In August 2022, Sophos X-Ops released a white paper discussing multiple attackers – wherein, opponents target the same entities repeatedly. A pivotal suggestion made in that study was to prioritize fixing severe or well-known vulnerabilities that might impact users’ specific software setups. While we believe this is still valuable counsel, prioritization presents a complicated challenge. How can you distinguish the most critical vulnerabilities? And how can you effectively schedule remediation, given that resources remain constant but the annual count of published CVEs keeps rising, from 18,325 in 2020 to 25,277 in 2022 and further to 29,065 in 2023? According to a recent study, the mean remediation capacity across organizations is 15% of open vulnerabilities on a monthly basis.

An established method is to prioritize updates based on severity (or by risk, a differentiation we will elaborate on later) using CVSS ratings. The FIRST’s Common Vulnerabilities Scoring System has been in existence for an extensive period, offering a numerical assessment of vulnerability gravity ranging from 0.0 to 10.0. It is widely adopted for prioritization and obligatory in certain sectors and governmental bodies, like the Payment Card Industry (PCI) and portions of the US federal government.

Regarding its functionality, it is seemingly simple. Input details about a vulnerability, and you receive a score indicating if the bug is Low, Medium, High, or Critical. Consequently, you filter out irrelevant bugs, focus on fixing Critical and High vulnerabilities from the remaining bunch, and address Mediums and Lows later or assume the risk. The entire process is consolidated on a 0-10 scale, making it theoretically straightforward.

Nonetheless, there is more depth to this than meets the eye. In this piece, the initial of a two-segment series, we will delve into the intricacies of CVSS and outline why solely relying on it for prioritization may not be comprehensive. In the subsequent segment, we will explore alternative approaches that could offer a holistic view of risk for better prioritization.

Before delving further, a critical point to note. While we will discuss some limitations of CVSS in this feature, it is important to acknowledge that formulating and maintaining such a framework is laborious and somewhat underappreciated. CVSS is subject to significant scrutiny, some related to inherent flaws in the concept and others concerning how organizations implement the framework. It is essential to emphasize that CVSS is not a proprietary, subscription-based tool. It is made freely available for organizations to utilize at their discretion, intending to furnish a practical and valuable reference for evaluating vulnerability seriousness, thereby aiding organizations in enhancing their responses to disclosed vulnerabilities. It is continuously evolving, often in response to external input. Our aim in crafting these pieces is not to discredit the CVSS initiative or its creators and overseers; rather, it is to add context and recommendations around CVSS and its applications, particularly in the realm of remediation prioritization, contributing to broader conversations on vulnerability control.

CVSS is described as “a method to encapsulate the fundamental attributes of a vulnerability and generate a numerical score representing its gravity,” as per FIRST. This numerical rating, as previously mentioned, ranges from 0.0 to 10.0, offering a total of 101 probable values; this can subsequently be translated into a qualitative gauge utilizing the subsequent scale:

- None: 0.0

- Low: 0.1 – 3.9

- Medium: 4.0 – 6.9

- High: 7.0 – 8.9

- Critical: 9.0 – 10.0

This system has been operational since February 2005, with the release of version 1; v2 was introduced in June 2007, succeeded by v3 in June 2015. v3.1, rolled out in June 2019, encompasses minor revisions from v3, and v4 was made public on October 31, 2023. As CVSS v4 has not yet gained widespread adoption at the time of writing (e.g., the National Vulnerability Database (NVD) and numerous vendors like Microsoft predominantly adhere to v3.1), we will assess both versions in this piece.

CVSS stands as the prevailing standard for representing vulnerability severity. It features on CVE listings in the NVD and across various other vulnerability repositories and channels. The objective is to present a solitary, uniform, platform-agnostic rating.

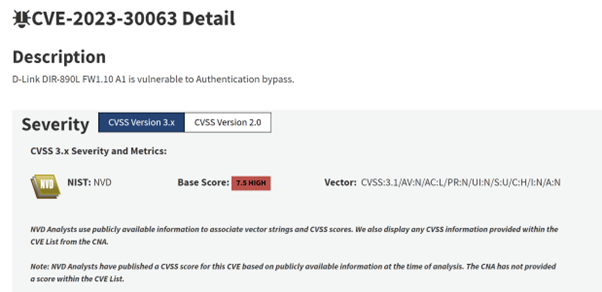

Figure 1: The entry for CVE-2023-30063 on the NVD. Observe the v3.1 Base Score (7.5, High) and the vector string, to be elaborated upon shortly. Also, note that as of March 2024, the NVD does not include CVSS v4 scores

The primary metric most providers focus on is the Base Score, reflecting a vulnerability’s inherent attributes and probable impacts. The process of computing a score involves evaluating a vulnerability through two subcategories, each with its unique set of vectors contributing to the overall assessment.

The initial subcategory pertains to Exploitability, which comprises the following vectors (potential values enclosed in brackets) in CVSS v4:

- Attack Vector (Network, Adjacent, Local, Physical)

- Attack Complexity (Low, High)

- Attack Requirements (None, Present)

- Privileges Required (None, Low, High)

- User Interaction (None, Passive, Active)

The subsequent category concerns Impact. The vectors below each have three possible values (High, Low, and None):

- Vulnerable System Confidentiality

- Subsequent System Confidentiality

- Vulnerable System Integrity

- Subsequent System Integrity

- Vulnerable System Availability

- Subsequent System Availability

So, how does one arrive at an actual figure after inputting these values? In v3.1, as detailed in FIRST’s CVSS specification document, the metrics (slightly varying from the v4 metrics aforementioned) are linked to a numerical value.

Figure 2: A section from FIRST’s CVSS v3.1 documentation, illustrating the numerical values of various parameters

To determine the v3.1 Base estimation, we initially compute three secondary estimations: an Impact Sub-Estimation (ISE), an Impact Value (which utilizes the ISE), and an Exploitability Value.

Impact Sub-Estimation

1 – [(1 – Confidentiality) * (1 – Integrity) * (1 – Availability)]

Impact Value

- If the extent remains the same, 42 * ISE

- If the extent changes, 52 * (ISE – 0.029) – 3.25 * (ISE – 0.02)15

Exploitability Value

8.22 * AttackVector * AttackComplexity * PrivilegesRequired * UserInteraction

Base Value

Assuming the Impact Value surpasses 0:

- If the extent remains unchanged: (Roundup (Minimum [(Impact + Exploitability), 10])

- If the extent changes: Roundup (Minimum [1.08 * (Impact + Exploitability), 10])

In this context, the formula employs two custom operations, Roundup and Minimum. Roundup “displays the smallest number, specified to one decimal place, that is equal to or higher than its input,” and Minimum “displays the smaller of its two arguments.”

Considering that CVSS is an open-source specification, we can manually analyze an example using the v3.1 vector string for CVE-2023-30063, as displayed in Figure 1:

CVSS:3.1/AV:N/AC:L/PR:N/UI:N/S:U/C:H/I:N/A:N

We will reference the vector outcomes and their corresponding numerical values to determine what figures to input into the formulas:

- Attack Vector = Network = 0.85

- Attack Complexity = Low = 0.77

- Privileges Required = None = 0.85

- User Interaction = None = 0.85

- Extent = Unchanged (no designated value in itself; instead, Scope can tweak other vectors)

- Confidentiality = High = 0.56

- Integrity = None = 0

- Availability = None = 0

Initially, we compute the ISE:

1 – [(1 – 0.56) * (1 – 0) * (1 – 0] = 0.56

Since the Extent remains unchanged, for the Impact value we multiply the ISE by 6.42, yielding 3.595.

The Exploitability value is 8.22 * 0.85 * 0.77 * 0.85 * 0.85, which results in 3.887.

Lastly, we incorporate these values into the Base Value formula, which essentially combines these two values, resulting in 7.482. Rounded to one decimal place, this equates to 7.5, as per the CVSS v3.1 rating on NVD, indicating that this vulnerability is classified as High severity.

v4 adopts a distinct strategy. Amidst other alterations, the Extent metric has been eliminated; a new Base metric (Attack Requirements) exists; and the User Interaction now offers more detailed options. However, the most significant modification is the rating system. Presently, the computation method no longer hinges on ‘imprecise values’ or a formula. Alternatively, ‘equivalence sets’ of various value combinations have been organized by experts, condensed, and inserted into bins representing ratings. While calculating a CVSS v4 rating, the vector is computed, and the associated rating is returned, utilizing a lookup table. Hence, for instance, a vector of 202001 corresponds to a rating of 6.4 (Medium).

Irrespective of the calculation method, the Base Value is not intended to evolve over time, as it relies on characteristics unique to the vulnerability. Nevertheless, the v4 specification also encompasses three other metric categories: Threat (varying features of a vulnerability); Environmental (unique features pertaining to a user’s setting); and Supplemental (additional external attributes).

The Threat Metric Group solely includes one metric (Exploit Maturity); this supersedes the Temporal Metric Group from v3.1, which encompassed metrics for Exploit Code Maturity, Remediation Level, and Report Confidence. The Exploit Maturity metric aims to reflect the probability of exploitation and offers four potential statuses:

- Not Defined

- Attacked

- Proof-of-Concept

- Unreported

While the Threat Metric Group aims to add extra context to a Base rating based on threat intelligence, the Environmental Metric Group is a variant of the Base rating, enabling an organization to adjust the rating “based on an asset’s significance to a user’s organization.” This metric includes three sub-divisions (Confidentiality Requirement, Integrity Requirement, and Availability Requirement), alongside the altered Base metrics. The values and definitions remain consistent with the Base metrics, but the revised metrics enable users to depict mitigations and settings that may heighten or diminish severity. For example, a default configuration of a software component might lack authentication implementation, resulting in a Base metric of None for the Privileges Required metric. Nevertheless, an organization could have safeguarded that component with a password in their environment, thereby classifying the Modified Privileges Required as either Low or High, and consequently reducing the Environmental rating for that organization compared to the Base rating.

Lastly, the Supplemental Metric Group includes the following non-mandatory metrics, which do not influence the rating:

- Automatable

- Recovery

- Safety

- Value Density

- Vulnerability Response Effort

- Provider Urgency

The extent of utilization of the Threat and Supplemental Metric Groups in v4 remains to be seen. With v3.1, Temporal metrics are seldom evident in vulnerability databases and feeds, and Environmental metrics are deemed for per-infrastructure use, leaving the extent of their adoption uncertain.

Notwithstanding, Base ratings are widespread, and on a superficial level, the rationale behind this is apparent. Despite the alterations in v4, the fundamental essence of the outcome – a value between 0.0 and 10.0, supposedly reflecting a vulnerability’s severity – remains unchanged.

Nonetheless, the system has encountered scrutiny.

What is the implication of a CVSS rating?

This is not an inherent issue of the CVSS specification, but there might be confusion regarding what a CVSS rating actually signifies, and its intended application. As Howland highlights, the documentation for CVSS v2 explicitly states that the framework’s function is risk management:

“Currently, IT management must identify and assess vulnerabilities across many disparate hardware and software platforms. They need to prioritize these vulnerabilities and remediate those that pose the greatest risk. But when there are so many to fix, with each being scored using different scales, how can IT managers convert this mountain of vulnerability data into actionable information? The Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) is an open framework that addresses this issue.”

In the v2 specification, the word ‘risk’ appears 21 times, while ‘severity’ is mentioned only thrice. By the v4 specification, these frequencies have essentially flipped; ‘risk’ is noted three times, whereas ‘severity’ appears 41 times. The opening sentence of the v4 specificationcountries affirm that the intent of the framework is to “expressing the qualities and seriousness of software vulnerabilities.” Therefore, over time, the specified goal of CVSS has shifted, transitioning from a gauge of peril to a gauge of seriousness.

That’s not a ‘aha’ in any manner; the writers might have merely chosen to elucidate exactly what CVSS is meant for, to prevent or resolve misunderstandings. The genuine quandary here does not rest in the framework itself, but in the manner it is at times executed. Despite the clarifications in recent standards, CVSS scores may still occasionally be (mis)used as a gauge of risk (e.g., “the combination of the probability of an event and its consequences,” or, based on the frequently referenced formula, Threat * Vulnerability * Consequence), but they do not genuinely quantify risk in any way. They measure one facet of risk, presuming that an attacker “has already located and identified the vulnerability,” and in gauging the attributes and potential impact of that vulnerability if an exploit is created, and if that exploit is effective, and if the plausible worst-case scenario unfolds as a result.

A CVSS score can be a segment of the puzzle, but by no means the finalized jigsaw. While it might be convenient to have a solitary number on which to ground decisions, risk is a significantly more intricate challenge.

Nonetheless, can I still utilize it for ordering, isn’t that so?

Yes and no. Despite the escalating figures of published CVEs (and it’s valuable to stress that not all vulnerabilities receive CVE IDs, so that’s not a finalized jigsaw either), just a fraction – between 2% and 5% – are ever identified as being exploited in-the-wild, as per research. Consequently, if a vulnerability intelligence feed conveys that 2,000 CVEs have been disclosed this month, and 1,000 of them impact assets in your establishment, only about 20-50 of those will probably be exploited (that we’ll know about).

That’s the positive news. Yet, disregarding any exploitation that transpires prior to a CVE’s disclosure, we are unaware which CVEs threat actors will exploit in the coming days, or when – so how can we determine which vulnerabilities to patch initially? One could deduce that threat actors utilize a similar mental process to CVSS, albeit less formalized, to craft, market, and utilize exploits: focusing on high-impact vulnerabilities with low complexity. In that scenario, prioritizing high CVSS scores for rectification is rational.

However, researchers have demonstrated that CVSS (at least, until v3) is an undependable forecaster of exploitability. In 2014, researchers at the University of Trento contended that “fixing a vulnerability just because it was assigned a high CVSS score is equivalent to randomly picking vulnerabilities to fix,” based on an analysis of publicly accessible data on vulnerabilities and exploits. More recently (March 2023), Howland’s research on CVSS reveals that bugs with a CVSS v3 score of 7 are the most probable to be weaponized, in a sample of over 28,000 vulnerabilities. Vulnerabilities with scores of 5 were more inclined to be weaponized than those with scores of 6, and 10-rated vulnerabilities – Critical flaws – were less probable to have exploits developed for them than vulnerabilities ranked as 9 or 8.

In other terms, there doesn’t seem to be a connection between CVSS score and the probability of exploitation, and, according to Howland, that’s still the situation even if we emphasize pertinent vectors – like Attack Complexity or Attack Vector – more significantly (although it remains to be observed if this will still be valid with CVSS v4).

This is a counterintuitive conclusion. As the authors of the Exploit Prediction Scoring System (EPSS) mention (more on EPSS in our forthcoming article), after depicting CVSS scores against EPSS scores and identifying less correlation than expected:

“this…provides suggestive evidence that attackers are not only targeting vulnerabilities that produce the greatest impact, or are necessarily easier to exploit (such as for example, an unauthenticated remote code execution).”

There are several explanations why the notion that attackers are most keen on exploiting exploits for severe, low-effort vulnerabilities doesn’t stand. Just like risk, the criminal ecosystem can’t be condensed to a single facet. Other factors which might influence the likelihood of weaponization involve the install base of the impacted product; prioritizing specific impacts or product families over others; variances by crime type and motivation; geography, and so on. This is a convoluted, and distinct, discussion, and beyond the scope for this article – nevertheless, as Jacques Chester contends in a meticulous and thought-provoking blog entry on CVSS, the principal takeaway is: “Attackers do not appear to use CVSSv3.1 to prioritize their efforts. Why should defenders?” Nevertheless, Chester doesn’t go to the extent of arguing that CVSS should not be employed at all. However, it possibly shouldn’t be the singular factor in prioritization.

Replicability

One of the touchstone evaluations for a scoring framework is that, with the same information, two individuals ought to be able to work through the process and end up with roughly the same score. In a field as intricate as vulnerability management, where subjectivity, interpretation, and technical comprehension frequently come into play, we might sensibly envision a degree of deviation – but a 2018 analysis demonstrated noteworthy discrepancies in evaluating the gravity of vulnerabilities using CVSS metrics, even among security professionals, which might culminate in a vulnerability being ultimately categorized as High by one analyst and Critical or Medium by another.

Nonetheless, as FIRST emphasizes in its specification document, its aim is that CVSS Base scores should be computed by vendors or vulnerability analysts. In reality, Base scores typically manifest on public feeds or databases which organizations then incorporate – they’re not intended to be recalibrated by numerous individual analysts. That’s comforting, albeit the fact that seasoned security professionals made, at least in some instances, quite diverse assessments could be a cause for concern. It’s ambiguous whether that was a result of ambiguity in CVSS definitions, or a lack of CVSS scoring experience among the study’s participants, or a wider issue pertaining to divergent understanding of security concepts, or some or all of the above. Added research is possibly called for on this point, and on the degree to which this issue still applies in 2024, and to CVSS v4.

Detriment

CVSS v3.1’s impact metrics are restrained to those linked with traditional vulnerabilities in traditional environments: the familiar CIA triad. What v3.1 does not consider are newer advancements in security, where attacks against systems, devices, and infrastructure can cause consequential physical detriment to individuals and property.

Nevertheless, v4 does tackle this predicament. It includes a dedicated Safety metric, with the following potential values:

- NotListed as follows:

- Characterized

- Existing

- Insignificant

When it comes to the latter two values, the framework makes use of the IEC 61508 standard interpretations of “insignificant” (minor injuries at most), “marginal” (major injuries to one or more individuals), “critical” (loss of a single life), or “catastrophic” (multiple loss of life). The Safety metric can also be employed to the altered Base metrics within the Environmental Metric Group, for the Subsequent System Impact set.

The importance of context

CVSS strives to maintain simplicity as much as possible, sometimes leading to a reduction in complexity. For example, in v4, consider Attack Complexity; the only available values are Low and High.

Low: “The attacker must make no identifiable effort to exploit the vulnerability. Target-specific circumvention is unnecessary for exploitation. An attacker can anticipate consistent success against the vulnerable system.”

High: “The success of the attack relies on evading or bypassing security enhancements in place that would typically impede the attack […].”

While some threat actors, vulnerability analysts, and vendors may dispute the idea that a vulnerability is simply categorized as being of ‘low’ or ‘high’ complexity, members of the FIRST Special Interest Group (SIG) argue that v4 has addressed this with the new Attack Requirements metric, which introduces more detail by capturing the conditions required for exploitation.

User Interaction is another instance. While v4 offers more detailed choices for this metric compared to v3.1 (which only has None or Required), the differentiation between Passive (restricted and involuntary interaction) and Active (defined and intentional interaction) might not fully encompass the various social engineering techniques prevalent in real-world scenarios, not to mention the complexities introduced by security measures. For example, convincing a user to open a document (or just preview it in the Preview Pane) is usually easier than convincing them to open a document, then disable Protected View, and then disregard a security warning.

Granted, CVSS must balance between being excessively detailed (including numerous potential values and variables that would elongate the scoring process) and overly simplistic. Adding more granularity to the CVSS model would complicate what is meant to be a quick, practical, one-size-fits-all severity guide. However, it is evident that crucial nuances may be overlooked – and the vulnerability landscape is often nuanced by nature.

Some definitions in both the v3.1 and v4 specifications may also cause confusion for certain users. For example, consider the scenario provided under the Attack Vector (Local) definition:

“the attacker exploits the vulnerability by gaining access to the target system locally (e.g., keyboard, console), or via terminal emulation (e.g., SSH)” [emphasis added; in the v3.1 specification, this is “or remotely (e.g., SSH)”]

It should be noted that the use of SSH here appears to differ from accessing a host on a local network via SSH, as per the Adjacent definition:

“This could imply an attack being initiated from the same shared proximity (e.g., Bluetooth, NFC, or IEEE 802.11) or logical (such as local IP subnet) network, or from within a secure or otherwise restricted administrative domain…” [emphasis added]

While the specification does distinguish whether a vulnerable component is “bound to the network stack” (Network) or not (Local), this distinction might be counterintuitive or perplexing for some users, either during CVSS score calculations or in interpreting a vector string. These definitions are not necessarily incorrect, but they may appear opaque and unintuitive to some users.

Lastly, Howland presents a practical case study where they believe CVSS scores fail to consider context. CVE-2014-3566 (the POODLE vulnerability) received a CVSS v3 score of 3.4 (Low). However, it impacted nearly a million websites at the time of disclosure, causing considerable alarm and affecting organizations differently – a factor which, according to Howland, CVSS fails to take into account. There is also another context-related issue – beyond the scope of this series – regarding whether media coverage and hype about a vulnerability unduly influence prioritization. Conversely, certain researchers assert that vulnerability rankings might be inflated due to not always factoring in context, when the actual real-world risk is relatively low.

‘We’re all just ordinal beings…’

In v3.1, CVSS uses ordinal data at times as input for equations. Ordinal data is ranked data with no defined distances between items (e.g., None, Low, High), and as highlighted by researchers from Carnegie Mellon University, it is illogical to add or multiply items of ordinal data. For instance, in a survey using a Likert scale, multiplying or adding the responses holds no significance. To illustrate with a non-CVSS example, answering Happy [4.0] to a salary query and Somewhat Happy [2.5] to a work-life balance question does not equate to being able to multiply those to conclude an overall score of 10.0 [‘Very happy with my job’].

The presence of ordinal data also implies that averaging CVSS scores is inappropriate. For instance, if an athlete secures a gold medal in one event and a bronze medal in another, stating that on average they achieved silver would not be sensible.

In v3.1, it remains unclear how the hardcoded numerical values for the metrics were chosen, which might be one reason for FIRST opting to abandon a formula in v4. Instead, v4’s scoring method relies on categorizing and ranking different value combinations, computing a vector, and utilizing a lookup function to assign a score. Thus, rather than employing a formula, experts selected by FIRST have assessed the severity of various vector combinations during a consultation period. This approach seems logical on the surface, circumventing formula-related issues altogether.

An enigmatic system?

While the specifications, equations, and definitions for v3.1 and v4 are publicly accessible, some researchers argue that CVSS lacks transparency. In v4, for instance, instead of inputting numbers into a formula, analysts can now reference a vector from a pre-established list. However, the transparency of this process is not evident.

The process of selecting these experts, comparing the “vectors representing each equivalent set,” or utilizing the “expert comparison data” to determine the order of vectors from least severe to most severe has not been publicly disclosed as far as our knowledge goes. This lack of transparency regarding selection criteria and methodology is not exclusive to CVSS, as we will delve deeper into in Part 2 of this series.

When it comes to security matters, results generated by systems with undisclosed mechanics should be viewed with a level of skepticism proportional to the significance and implications of their use. This cautious approach is crucial given the potential risks associated with relying on potentially inaccurate or misleading results.

Putting a Lid on It

It might be worth pondering why CVSS scores adhere to a scale of 0 to 10. The apparent rationale behind this choice is to provide a straightforward and easily comprehensible scale. However, this range is essentially arbitrary, especially considering that the inputs to the equations are qualitative and CVSS is not a measure of probability. In version 3.1, the Minimum function ensures that scores are capped at 10. Otherwise, it could theoretically exceed 10.73 according to our calculations. In version 4, the scoring mechanism deliberately restricts scores to a maximum of 10 as it represents the highest category.

Is there a maximum threshold for the severity of a vulnerability? Are all vulnerabilities that score 10.0 equally critical? Presumably, the decision to limit scores at 10 was made for the sake of readability, but does it compromise the accuracy and realism of severity representation?

Consider a hypothetical scenario to illustrate this point: picture a rating system designed to gauge the severity of biological viruses. These scores could provide insights into the potential effects of a virus on individuals, offering some indication of the threat level based on specific characteristics. However, these scores fail to account for individual factors such as age, health status, immune system efficacy, previous immunity, and so forth. They neglect crucial aspects like replication rate, mutational capability, geographic spread, and the availability of preventive measures. Consequently, some scores may seem logical (e.g., ranking HIV higher than a common cold virus), while others appear misleading (e.g., poliovirus scoring high despite its near eradication in most regions). Independent studies have revealed that these scores are ineffective in predicting mortality rates.

Therefore, relying solely on this system for personal risk assessments, such as deciding on social gatherings, travel plans, or healthcare visits, may be questionable. While the system serves a purpose in categorization and highlighting potential threats based on a virus’s inherent traits, it should be complemented with additional information for a comprehensive risk evaluation. It is beneficial to consider these scores in conjunction with other data, despite their limitations.

FIRST emphasizes this aspect in its FAQ for v4. Exploring alternative scoring systems can enhance vulnerability response prioritization and decision-making. In the upcoming article, we will delve into some of these alternatives.