes, which can result in criminal activities like deploying crypto miners.

- Security flaws such as incorrectly configured authentication methods make the /script access point vulnerable to attackers, opening doors for remote code execution (RCE) and misuse by ill-intentioned entities.

- By exploiting weaknesses in Jenkins, malicious actors can execute scripts to download and run a mining program, ensuring persistence through cron jobs and systemd-run utilities.

Jenkins is a free tool that facilitates continuous integration and delivery processes, allowing automation of software development phases like testing, building, and deploying. Despite its benefits, it can serve as an entry point for cybercriminals who prey on misconfigured servers and outdated Jenkins versions to install crypto miners, establish hidden accesses, and gather sensitive data. This blog post delves into how the Jenkins Script Console can be misused for crypto mining activities due to inadequate configuration.

The Script Console in Jenkins serves as a tool that grants the ability for administrators and users with proper authorization to run , Groovy scripts directly on the Jenkins server. This console executes scripts with Jenkins’ access privileges, effectively providing elevated permissions. Jenkins facilitates scripting through the Groovy language.

By default, Jenkins does not allow anonymous users access to the script console. Instead, this console, enabling the execution of Groovy scripts (potentially involving dangerous commands), is restricted to authenticated users possessing administrative permissions. Nonetheless, misconfiguration of a Jenkins instance can occur — for instance, due to improper settings of certain authentication mechanisms — potentially leading to vulnerable instances. Enabling the “Sign Up” or “Registration” option can also expose Jenkins and the /script endpoint to remote code execution risks. Thus, securing this interface adequately is crucial. Unfortunately, certain Jenkins deployments accessible via the internet may be configured incorrectly, rendering them vulnerable to exploitation.

A simple query on Shodan unveils the count of publicly exposed Jenkins servers. While not every exposed Jenkins server might be prone to exploitation, they can still serve as intermediate points for malevolent entities.

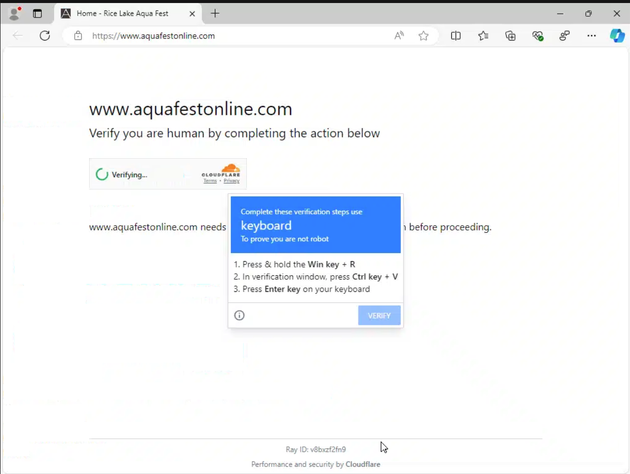

Our observation indicates that when an adversary gains access to the Jenkins Script Console, they possess the capability to execute malicious scripts aimed at cryptocurrency harvesting. Figure 3 showcases the encoded malicious payload discovered during our analysis.

As depicted in the image, the attacker exploits a misconfigured Jenkins Groovy plug-in to execute a Base64-encoded string, which essentially represents a malevolent script.

The examination of this script unfolds as follows:

Initially, this script verifies its operation on BusyBox; if detected, the script will exit:

This script contains a function named svalid() tasked with examining locations equipped with writable permissions:

The function accepts an argument and generates a temporary shell script named vinars in the specified directory. The script simply outputs “ginerd” to the console. It marks this small script as executable and captures the exit status using $?, a unique variable holding a code indicating the outcome of the most recently executed command. This function is later utilized to execute a simple script in a dynamically specified location.

The script ensures it possesses sufficient system resources for efficient mining operations (similar to other cryptocurrency miners). To achieve this, it scans for processes exceeding 90% of the CPU resources, subsequently terminating these processes. Additionally, it halts all inactive processes.

Subsequently, the attacker explores accessible locations where the miner can be retrieved and executed. Initially, it confirms if the present user possesses the write and execution rights for the miner within the /dev/shm directory utilizing the svalid () function; if the function returns a non-zero exit status (indicating the directory lacks write and execute permissions), it proceeds to seek alternative directories except for /proc and /sys.

If an ideal directory cannot be located, it resorts to utilizing /tmp for operations and establishes a subdirectory named duet, assigning it maximum permissions (777).

In the subsequent phase, it initially checks for the presence of the cryptominer binary within the directory. If absent, it downloads the cryptominer binary and incorporates it persistently.To verify the existence of the harmful binary, the script examines the SHA256 checksum.

If this command encounters an error status code, the script proceeds to fetch the malevolent binary, an encoded tar file with the denomination “cex” from https[:]//berrystore[.]me. It employs wget to acquire the binary.

If wget faces difficulties in fetching the file, the OpenSSL’s s_client choice comes into play for retrieving the binary, which establishes a connection to a remote host using SSL/TLS.

This directive dispatches an HTTPS GET request to the server, then retrieves the server’s response, extracting the ultimate 2,481,008 bytes from the input stream, suggesting evasive behavior. The extracted bytes subsequently get stored in the “cex” file.

Functioning as an AES-256 encrypted tar file, OpenSSL is further engaged for decryption. The SHA256 checksum operates for key extraction from the passphrase, whereas AES-256 takes charge of decryption. Following decryption, tar decompresses the file, at which point the authentic “cex” file gets deleted, and executable permission is granted to the file, the same file verified earlier in this script through the “sha256sum app” command.

To ensure the miner’s sustainability, cron job, and systemd-run strategies are executed in conjunction with durability; the flock system utility certifies that a single miner instance operates at any given time.

The content in Figure 13 outlines the creation of a cron job:

- Employing the flock system utility to secure the file, employing /var/tmp/verl.lock file to ensure singular operational instances

- Application of awk ‘!a[$0]++’ to eliminate redundant entries within the cron job. Gel further ensures singular cron job execution.

- Lastly, the awk outcome is channeled into crontab –, upgrading the user’s crontab with refined and unique cron job entries.

The script stores the complete cron job entry in a variable labeled cronny with all the operations to commence mining, including the pool and wallet addresses, and appends this to the crontab.

Utilizing systemd-run for continuousness with persistence

The systemd-run directive incorporates DBUS_SESSSION_BUS_ADDRESS=unix:/run/user/$(id -u)/bus for configuring the DBUS_SESSSION_BUS_ADDRESS environment variable to the D-Bus session bus socket file’s specific address tailored to the prevailing user’s session. This enables applications and services within the user session to communicate through D-Bus.

The intruder then exploits systemd-run to timetable the cryptocurrency mining software’s execution at hourly intervals. The flock utility guarantees singular runtime with a locking mechanism.

Should these techniques falter in executing the miner efficiently, the attacker has an alternate tactic involving execution.

The script fragment executes the subsequent steps:

- Records the content into a file labeled strptr that designates the rig ID for mining operations.

- The “trap ” SIG” command sets up an exemption to the SIG signal. This provision possibly prevents the script from premature cessation due to specific signals.

- The “( sleep 40; kill -9 $PPID ) &” directive launches a background subshell (&) that waits for 40 seconds before issuing a SIGKILL signalcommunicate with the parent process ($PPID), which could be the same script (possibly used to ensure termination of the script after a certain period for cleanup).

- The miner is then executed using the exec command.

In order to safeguard Jenkins servers against the discussed vulnerabilities, we suggest implementing the following best practices:

- Utilize the Script Approval feature offered by Jenkins.

- Enforce proper authentication and authorization mechanisms for accessing the web console. Jenkins provides specific guidelines on Access Control.

- Take advantage of the Audit Logging feature provided by Jenkins.

- Ensure that Jenkins servers are shielded from external internet access.

Threat Hunting Query for Vision One

Below are some potentially valuable queries for threat hunting within Vision One:

- eventSubId: 2 AND processCmd:* exec * –rig-id *

- eventSubId: 2 AND processCmd:cron AND objectCmd:* exec * –rig-id *

Jenkins software’s robust functionalities make it indispensable for contemporary software development. However, these capabilities also pose significant risks when misconfigured or left unpatched (as highlighted in our previous Jenkins blog post). In this blog entry, we explore how attackers can exploit the Jenkins Script Console to deploy malicious scripts like cryptocurrency mining operations.

Configuring Jenkins correctly, implementing strong authentication and authorization controls, conducting regular audits, and restricting internet access to Jenkins servers are all crucial steps for organizations to notably reduce the chances of their Jenkins instances being used as attack vectors and to safeguard their development environments from exploitation.

You can find the indicators of compromise for this entry here.

MITRE ATT&CK Techniques

| Tactic | Technique | Technique ID |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Access | Exploit Public-Facing Application | T1190 |

| Discovery | Process Discovery | T1057 |

| File and Directory Discovery | T1083 | |

| Defense Evasion | File and Directory Permissions Modification: Linux and Mac File and Directory Permissions Modification | T1222.002 |

| Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information | T1140 | |

| Command and Control | Ingress Tool Transfer | T1105 |

| Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols | T1071.001 | |

| Persistence | Scheduled Task/Job: Cron | T1053.003 |

| Scheduled Task/Job: Systemd Timers | T1053.006 | |

| Impact | Resource Hijacking | T1496 |

Tags

sXpIBdPeKzI9PC2p0SWMpUSM2NSxWzPyXTMLlbXmYa0R20xk