This blog is a segment in a series regarding Earth Kasha. Please refer to our earlier blog posts discussing Earth Kasha’s methodologies and objectives in depth, available here for further details,

Synopsis

Based on research conducted by Trend Micro, a recent spear-phishing operation aimed at individuals and organizations in Japan has been ongoing since approximately June 2024. A notable aspect of this operation is the reappearance of a previously known backdoor named ANEL, last utilized in campaigns by APT10 that targeted Japan until around 2018 and had not been active since then. Furthermore, the presence of NOOPDOOR, a tool associated with Earth Kasha, has also been identified in this operation. These insights indicate that this operation is part of a fresh initiative by Earth Kasha.

Operation Insights

The operation, noted around June 2024 and attributed to Earth Kasha, involved the use of spear-phishing emails for Initial Access. Specific targets encompassed individuals linked to political organizations, research institutions, think tanks, and bodies dealing with international affairs. In 2023, Earth Kasha predominantly focused on leveraging vulnerabilities in edge devices for intrusion attempts. However, this recent campaign indicates a shift towards different tactics, showcasing their continuous evolution in attack strategies.

once again altered their Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures. This change seems to be motivated by a shift in targets, transitioning from corporations to individuals. Moreover, an examination of the victim profiles and the names of the bait files distributed indicates that the adversaries have a special interest in subjects concerning Japan’s national security and global relations.

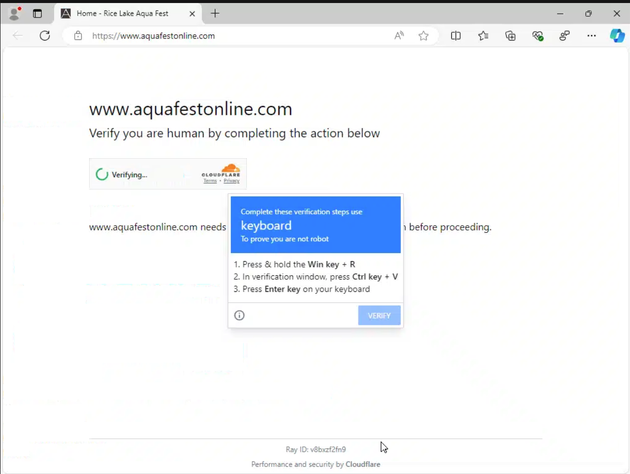

The phishing emails deployed in this operation were dispatched from either costless email accounts or compromised accounts. These emails featured a hyperlink to a OneDrive. They carried a message in Japanese urging the recipient to retrieve a ZIP file. Below are some potential email subjects observed, likely designed to capture the attention of the targeted recipients:

- Interview Request Form (取材申請書)

- Japan’s Economic Security in Light of Current US-China Relations (米中の現状から考える日本の経済安全保障)

- [List of Government and Public Institutions] ([官公庁・公的機関一覧])

The content within the ZIP file, serving as the infection carrier, varies based on the timeframe and the objective.

Scenario 1: Macro-Enabled Document

The most straightforward scenario involves a document embedded with macros. The infection commences once the document is opened and the user authorizes the macros. This document file acts as a malicious dropper dubbed as ROAMINGMOUSE. As elaborated later on, ROAMINGMOUSE can extract and execute embedded ANEL-associated components (a valid EXE, ANELLDR, and encrypted ANEL). Two distinct patterns are discerned in this process: one entails dropping a ZIP file followed by its extraction, while the other involves directly dispensing the components.

Scenario 2: Shortcut + SFX + Macro-Enabled Template Document

In other instances, the ZIP file did not directly contain ROAMINGMOUSE. Instead, it housed a shortcut file and an SFX (self-extracting) file camouflaged as a document through alterations in its icon and extension.

Once the shortcut file is activated, it runs the SFX file in the same directory masked as a .docx file.

The SFX file deposits two document files into the %APPDATA%MicrosoftTemplates directory. One of these files acts as an innocuous distraction, while the other, labeled “normal_.dotm,” contains a macro named ROAMINGMOUSE. When the decoy document is launched, ROAMINGMOUSE is automatically loaded as a Word Template file. ROAMINGMOUSE’s behavior post-execution mirrors what was witnessed in Scenario 1.

Scenario 3: Shortcut + CAB + Macro-Enabled Template Document

A parallel case to Scenario 2 emerged, where the shortcut file triggers PowerShell, subsequently dropping an embedded CAB file.

In this particular case, the shortcut file contained a PowerShell one-liner, illustrated in the figure below. This script dropped and unzipped a CAB file embedded at a particular offset within the shortcut file and executed a decoy file. The decoy file then automatically loaded ROAMINGMOUSE as a template file, following the same progression as in Scenario 2.

Malware on Initial Access

ROAMINGMOUSE

The macro-enabled document devised for the first point of contact in this operation is named “ROAMINGMOUSE.” This document functions as a carrier for ANEL-related components. The primary objective of ROAMINGMOUSE is to execute the ensuing ANEL payload while reducing the chances of detection. In order to accomplish this, it incorporates various evasion methods.

(Basic) Sandbox Evasion

The variant of ROAMINGMOUSE introduced in Scenario 1 mandates the user to authorize macros. This variant contains a feature that triggers malicious activities based on specific mouse movements executed by the user. This functionality is realized by implementing a function that responds to the “MouseMove” event invoked when the mouse hovers over a user form embedded within the document.

This feature ensures that nefarious actions do not commence unless specific user interactions take place, which is likely implemented as a technique to evade sandboxing. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that numerous commercial and open-source sandboxing solutions have tackled such evasion techniques in recent times, reducing their effectiveness.

Custom Encoded Payloads

The characterization of this as an evasion strategy is open to discussion; nonetheless, it is unquestionably a unique attribute of ROAMINGMOUSE. This approach was utilized in Pattern 1 of Case 1. ROAMINGMOUSE incorporates the ZIP file containing the ANEL-linked elements by encoding it in Base64 and segmenting it into three sections, with one segment encoded using a personalized Base64 encoding table. The contents from the ZIP file are then extracted to a designated path.

This method may introduce delays in analysis, but it could also function as an evasion tactic against contemporary tools that automatically decode Base64 strings embedded in VBA. Such tools have gained prevalence recently, potentially making this a viable countermeasure.

Hex Encoded Payloads

In specific instances, as seen in Case 1 and PATTERN 2, occurrences were noted where the ANEL-related elements were directly deployed without undergoing processing through a Base64-encoded ZIP file. Each element was incorporated in the VBA code as HEX-encoded strings in these instances.

Execution Via WMI

The deployed files encompass the subsequent ANEL-associated components:

- ScnCfg32.Exe: An authentic application that loads the DLL from the same directory via DLL sideloading.

- vsodscpl.dll: The ANELLDR loader.

- <RANDOM>: The encrypted ANEL.

ROAMINGMOUSE executes ANEL by initiating the legitimate application “ScnCfg32.exe,” which loads the malevolent DLL “vsodscpl.dll” through DLL sideloading. It leverages WMI to launch “explorer.exe” with “ScnCfg32.Exe” as a parameter in this operation.

This methodology aims to skirt detection by security products, which are more inclined to flag processes like “cmd.exe” when launched directly from a document such as a Word file. By bypassing “cmd.exe” and executing the program through WMI, they seek to evade these detection measures.

ANELLDR

We have been monitoring the distinctive loader utilized to execute ANEL from memory, which we have dubbed ANELLDR. ANELLDR has been detected as early as 2018. In terms of its operational capabilities, the version employed in this initiative mirrors the one used in 2018. In addition to its core functionality, ANELLDR has a reputation for employing anti-analysis techniques like junk code insertion, Control Flow Flattening (CFF), and Mixed Boolean Arithmetic (MBA). The ANELLDR observed in this campaign also integrates these methodologies.

While there exist some publicly accessible details about ANELLDR, a comprehensive delineation of its behavior is still warranted. We will furnish an exhaustive elucidation of the loader’s functions.

ANELLDR is initiated via DLL sideloading from a legitimate application to commence its malicious operations. Upon activation, it scans files in the present directory to locate encrypted payload files. Significantly, the decryption methodology of ANELLDR varies during the initial and subsequent executions.

During the first execution, ANELLDR computes the Adler-32 checksum for the last four bytes of the target file and the data up to the file size minus 0x34 bytes (where 0x34 bytes infer the 0x30 bytes of AES material and 0x4 bytes of checksum, elucidated later). It subsequently compares the checksum to verify if the target file aligns with the anticipated encrypted file. If a directory exists at the same level, it iterates through the files within that directory.

On passing the verification phase, the decryption process commences. For this, the final 0x30 bytes of the file are split into two segments: the initial 0x20 bytes represent the AES key, while the remaining 0x10 bytes serve as the AES IV. ANELLDR then decrypts the encrypted content (up to the file size minus 0x34 bytes) through AES-256-CBC and proceeds to execute.the data in RAM.

If ANELLDR decrypts the encoded payload successfully, it refreshes the key and IV, encrypts the payload with AES-256-CBC, and substitutes the original encoded payload file with the new encrypted information. The AES key and IV utilized for this task are created based on the file path of the executing file and a hardcoded phrase. This employs a unique Base64 encoding, the Blowfish encryption technique, and XOR operations to ensure the key and IV are distinct to the operational setting. As the AES key and IV for encryption are not included in the file, the specific file path where the payload was initially saved must be known to decode an encrypted payload file acquired from a compromised environment.

The Secondary Shellcode

The decrypted details are shaped into a shellcode and executed in RAM. This secondary shellcode is accountable for loading and running the definitive payload, a DLL, in RAM. Initially, the secondary shellcode endeavors to avoid detection by calling the ZwSetInformationThread API with the second parameter set to ThreadHideFromDebugger (0x11). Then, it acquires the position of the encoded information. To accomplish this, it invokes a unique function packed with NOP commands to determine the present address in memory. Subsequently, upon obtaining this address, it computes the location of the data related to the encoded payload, situated directly after this function.

The encrypted data segment follows this outline:

ANELLDR deciphers the subsequent encoded data utilizing a 16-byte XOR key. A notable aspect of this procedure is that every byte of the encoded data is XORed with the entire 16-byte key. Essentially, the algorithm performs XOR on each data byte 16 times, employing a distinct key byte for each iteration.

Post the XOR operation, the data is uncompressed utilizing the Lempel–Ziv–Oberhumer (LZO) data compression approach. Additionally, the initial 4 bytes and the Adler-32 checksum of the payload DLL are computed and contrasted to confirm whether the information has been accurately decoded and uncompressed. If the validation passes, the DLL is dynamically initialized in RAM, and the fixed export function is invoked to execute the payload.

ANEL

ANEL is a 32-bit HTTP-oriented backdoor that has been detected since approximately 2017 and was recognized as one of the primary backdoors employed by APT10 until about 2018. ANEL saw active development during that era, and the most recent publicly acknowledged version in 2018 was “5.5.0 rev1.” Nonetheless, through this fresh campaign in 2024, versions “5.5.4 rev1,” “5.5.5 rev1,” “5.5.6 rev1,” and “5.5.7 rev1” have been noted, along with a freshly identified edition where the version specifics have been concealed.

|

|

5.5.0 rev1 |

5.5.4 rev1 |

5.5.5 rev1 |

5.5.6 rev1 |

5.5.7 rev1 |

unknown |

| Command & Control Communication Encryption (GET) | Custom ChaCha20 + random-byte XOR + Base64 | |||||

| Command & Control Communication Encryption (POST) | Custom ChaCha20 + LZO | |||||

| ChaCha20 Key Generation | Chosen from the hardcoded key based on the Command & Control URL | |||||

|

Backdoor Command |

|

|

||||

Here, we will closely examine the specific enhancements.

and modifications with each edition.

5.5.4 rev1

In this ANEL version, there were no significant alterations, but some minor corrections and enhancements were made. A noteworthy amendment was the elimination of a feature that previously stored an error code in the HTTP Cookie header and transmitted it to the C&C server. This feature existed up to the “5.5.0 rev1” version. The exclusion of this feature, which was previously a detection indicator for ANEL, may have been intended to avoid detection. Another update concerned the version data sent to the C&C server. It now incorporates details about the OS architecture of the running environment. Even though ANEL is a 32-bit application, if it operates on a 64-bit OS, the version data includes the addition of “wow64” before being sent to the C&C server.

5.5.5 rev1

The “5.5.5 rev1” version did not introduce significant changes either. One notable update was the incorporation of code to refresh the local IP address during the initial connection to the C&C server.

5.5.6 rev1 / 5.5.7 rev1

In the “5.5.6 rev1” version, a new backdoor command was introduced. ANEL processes the command string received from the C&C server by converting it to uppercase, hashing it with xxHash, and then comparing it to a predetermined hash value to identify the command. This version included a new command associated with the hash value “0x596813980E83DAE6.”

This specific command allows for the execution of a specified program with heightened privileges (Integrity High) by exploiting the CMSTPLUA COM interface, a recognized UAC circumvention technique.

Conversely, in “5.5.7 rev1,” no other noteworthy functionalities were detected.

Unknown version

Following the observation of version “5.5.7 rev1,” an ANEL variant was identified with concealed version details. In this scenario, the version data field contained a Base64-encoded sequence, resulting in the data “A1 5E 99 00 E7 DE 2B F5 AD A1 E8 D1 55 D5 0A 22” after decryption. This information was concatenated with “wow64” and dispatched to the C&C server. This alteration has made it more challenging to monitor versions and compare functionalities.

Post-Exploitation Activities

Examination of the adversary’s actions post-ANEL installation unveiled their data collection from the infected environment, which involved capturing screenshots and running commands like arp and dir to amass network and file system specifics. In certain instances, supplementary malware, notably NOOPDOOR, was also deployed.

NOOPDOOR, recognized since at least 2021, is a modular backdoor with advanced functionalities. It appears to be used as an additional payload by Earth Kasha, particularly for high-priority targets. This campaign indicates that NOOPDOOR was utilized against specially targeted entities of interest to the adversary.

Attribution and Insights

Following the evaluation of the ongoing operation, Trend Micro affirms that the spear-phishing campaign employing ANEL, observed since June 2024, is part of a fresh initiative orchestrated by Earth Kasha.

The attribution to Earth Kasha is supported by the following factors:

- Until early 2023, Earth Kasha had pursued campaigns aimed at individuals and organizations in Japan through spear-phishing emails as the primary intrusion approach. There are no significant discrepancies regarding TTPs or victim characteristics.

- NOOPDOOR, commonly associated with Earth Kasha, was also leveraged in this campaign.

- As previously noted, there are resemblances in code between ANELLDR and NOOPDOOR, indicating the involvement of the same coder or someone with access to both source codes. Therefore, the reuse of ANEL in this campaign is not surprising and reinforces the link between the former APT10 and the current Earth Kasha.

Trend Micro Vision One Threat Intelligence

To anticipate evolving threats, Trend Micro clientele can access various Intelligence Reports and Threat Insights within Trend Micro Vision One. Threat Insights assist clients in staying ahead of potential cyber threats and better prepared for emerging risks. It delivers comprehensive details on threat actors, their malevolent actions, and the methodologies they employ. Leveraging thisWith intelligence, clients can preemptively safeguard their systems, minimize vulnerabilities, and effectively react to dangers.

Application for Intelligence Reports by Trend Micro Vision One [IOC Sweeping]

- Guess Who’s Back? ANEL’s Resurgence in the Latest Spear-phishing Campaign by Earth Kasha in 2024

Application for Threat Insights by Trend Micro Vision One

Hunting Queries

Application for Search by Trend Micro Vision One

Clients of Trend Micro Vision One can utilize the Search App to correlate or seek out the malevolent indicators referenced in this blog post within their systems.

Identification of malware linked to the spear-phishing campaign by Earth Kasha

(malName:*ANEL* OR malName:*ROAMINGMOUSE*) AND eventName: MALWARE_DETECTION

Malevolent IPs employed by ANEL in the spear-phishing campaign of 2024

eventId:3 AND (dst:”139.84.131.62″ OR dst:”139.84.136.105″ OR dst:”45.32.116.146″ OR dst:”45.77.252.85″ OR dst:”208.85.18.4″ OR src:”139.84.131.62″ OR src:”139.84.136.105″ OR src:”45.32.116.146″ OR src:”45.77.252.85″ OR src:”208.85.18.4″)

Additional hunting queries are accessible to Vision One customers with Threat Insights Entitlement enabled.

YARA rule

This specific YARA rule could be utilized for identifying Earth Kasha’s operations.

Summary

The campaigns by Earth Kasha are foreseen to progress further, incorporating enhancements to their tools and TTPs. A significant number of the targets are individuals, like researchers, who might possess varied security measures in comparison to corporate entities, thereby rendering these assaults harder to detect. It’s imperative to uphold fundamental countermeasures, such as refraining from opening attachments in suspicious emails. Furthermore, it’s crucial to amass threat intelligence and ensure that relevant parties are notified. Given that this campaign is assumed to be active as of October 2024, sustained alertness is indispensable.

Indicators of Compromise

The comprehensive list of IoCs can be accessed here.

Tags

sXpIBdPeKzI9PC2p0SWMpUSM2NSxWzPyXTMLlbXmYa0R20xk