Review of Fool’s Gold: dissecting a counterfeit gold market swindle by Jonathon Idar

Throughout the past 18 months, we have been monitoring the continuous growth and development of deception groups utilizing counterfeit mobile applications and interactions across prevalent messaging platforms to entice individuals into investment ploys. They employ emotional triggers, curated visuals, and media, together with skillfully crafted manipulations alongside sophisticated mobile app architecture to instill trust in victims gradually and coerce them into relinquishing their personal finances.

These fraudulent activities, which we labeled as “CryptoRom” in our earlier investigations, became known in China as sha zhu pan (杀猪盘) (“pig butchering”). The scam format originated in China and expanded globally during the COVID 19 outbreak—partly due to crackdowns on crypto-related crimes by the Chinese government and other fraudulent activities in China, and partly due to increasing opportunities resulting from economic difficulties stemming from the pandemic.

In our past analyses, we have traced how the perpetrators transitioned from targeting individuals in Chinese-speaking communities to a broader audience, and the level of their technical capabilities. We recently unveiled two deceptive rings that had successfully released applications on the Apple iOS App Store, circumventing Apple’s stringent examination process. Pig butchering scammers are now widening their reach, aiming at victims in Western nations using the same tactics that proved effective across Asia.

As we persist in our examination of the criminal entities orchestrating these deceits, I have continued to explore the strategies, tools, and protocols shared among them, and keep an eye out for developing patterns. To demonstrate their prevalence, I was directly targeted by multiple rogue operations, with each carrying out distinct variations of pig butchering. I engaged with two of these fraudulent operations in an attempt to expand our understanding of them, also acquiring the fake trading apps they operated and details regarding their supportive infrastructure and organizational procedures.

The first of these, which I discuss in this article, was conducted by a group based in Hong Kong that misused the MetaTrader 4 application—a legitimate trading tool from a Russian software firm that had been exploited previously—to facilitate a sham gold-trading platform. They distributed Windows, Android, and iOS versions of the application, downloadable from a fraudulent bank portal; the iOS app utilized an enterprise mobile device management strategy to deploy to victims’ devices. To become a participant in the trading platform, victims were required to submit substantial personal details, including copies of official identification documents and tax ID numbers, and later transfer funds to the scammers.

The second deception (outlined in an upcoming report) was orchestrated by a Chinese syndicate based in Cambodia that operated a fictitious cryptocurrency trading app using the TradingView brand. The app, available on a counterfeit app store, was provided in Android and iOS “web clip” editions. This scheme involved a more sophisticated social engineering setup but adhered to the same pig butchering formula. Wallets linked to the deceptive app showcased transactions of approximately $500,000 US in cryptocurrency from victims within a one-month period.

We have shared information about these deceits with Apple and Google, as well as other entities that were impersonated in the ploys or exploited as part of the fraudulent chain. We have also cooperated with the companies furnishing infrastructure to the scams and relevant CERT teams to support their takedown operations.

Both fraudulent activities are still ongoing. This is mostly due to the challenge of convincing infrastructure operators to take action against them promptly, and the recurrent nature of these operations—when one set of app authorizations and infrastructure is dismantled, another promptly emerges to take its place.

Engagement with Fake Accounts

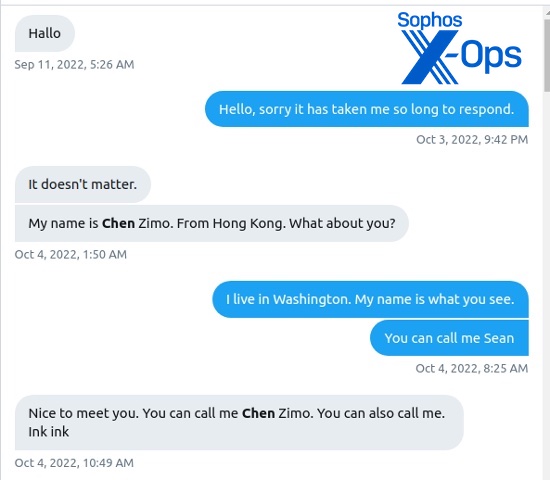

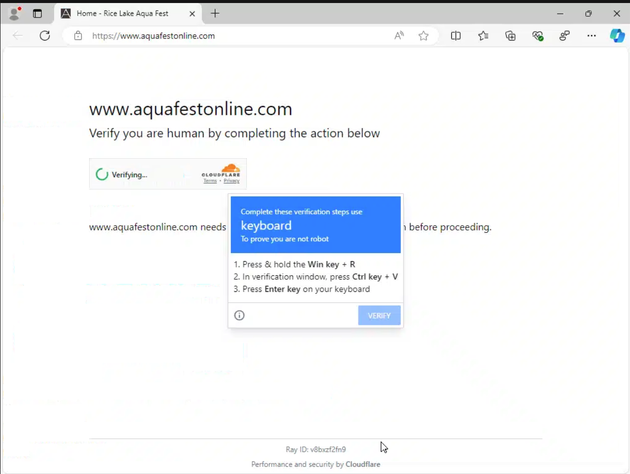

The initial scammer I interacted with approached me similar to the liquidity mining scam we previously exposed—via a direct message on Twitter. In fact, I left the message unattended for almost a month before responding on October 3.

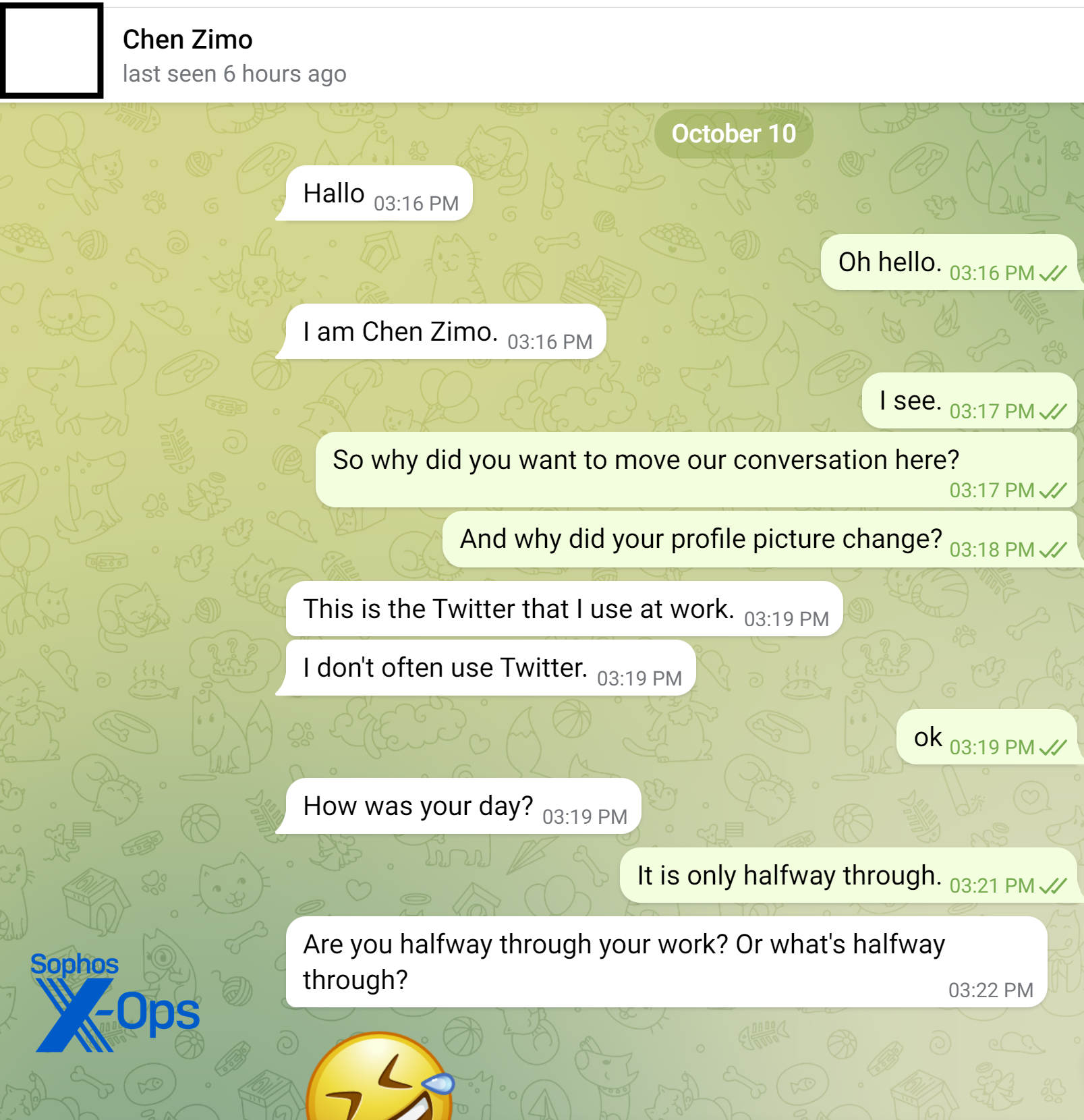

Initiating with a simple “Hallo,” the scammer engaged me through direct messages on Twitter to assess if I was a viable target for the deceit. Claiming to be a 40-year-old woman from Hong Kong, the individual swiftly altered the account screen name from “Alice” to “Chen Zimo” after I began responding. This Twitter profile is still active, notwithstanding being reported.

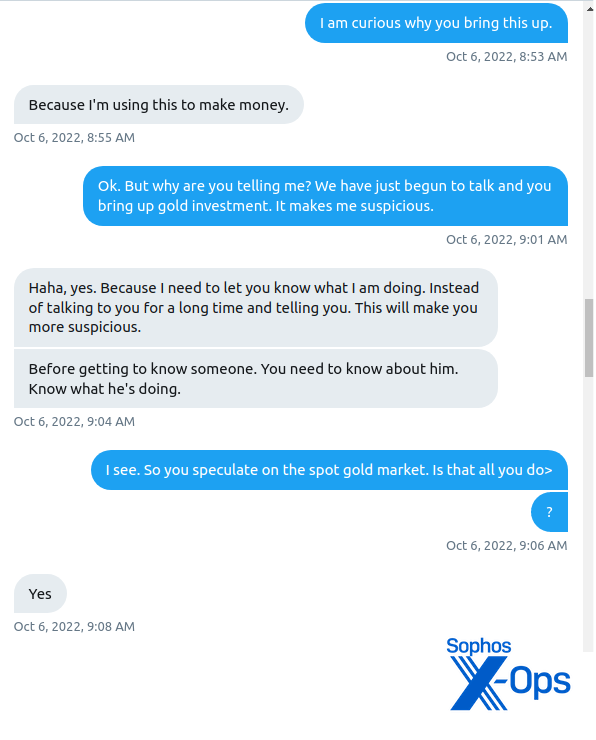

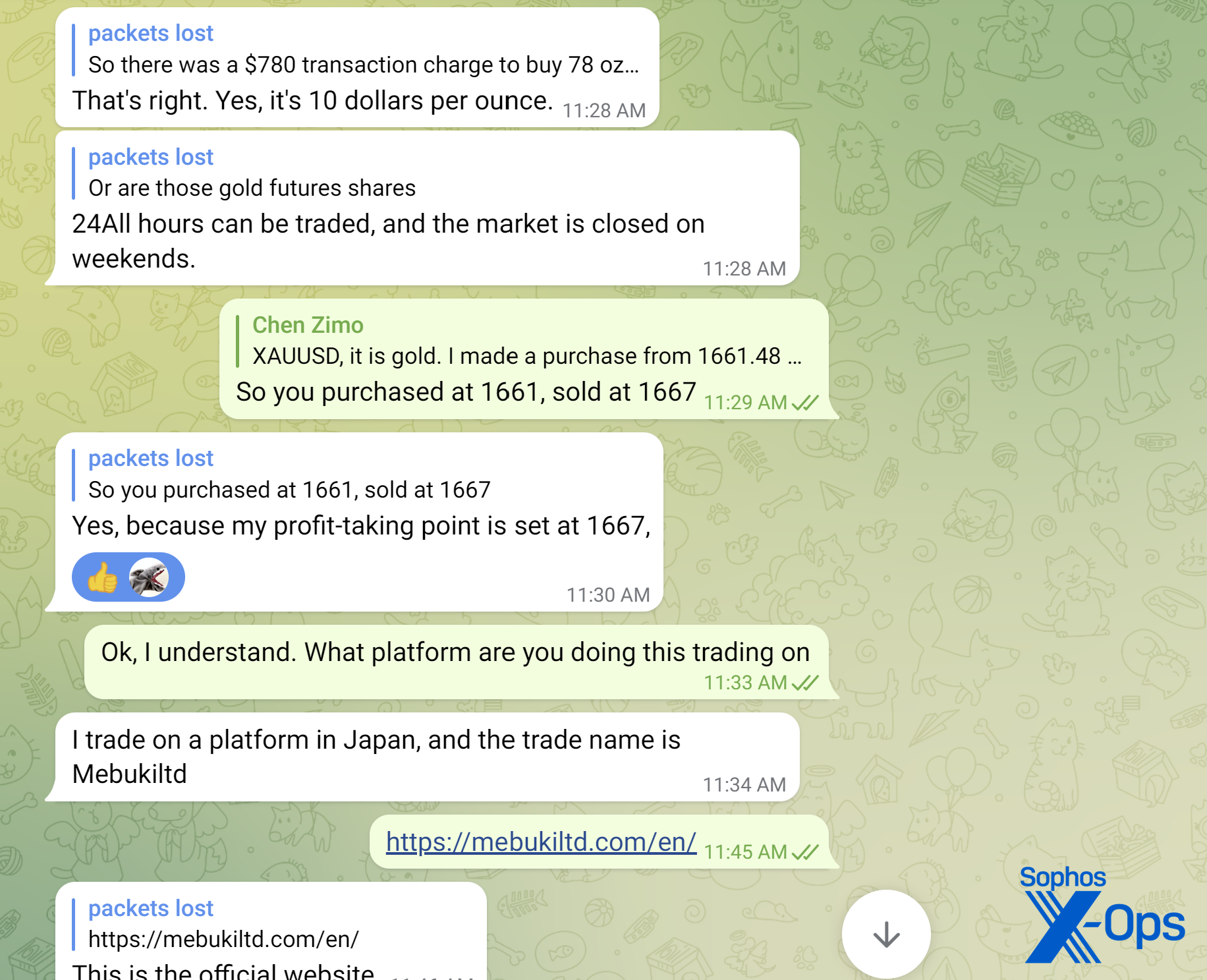

Identifying myself as a cybersecurity researcher specialized in threat assessments, I disclosed that I probe into fraudulent activities. The scammer inquired, “So, are you a cop?” to which I replied in the negative, prompting the conversation to shift swiftly towards investment opportunities, particularly in the gold market, as depicted below.

Skeptical of the rapid progression in the dialogue, I expressed my doubts. The scammer attempted to clarify that this was an act of transparency, in fact:

I allowed the conversation to pause for several days.

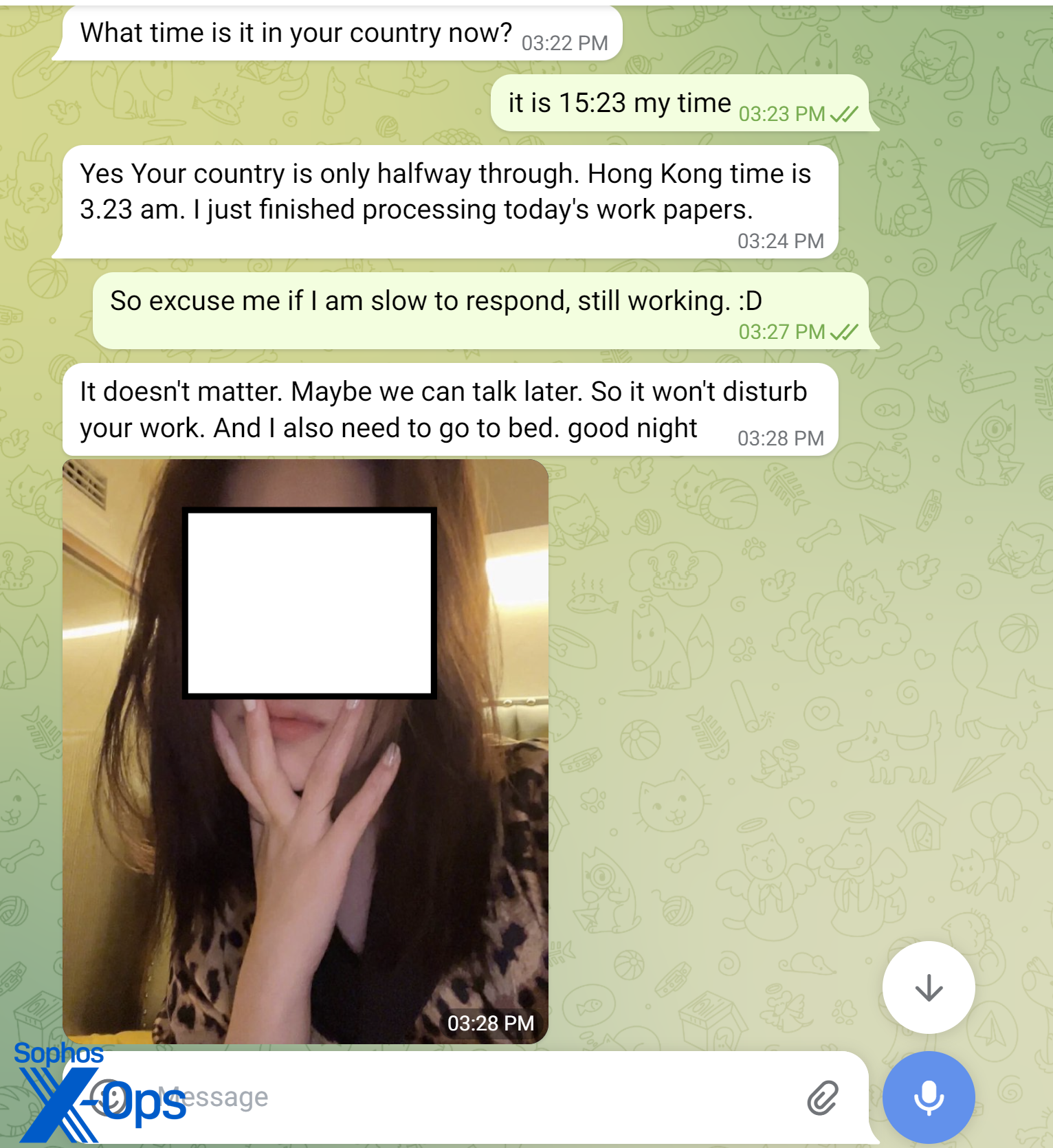

Upon resuming the message exchange, the deceiver redirected the discussion away from Twitter, initially inquiring if I utilized WhatsApp. I mentioned that I did not, but that I utilized Telegram. The individual affirmed that Telegram was also acceptable and requested my username.

The Telegram profile of the individual displayed a visible phone number affiliated with a UK mobile network. Upon checking carrier details, it was revealed that the number belonged to a provider offering support for 3G legacy systems and WiFi calls—effectively categorizing it as a VoIP service. After adding the Telegram account to my contacts, the scammer promptly altered their alias (initially “Alice”) to “Chen Zimo” to align with the Twitter account, albeit before the initial Telegram message.

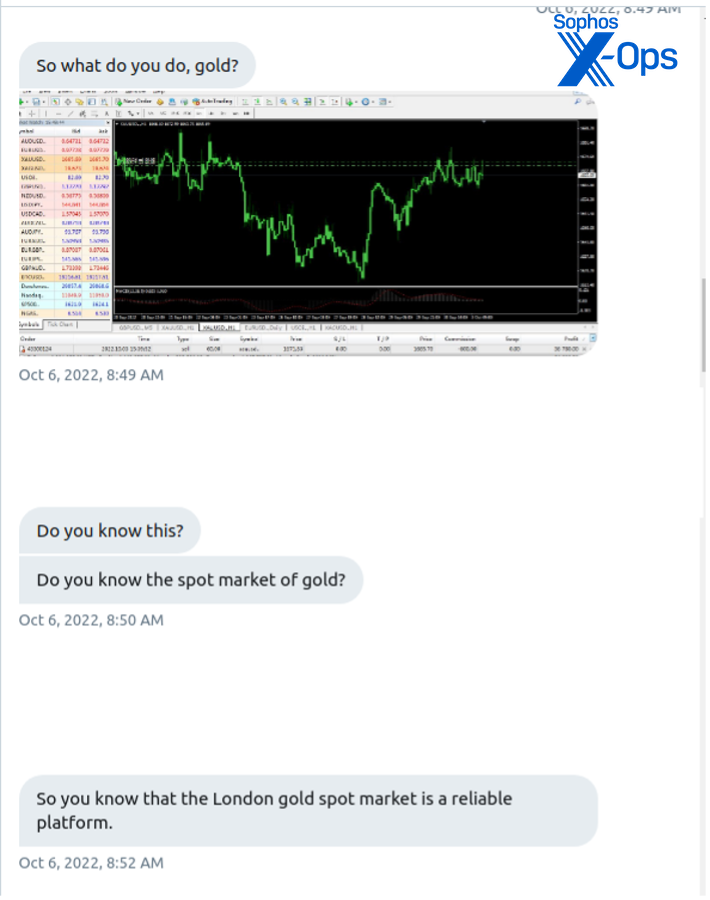

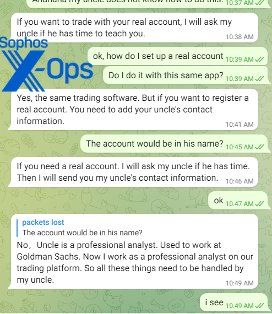

“Chen” shared that “her” uncle had instructed her in short-term trading on the London precious metal market. Without adopting a blatant sales-oriented pitch, the majority of the content conveyed by the fraudster emphasized “gold trading”:

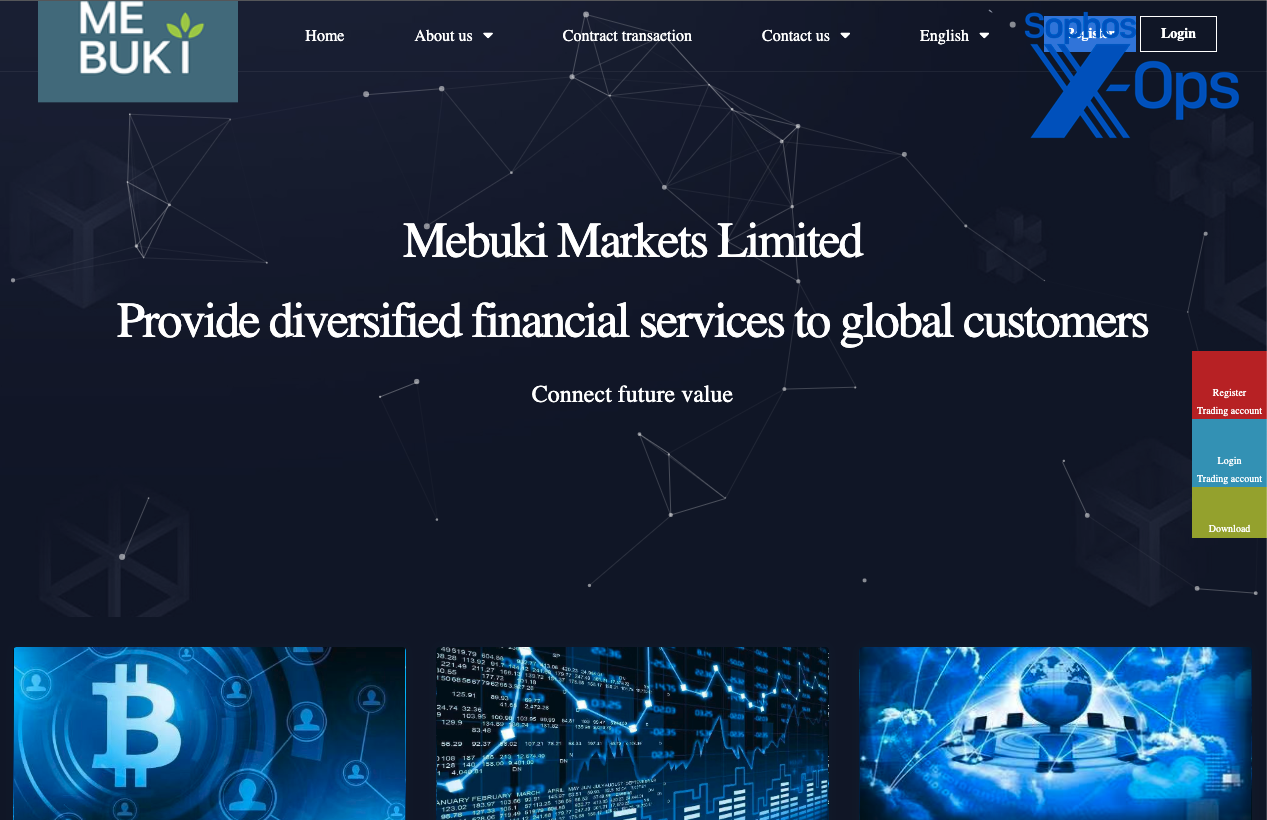

I raised inquiries regarding the trading platform they utilized. “Chen” furnished a name, prompting a rapid online search on my part. The fraudulent website, leveraging effective search engine optimization—featuring fabricated reviews on a foreign currency exchange monitoring platform—ranked higher in search results compared to the legitimate company’s website that the scam sought to mimic—a Japanese financial institution. The website purported to offer currency exchange and commodity trading services.

I raised inquiries regarding the trading platform they utilized. “Chen” furnished a name, prompting a rapid online search on my part. The fraudulent website, leveraging effective search engine optimization—featuring fabricated reviews on a foreign currency exchange monitoring platform—ranked higher in search results compared to the legitimate company’s website that the scam sought to mimic—a Japanese financial institution. The website purported to offer currency exchange and commodity trading services.

The scammer identified the platform

The fabricated website, registered in Hong Kong.

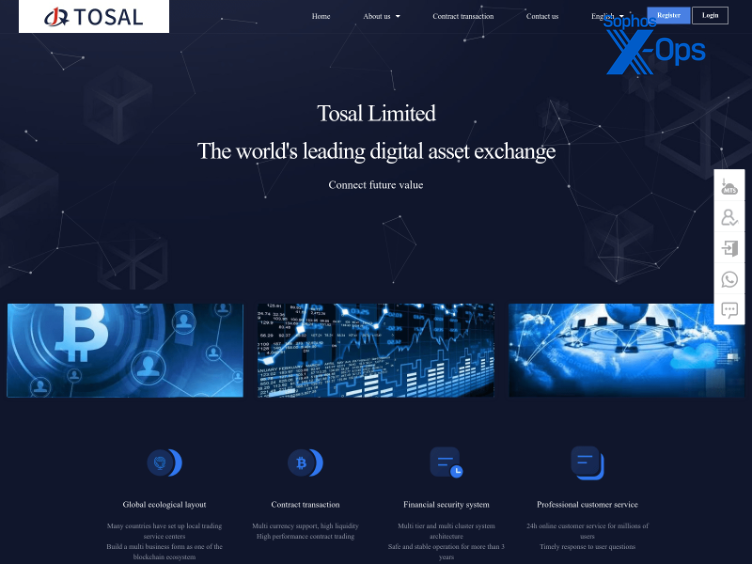

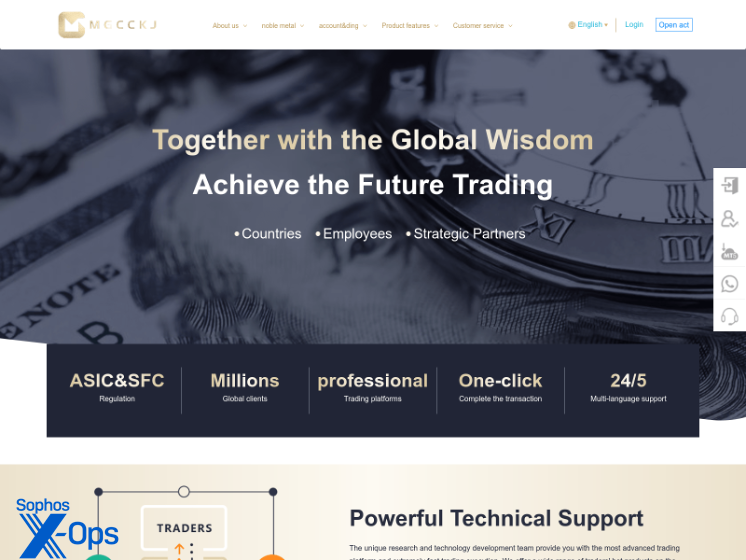

A review of the server hosting the website unveiled nearly identical sites for several other brands, one of which adopted the same template. The server was managed by Shenzhen Balian Network Technology Co. in Hong Kong. Subsequent investigations uncovered 5 additional websites operating the same deceptive tactic, each under a different brand:

Expressing some reservations regarding the website and retrieving samples from the linked applications, I queried: “Why is the server based in Hong Kong? Why isn’t it hosted where the genuine company’s website is?”

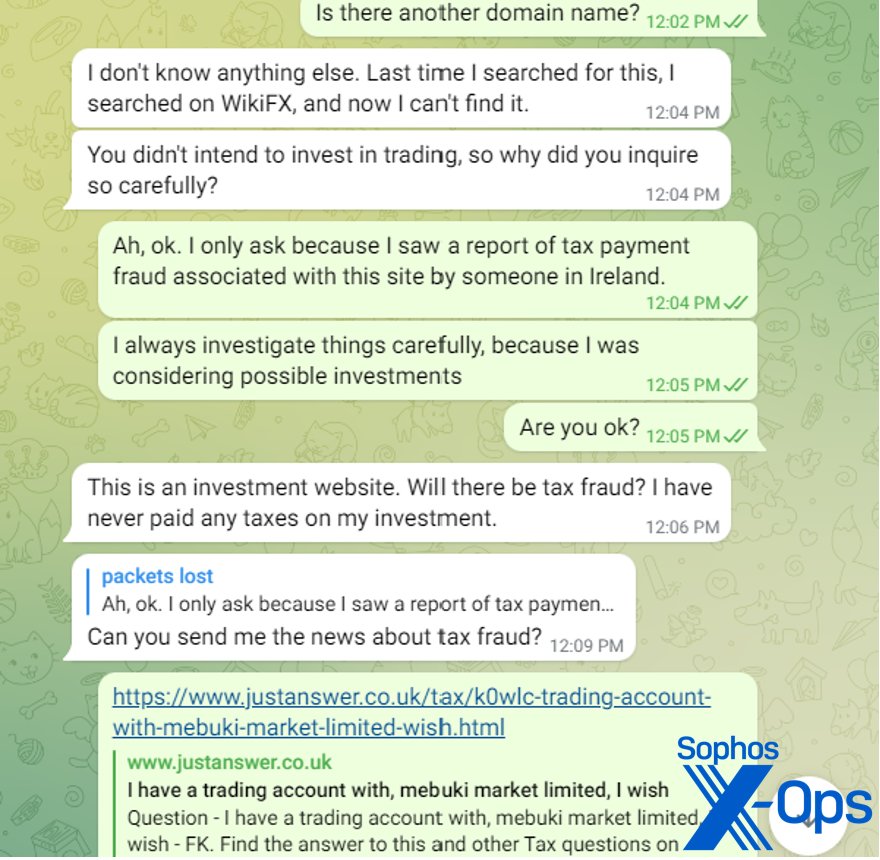

The moment the fraudster began grumbling about my investigation, I stumbled upon a mention of the website on a UK tax inquiry platform. On this site, an “investor” sought advice about tax obligations on profits before making withdrawals. This practice is commonly seen in deceitful schemes intending to milk victims dry. They typically deceive victims, claiming they must pay up to 20% of their fictitious earnings as taxes upfront before allowing any withdrawals, after which they sever contact with the victim.

The scammer assured me that no taxes applied to this investment, as they were already factored into the trading fees, and they claimed to have never paid taxes on transactions in Hong Kong.

The scammer assured me that no taxes applied to this investment, as they were already factored into the trading fees, and they claimed to have never paid taxes on transactions in Hong Kong.

One aspect in which she told the truth was her whereabouts. I discreetly shared a tracking token during our conversation, confirming that she was using an iOS device in Hong Kong.

The fraudster maintained the conversation, elaborating on silver deals and other fabrications. I feigned interest in learning more about “her” activities, with the intention of gathering additional technical insights.

Authorized applications

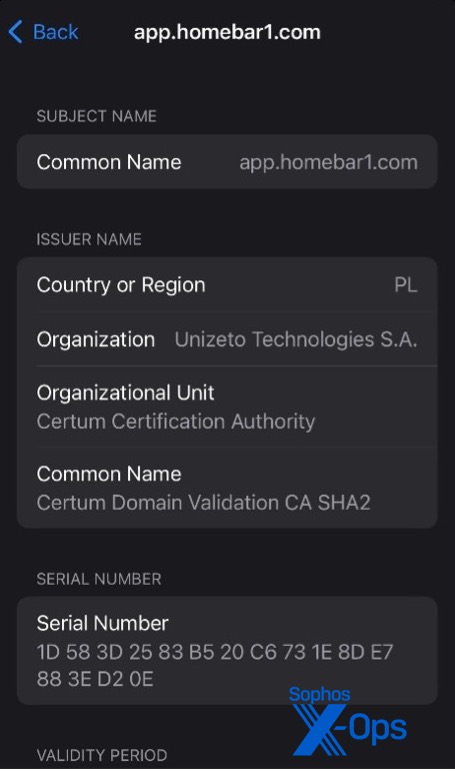

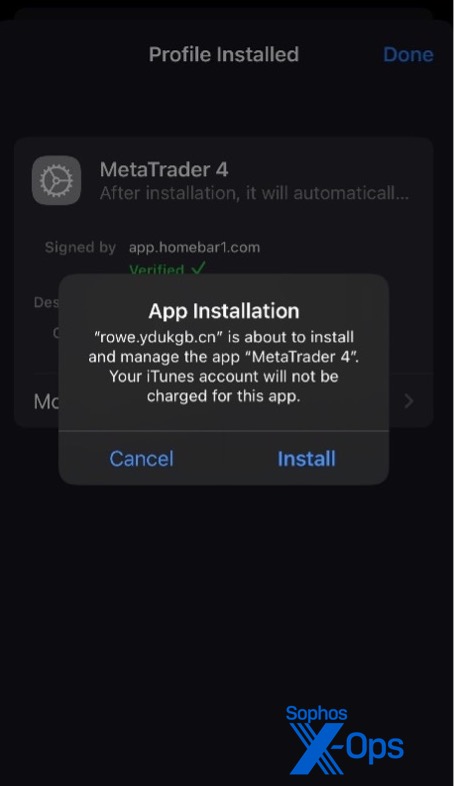

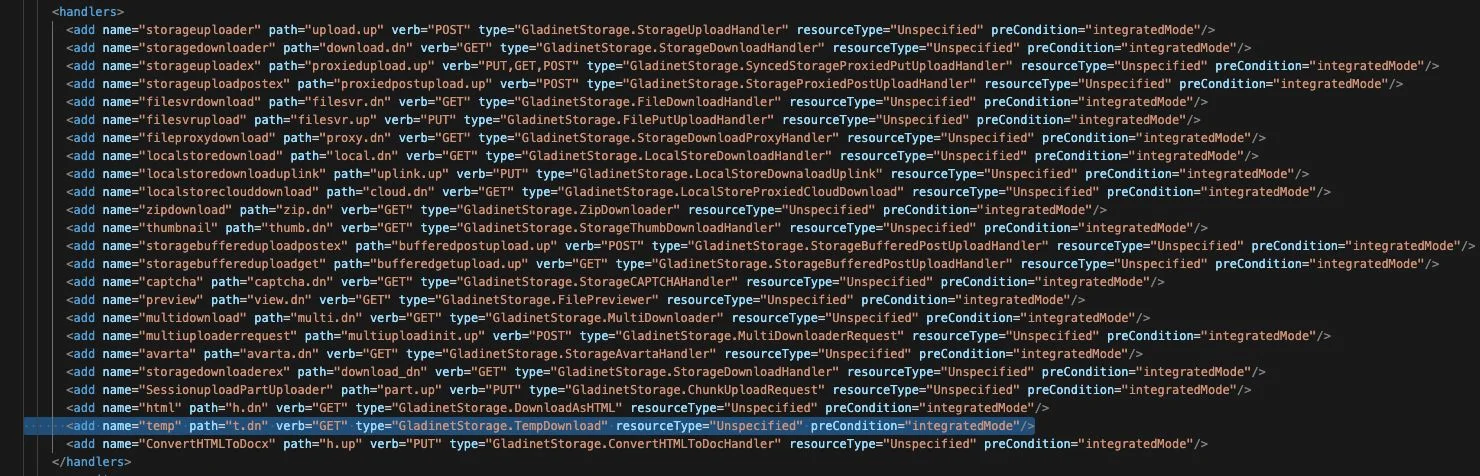

Pleasantly surprised by my sudden interest, “Chen” instructed me to download the mobile application from the bogus website, rather than the official Google Play, Apple App Store, or Microsoft Store. The download process for Android and Windows involved retrieving simple applications (APK and installation .EXE, respectively). In contrast, the iOS application utilized the 2021 .

The Windows application, a pirated iteration of the MetaTrader 4 desktop app, was already flagged in our detection system. (Although a revised version wasn’t, we have now incorporated it.) This app possesses a valid signature (although issued by a Russian authority), but its connectivity information was tampered with to include a malevolent server in its list. The same applied to the Android and iOS counterparts—on the outside, both were genuine applications signed by the developer, but with altered connection details. Due to MetaTrader 4’s query language, it was feasible to essentially construct new applications on top of the existing ones.

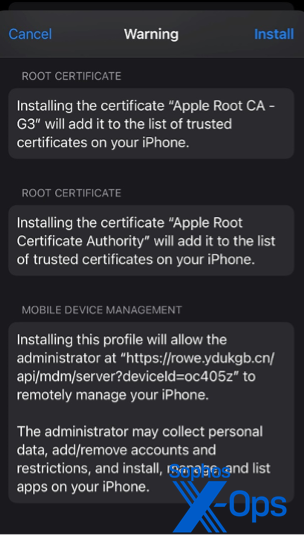

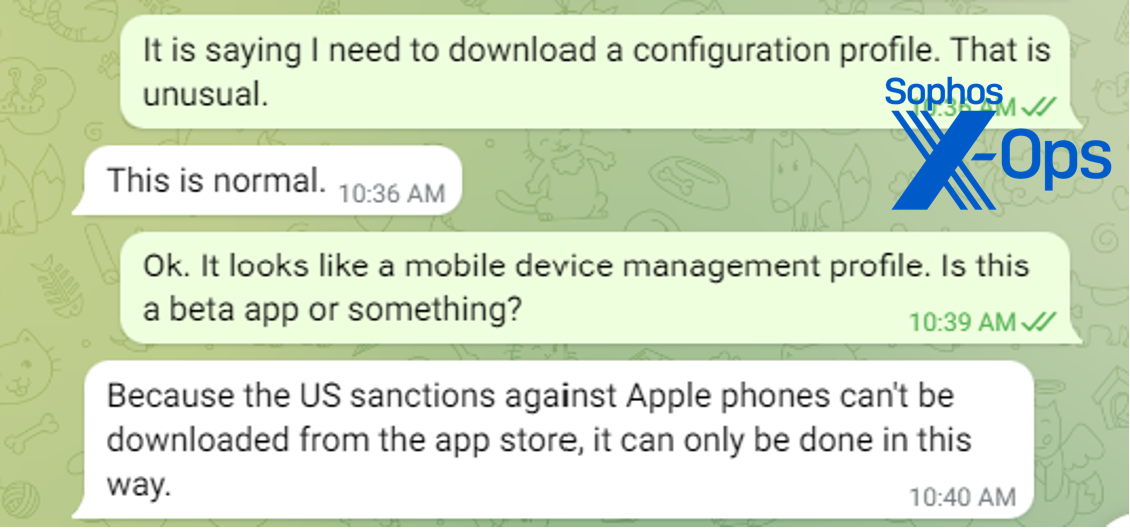

Downloading the Windows and Android applications proved to be straightforward. However, the iOS setup required consenting to an enterprise mobile management profile linking my (testing) device to a server in China—a major warning sign, yet one that many users could overlook due to social engineering tactics.

Curious as to why I had to utilize this unconventional app installation method, I was informed it was due to “US sanctions”:

Essentially, this claim was partly accurate—MetaTrader 4 is crafted by a Russian software firm and isn’t accessible on the US Apple App Store. The version procured from the counterfeit site was minimally altered to include a list of backend servers pointing to those controlled by the scammers. The absence of the legitimate app on the iOS store benefited the scammers, as the victim had no means to download an authentic version conveniently.

Before proceeding with the iOS app download, I initiated a packet capture to monitor the traffic. A detailed list of domains and IP addresses linked to the illicit application infrastructure is included in the IoC document referenced at the conclusion of this report. Most of the components were hosted on Binfang and Alibaba servers, accompanied by some content delivered via Cloudflare; certain certificates were staged utilizing Akamai.

The scammers guided me through the installation process, providing screenshots with highlighted areas for me to tap. I was directed to locate the appropriate server name in the configuration (mirroring the financial entity the scammers were masquerading as):

After selecting the correct server, I was then led through setting up a “practice” account with a balance of $100,000. Upon completion, the app showcased a live market tracking screen originating from another server located in Hong Kong.

Post several tutorials on how to establish deals, identify profit-taking thresholds, and loss boundaries—each of which the deceiver walked me through using screenshots that matched our conversation time— the deceiver suggested introducing me to her “kin” to help me with setting up a genuine account and obtaining trading suggestions.

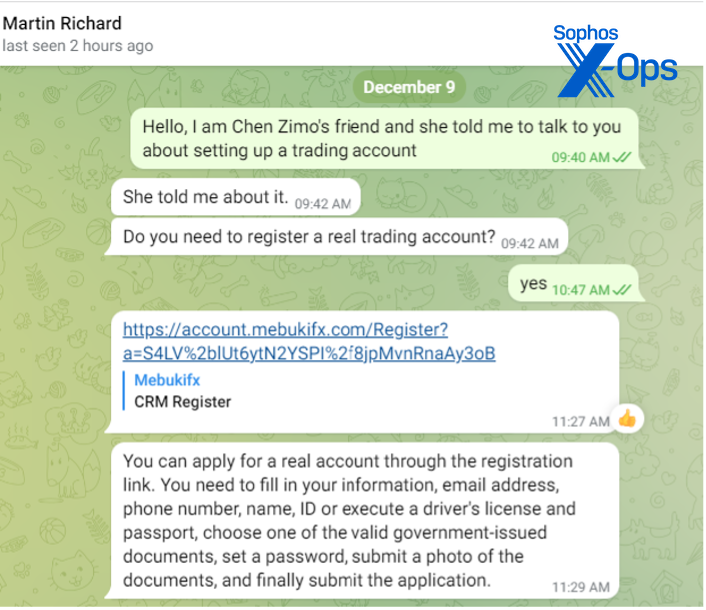

“Martin Richard,” the supposed uncle, had an impressive (fabricated) background—the deceiver asserted “he” was a former analyst at Goldman Sachs.

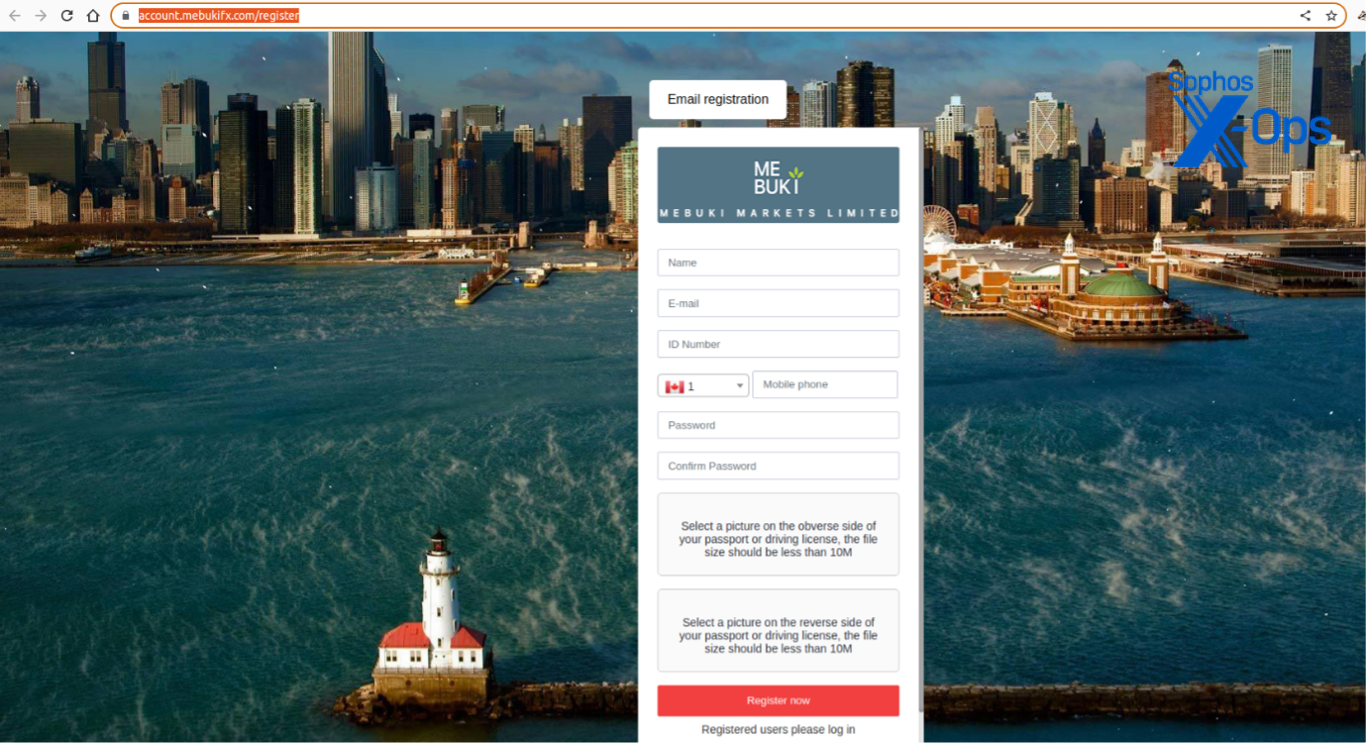

“Martin Richard” instructed me to register an account through another deceitful host page. It replicated a Know-Your-Customer style registration, asking for photos of government ID. The site also displayed animated snow in the background, and an image of downtown Chicago (noticeable by the Navy Pier and several other landmarks):

Once a “valid” account was arranged, “Martin” mentioned, I could deposit funds and commence trades under his guidance.

The Telegram account under “Martin,” unlike the account under “Chen,” utilized a US number registered via Peerless Network, another VoiP provider.

Ridding the Issue

The scam operation commenced in October, with most technical information gathering happening in November. We exchanged information about this actor with Japan CERT (due to the brand appropriation related to a Japanese financial institution), Apple, Google, and others. We informed Apple regarding the initial enterprise app distribution “team” and categorized the domains as malware hosts in our reputation database.

However, as these measures took effect, the scam shifted to new domains. I informed the scammers that I faced issues downloading the app to work, and they promptly steered me towards the new download infrastructure (using the domain mebukifx[.]com) and new enterprise mobile provisioning profile.

As highlighted by Jagadeesh Chandraiah in previous studies of such schemes, the exploitation of the iOS enterprise application distribution system seems to be facilitated through a third-party service for iOS developers. Ad hoc application distribution isn’t particularly uncommon in many regions due to the constraints of the official Apple Store, especially to comply with Chinese government regulations. Once the developer licenses connected to a service like this are revoked, the service providers swiftly establish a new one, or their developers shift to a different distributor.

Evaluating the Swindlers

This specific scam operation didn’t possess the same finesse as some others I’ve encountered in terms of social manipulation. Attempts to build rapport were limited to a few images and a video sent to establish the false persona. At one instance, the “uncle” began responding in Chinese to English inquiries. Nevertheless, the technical complexities of the websites and mobile apps could have been sufficient to convince some individuals to transfer funds into their fraudulent exchange, particularly with communication in other languages potentially appearing more convincing.

Contrastingly, in the upcoming scenario I’ll discuss—a ring in Cambodia running multiple crypto trading scams—there was a more elaborate backstory with increased direct interaction. The scammers used a mix of flirtation, shared interests, and voice and video calls on the messaging app to reinforce trust. (For instance, upon learning about my cat, their representative suddenly had a cat too.) While the Hong Kong-based ring had minimal interaction due to time zone differences, the Cambodian scammers operated on North American hours and messaged multiple times daily.

Given the fluidity of the technical aspects in such scams, public awareness of their operational methods is the only reliable defense against them. What might have been an obvious scam to me may not have been discernible to many educated individuals in vulnerable situations—considering how the COVID 19 pandemic and its aftermath have impacted numerous people, creating a significant pool of potential victims. These scams will undoubtedly become more sophisticated with time. This scam’s emphasis on gold—something many individuals may trust more than cryptocurrencies—illustrates how these scams will continuously identify exploitable niches.

You can find signs of compromise related to this scam on the SophosLabs Github page here.