Observation on Staying Authentic: Sophos and the 2024 MITRE ATT&CK Assessments: Corporate by MarcusA

Annually, numerous security service providers – such as Sophos – enlist for MITRE’s ATT&CK Evaluations: Corporate, a comprehensive cyber attack simulation portraying one or more situations inspired by real-world threat actors and their strategies, tools, and processes.

The evaluation is crafted to deliver an authentic (and transparent – the outcomes are publicly accessible) evaluation of security solutions’ efficiencies, based on end-to-end attack sequences encompassing initial infiltration, persistence, lateral movement, and repercussions. Simulations typically incorporate a multi-device ‘client’ environment, comprising endpoints, servers, domain-linked devices, and Active Directory-governed users.

The year 2024 represented the fourth year of Sophos’ participation, and to commemorate this, we desired to offer some perspectives on the content of this year’s assessment and to demonstrate its closeness to reality. Particularly, we will delve into the authenticity of the tools, intricacies in the evaluation methodology, and Sophos’ safeguarding and detection capabilities. Although we cannot cover everything (each scenario consists of 20-40 steps!), we will discuss a range, emphasizing the thoroughness and precision of the simulations.

For the 2024 evaluation, MITRE chose two threat classifications, Data Hostage-Situation Software and the Democratic Republic of Korea (DPRK). The former, as has been customary for a considerable period, poses as one of the most substantial cyber security risks in the sector and keeps evolving, such as the rise in remote crypto locking. The latter is also remarkable, given the escalation of state-backed espionage campaigns linked to the region.

MITRE devised three scenarios centered around these classifications: a strike by a DPRK-associated threat actor concentrating on MacOS (mimicking threat operators engaging MacOS in multiple activities, a trend that appears persistent), and attacks by partners of two ransomware gangs (Cl0p and LockBit).

DPRK

The DPRK scenario was straightforward yet pragmatic, drawing on the sequence of the JumpCloud supply chain compromise: an invader seizes a device, establishes a lasting agent, and filches credentials. It is recognized that actors connected with the DPRK fragment their assaults into distinct stages and maintain hidden routes for subsequent strikes.

Initial Infiltration

Albeit the evaluation implies a supply chain breach, the scenario itself entailed a user fetching and executing a malevolent Ruby script (our study revealed a user-driven path of Ruby). In a practical supply chain assault, pre-loaded software would likely automatically trigger the script. Nevertheless, this remains a feasible and significant tactic – DPRK-linked assaulter will utilize social manipulation to persuade users to implement a script, as current events display.

Just like in the JumpCloud assault, MITRE’s Ruby script (labeled start.rb, thematically corresponding to the genuine script name: init.rb) downloads and executes an inaugural C2 agent (a Mach-O binary), camouflaging itself as a docker-associated component. It’s essential to mention that deciphering authentic JumpCloud samples is infeasible; to our awareness, the genuine samples are not publicly accessible. As with all MITRE ATT&CK Assessments, the malware employed was crafted customarily for the evaluation.

Steadfastness

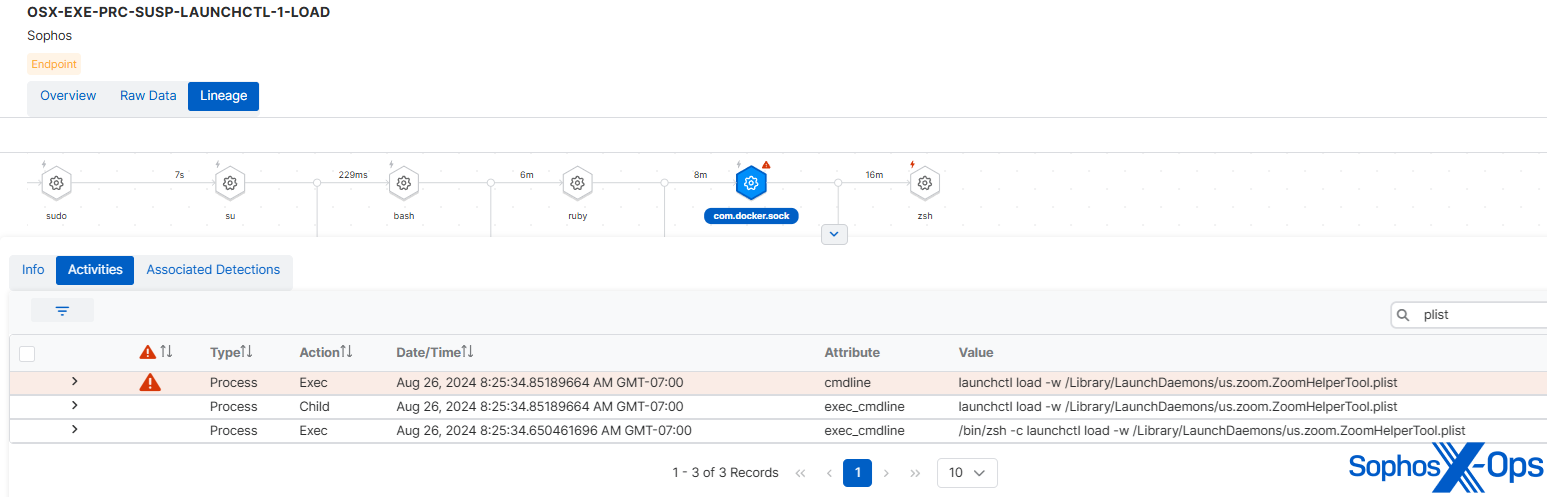

The inaugural C2 agent subsequently downloaded a secondary-stage backdoor (recognized as ‘STRATOFEAR’ in the genuine JumpCloud attack), which established continuity in a similar fashion to the genuine article, through LaunchDaemons (/Library/LaunchDaemons/us.zoom.ZoomHelperTool.plist).

Figure 1: Establishing continuity via ZoomHelperTool.plist

Like the Ruby script in the Initial Infiltration phase, MITRE tailored the backdoor to closely resemble the original. The backdoor

was deposited in the identical spot (/Library/Fonts), bearing a very alike title (the authentic version was referred to as ArialUnicode.ttf.md5, whereas the evaluation version was pingfang.ttf.md5; both ‘Arial’ and ‘pingfang’ are names of authentic fonts).

Similar to the authentic STRATOFEAR, the MITRE backdoor employed encrypted setup files, employing a shell-out openssl enc -d directive and a hardcoded password. Once more, utilizing a direct API-based approach would be more covert, but we are unaware if the JumpCloud assaulter adopted that strategy.

A prompt observation on test security: MITRE employs platforms for C2 that function within the constraints of the test environment, but are not publicly resolvable through DNS. Nonetheless, they are routed to public IP addresses. Consequently, the network traffic mirrors legitimate C2 operations, although the platforms are inaccessible beyond the test environment.

Implications

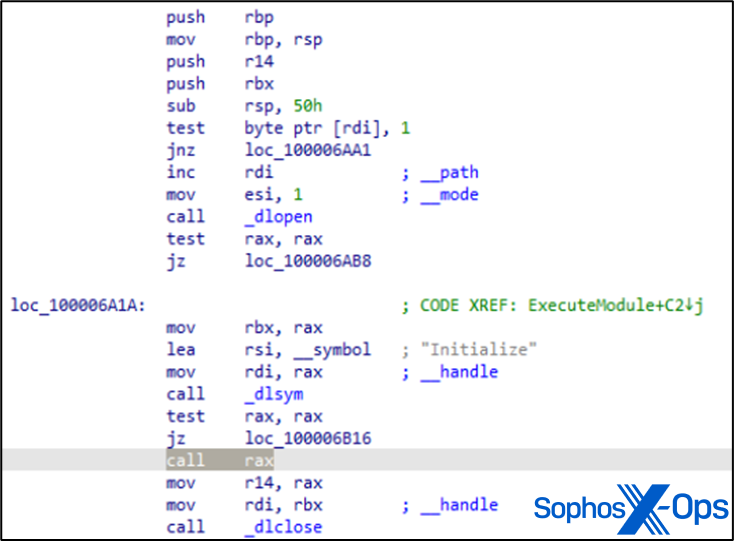

As in the JumpCloud assault, the goal of the assaulter is to amass data, including system details, credentials, and confidential data stored in the Keychain. MITRE’s STRATOFEAR backdoor stayed loyal to the genuine one, as it fetched and executed additional modulesfrom the command and control server to conduct the breach. Similar to the components fetched by authentic STRATOFEAR, these were saved into a .tmp document in the directory of /tmp, each designated with a sequence of six random alphanumeric characters.

In their study, STRATOFEAR by MITRE retrieved /private/tmp/rhkA2f.tmp, a module with the capability to access MacOS keychain files.

Figure 2: Leveraging the ExecuteModule function within MITRE’s STRATOFEAR model, utilizing dlopen/dlsym to trigger an ‘Initialize’ function

The sequence concluded with the malicious access tool gathering the information; the experiment did not entail any real data exfiltration. Although some might view this as a flaw in the approach – as credentials usually only hold value if removed – we would contend that it’s a minor concern. Identifying credential theft as an incident responder allows insight into the potential consequences and the related unauthorized actions.

Cl0p

The following sequence replicated an assault by the Cl0p ransomware faction (also identified as TA505), a well-known threat actor. Here, the attack progression closely resembled – to a large extent – that of an incident from 2019, comprising of a downloader, a persistent Remote Access Trojan (RAT), intricate process injection, and misuse of a trusted process – ultimately culminating in deploying ransomware.

Initial entry

While most of the scenario imitated the 2019 real-world campaign, the initial entry phase differed slightly. Similar to 2019, the menace employed a DLL to plant a lasting RAT. Nevertheless, in contrast to the real-world attack involving malicious Office documents containing an embedded DLL, which was dynamically loaded into the Office process, the MITRE simulation had a user actively run cmd.exe and initiate the DLL via rundll32.exe.

The DLL was already situated on the device, having been fetched through a curl instruction from a separate interactive cmd.exe (this move was not covered in the scenario) following initial entry via RDP. It’s essential to acknowledge that this form of initial entry is very widespread among ransomware alliances and other malevolent actors, particularly in cases of obtaining stolen credentials/access through initial entry brokers (IABs). In a highly noticeable circumstance, Cl0p also exploited a zero-day vulnerability in the MOVEit file transfer application (CVE-2023-34362).

While it’s feasible for an attacker to gain direct remote access to the affected device, the scenario could have potentially integrated the ingress of the DLL tool for a more comprehensive replication.

Endurance

Corresponding to the 2019 campaign, the MITRE ‘threat actor’ integrated the lasting RAT SDBbot by compromising the trusted winlogon.exe process, utilizing Image File Execution Options (IFEO) injection with a ‘VerifierDLL’ key.

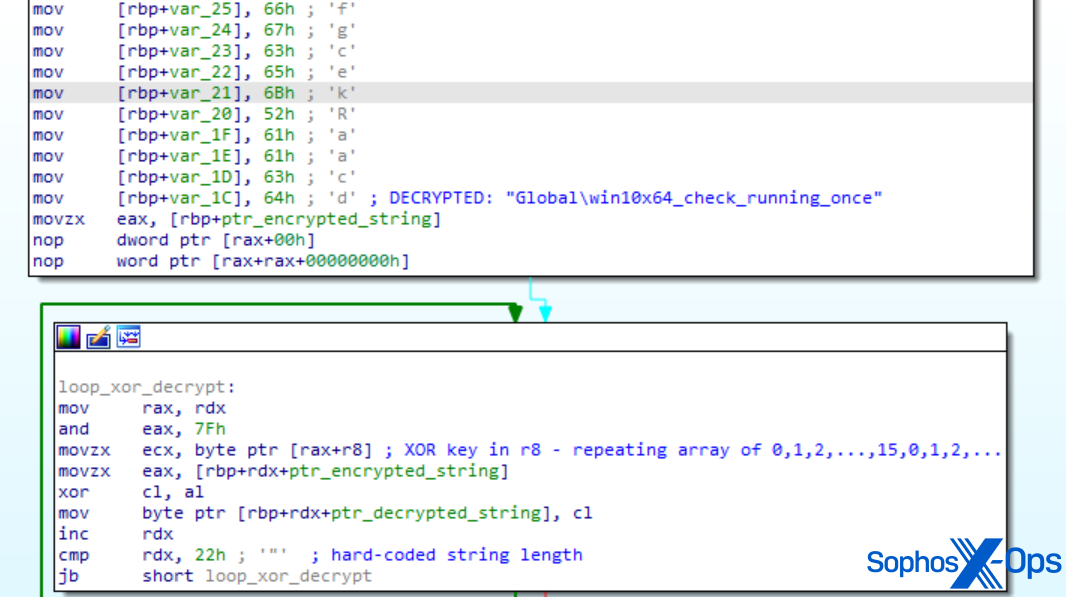

SDBbot employs encrypted strings and a mutex to secure its launch. Analogous to the DPRK scenario, the MITRE model adopted a comparable yet distinct name for the mutex (‘windows_7_windows_10_check_running_once_mutex‘ in the real-world attack, ‘win10x64_check_running_once‘ for the analysis).

Figure 3: Breakdown of MITRE’s SDBbot model. Noting the mutex name and the decryption routine

In MITRE’s rendition of SDBbot, the key content features sixteen escalating bytes from 0 to 15. Although not as robust as a truly random 128-byte sequence, this suffices to veil the strings referencing API names and data fields beyond simplistic static analysis tactics. MITRE executed this strategy of string camouflage across the Cl0p scenario and additionally in the subsequent discussion on the LockBit scenario.

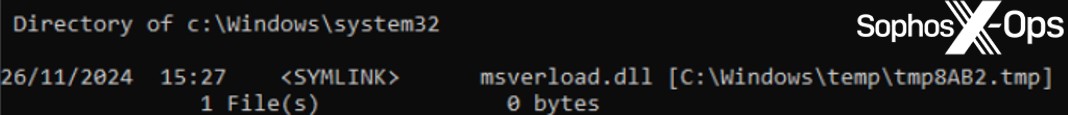

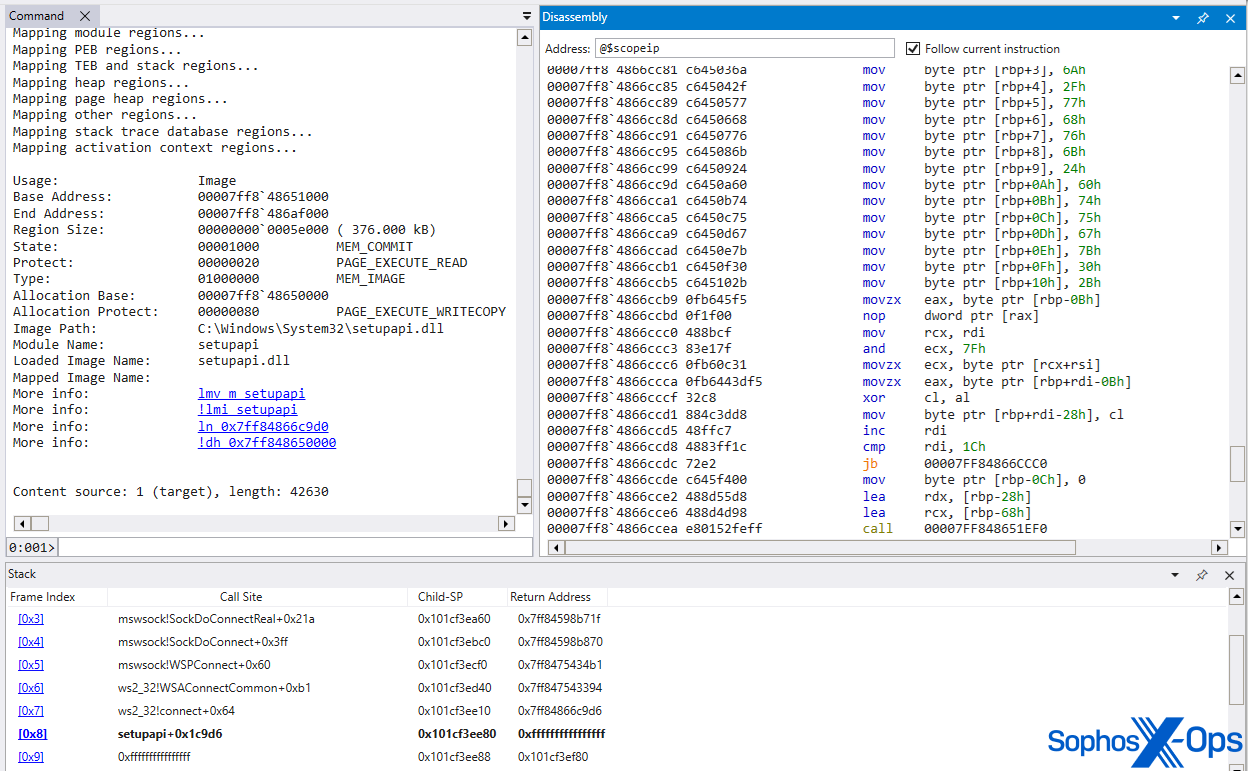

MITRE’s model was introduced via a reflective loader, overwriting image memory in setupapi.dll. As the RAT operates within typical ‘image’ memory, it becomes more challenging to detect compared to if it were within dynamically allocated heap memory. This method of injection is sophisticatedly crafted to circumvent contemporary defenses. MITRE’s method posed another hurdle in detecting the activity of the installer (the rundll32 process) presenting the SDBbot loader component. The installer deposited the loader in a %TEMP% area but established a symbolic link to that pathway within the SYSTEM folder. The IFEO registry key was then aligned to point to the SYSTEM folder path, creating an added layer of abstraction separating the dropper from the persistent RAT.

Figure 4: Illustration of the symbolic link for the msverload.dll loader

The utilization of the ‘VerifierDLLs’ technique introduced added intricacy to the execution path, as the loader (msverload.dll) infiltrated the winlogon.exe process space before its entry point. Subsequently, it deployed VirtualAlloc to infuse and execute embedded shellcode and VirtualProtect to render the otherwise RX image memory of setupapi.dll writable, ahead of replacing its content with the SDBbot RAT. The memory permissions were later reverted to RX,to give the code the appearance of ‘regular’ image storage — resembling how a DLL would show up when directly loaded from the disk.

Figure X: Detection of MITRE’s SDBbot, which is loaded and overwrites the module of the genuine setupapi.dll image storage, with memory protections reset to PAGE_EXECUTE_READ

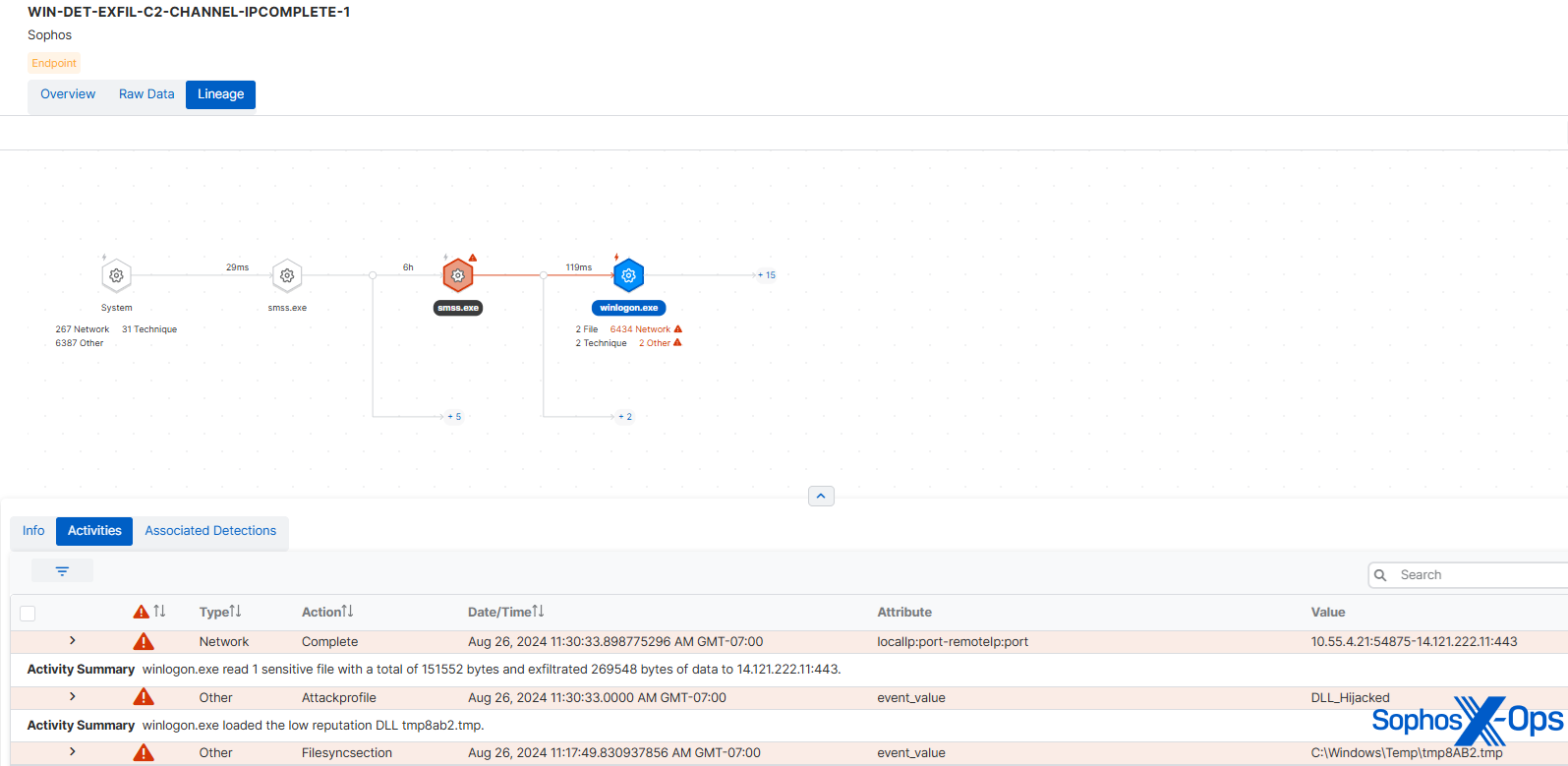

Several aspects were considered in our identification approach here: it raises suspicion having C2 activity originating from a winlogon process, and C2 activity itself serves as a common signal for memory scanning triggers (as elaborated in a blog post on this subject in 2023). Memory scans also found a shellcode pattern. The suspicious C2 event allowed Sophos Detection to capture the data exfiltration behavior, and the exfiltration method – utilizing SDBbot and transmitting data over the C2 channel – was employed by Cl0p in 2020.

Figure 6: Identification of exfiltration during the Cl0p scenario

Effect

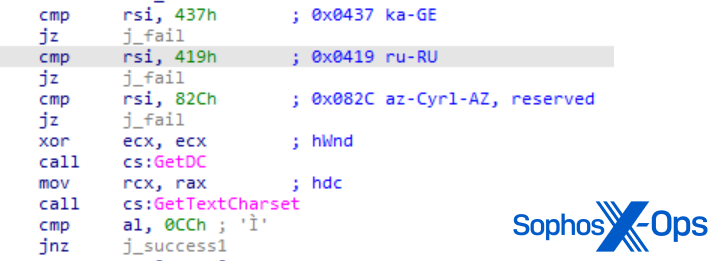

MITRE’s replication of the Cl0p ransomware specimen (sysmonitor.exe, acquired via SBDbot) closely imitated an actual sample from 2019. Similar to the original, MITRE’s specimen employed GetKeyboardLayout to investigate layouts utilized in Russia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan (to avoid targeting systems using them). It similarly used an identical technique for the GetDC/GetTextCharset APIs to achieve the same goal.

Figure 7: MITRE’s Cl0p specimen calling GetDC and GetTextCharset to check for infected hosts in Russia, Georgia, or Azerbaijan

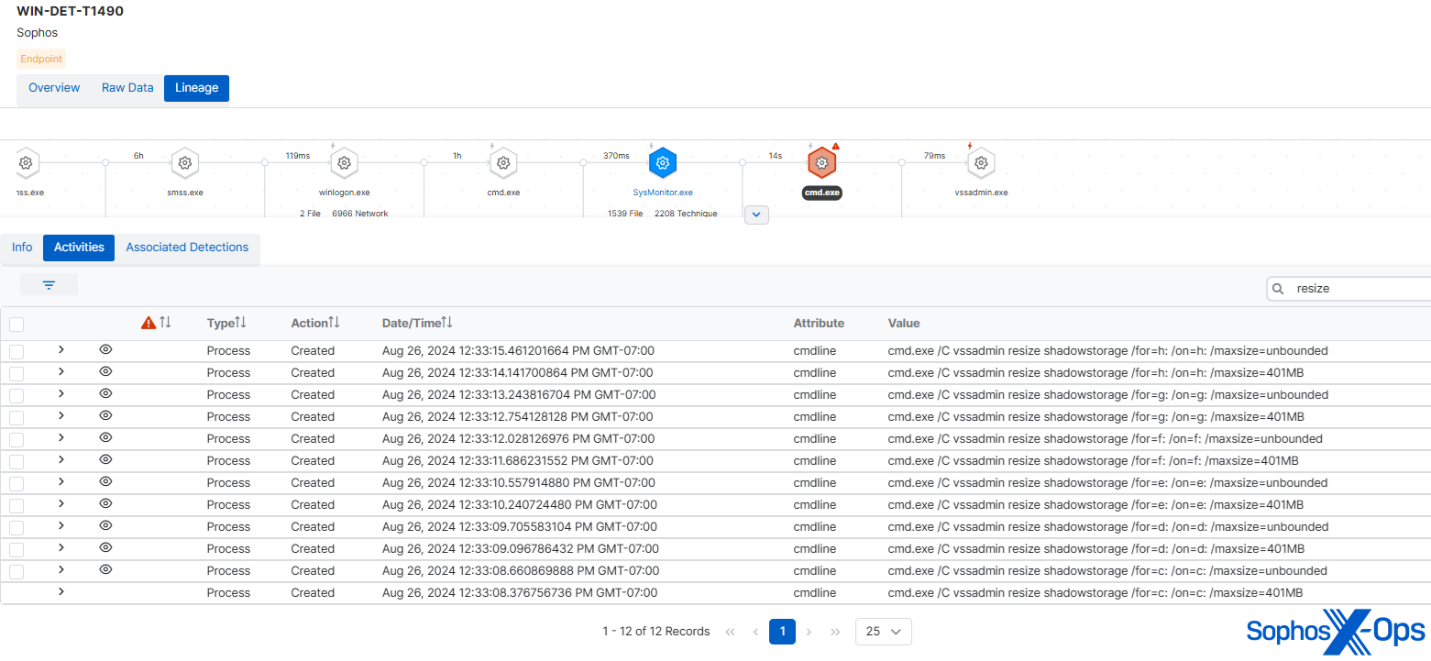

We also observed other almost identical matches in behavior and methodologies, particularly in how the ransomware managed shadow volumes and attempted to halt various services on compromised hosts.

Many ransomware types seek to erase shadow volumes to prevent victims from restoring data, and then resize the shadow storage to hinder the creation of further shadow volumes. However, the 2019 Cl0p ransomware executed the latter step in a specific manner, rotating through a predetermined list of drives (from C to H). MITRE’s specimen reproduced this behavior precisely.

Figure 8: MITRE’s replication of Cl0p cycling through different drives to resize the shadow storage

Furthermore, similar to many ransomware variations,proceed with the deployment of their ransomware. The LockBit scenario by MITRE included Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) commonly utilized by certain LockBit affiliates. In a manner similar to the Cl0p scenario, it is interesting to note that while the behavior of ransomware binaries tends to remain consistent across attacks, affiliates might have varying playbooks, resulting in differences in TTPs and IOCs.

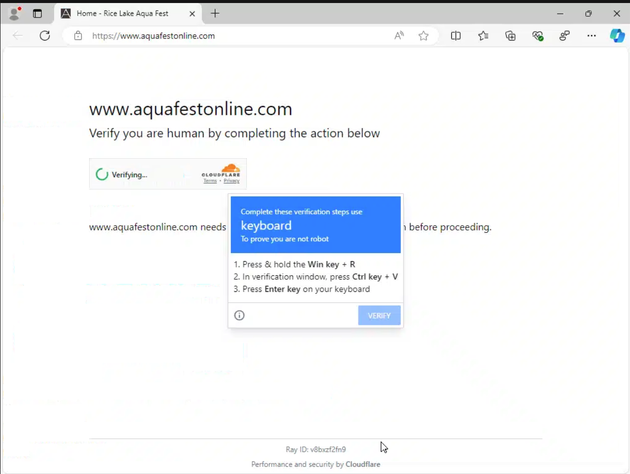

Initial Ingress

The ‘threat actor’ in the MITRE simulation initiated their assault by authenticating through an externally-facing TightVNC service, a legitimate tool for remote administration, using compromised credentials obtained previously. Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) affiliates commonly gain initial access in this manner, leveraging credentials and services that have been purchased on cybercrime forums, as highlighted earlier in the Cl0p scenario.

After gaining access, the attacker conducted various discovery commands, consistent with actions observed early in RaaS attacks, such as:

nltest /dclist:<domain>

cmdkey /list

net group “Domain Admins” /domain

net group “Enterprise Admins” /domain

net localgroup Administrators /domain

powershell /c "get-wmiobject Win32_Service |where-object { $_.PathName -notmatch "C:Windows" -and $_.State -eq "Running"} | select-object name, displayname, state, pathname

These commands closely resembled those detected during a LockBit attack in 2022.

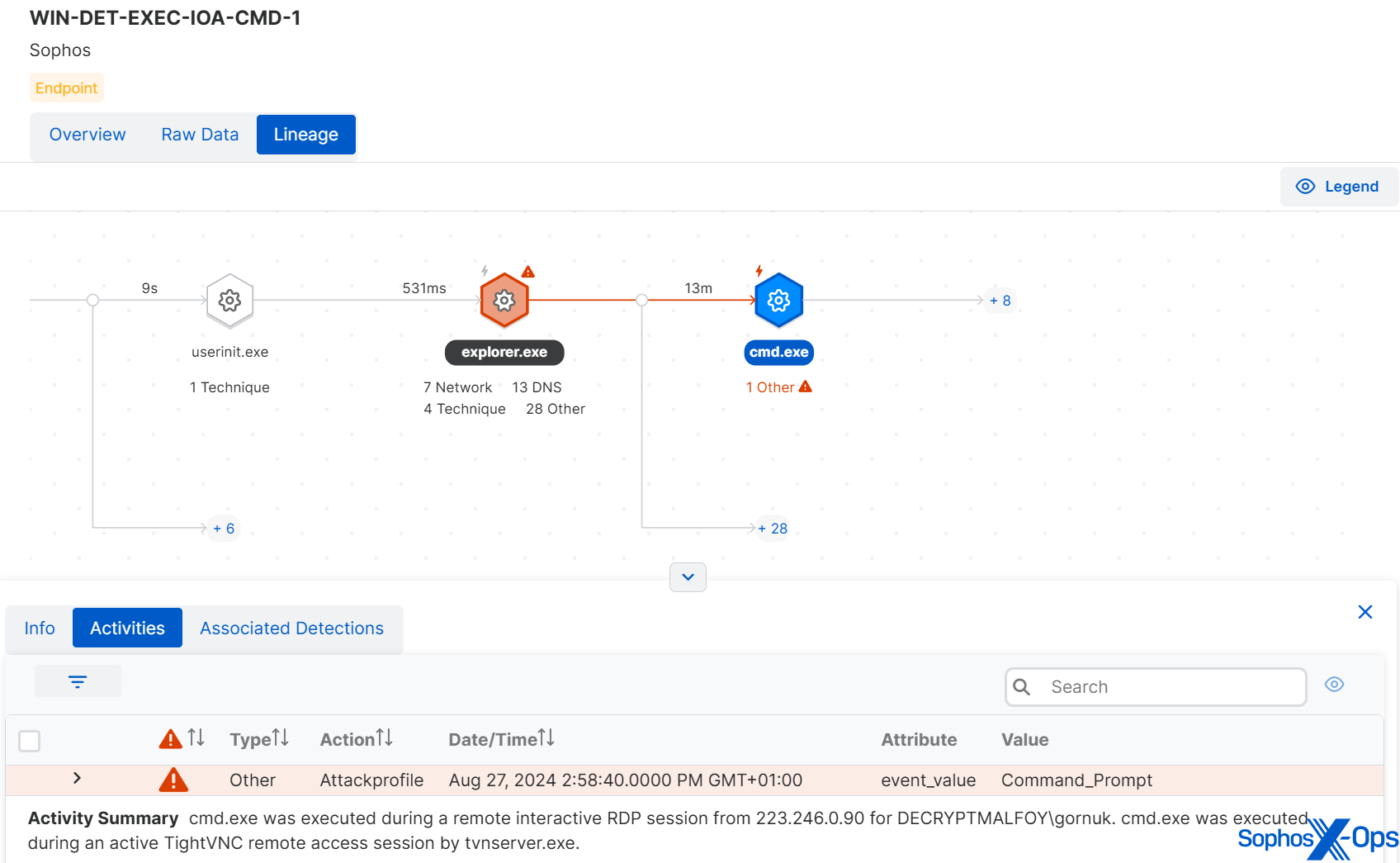

The use of cmd.exe during a remote interactive session served as a significant indicator of the attack. Additional clues included a TightVNC connection and a remote interactive logon from an unfamiliar IP address.

Figure 10: Examination of suspicious activity during the initial ingress phase

Sustainability

To establish continued access within the network, the threat actor proceeded to implement a PowerShell remote access shell identified as ThunderShell. According to CISA’s alert, this tool is commonly used by LockBit affiliates to maintain persistence if the initial access channel is severed. Monitoring recurring network connections helped in identifying unusual ‘beaconing’ actions, enabling the flagging of suspicious processes and connections.

The ‘attacker’ in the MITRE simulation further solidified persistence by utilizing the winlogon automatic logon registry key. While this action slightly diverged from the expected behavior in real-world scenarios, where threat actors often enumerate such keys to potentially uncover plaintext credentials.

Consequence

MITRE decided to imitate the unique LockBit exfiltration tool called StealBit, typically employed by RaaS affiliates for double extortion, a tactic also favored by many other ransomware groups. This methodology facilitates the extraction of sensitive data to an external server before encryption.

The imitation of StealBit by MITRE (dubbed connhost.exe) mimicked the real operation by checking for attached debuggers using the PEB “BeingDebugged” flag and dynamically resolving APIs through LoadLibraryExA and GetProcAddress – with the resolved DLLs obscured using XOR-obfuscated filenames. This approach strongly resembled the actual StealBit malware.

Following data exfiltration, the MITRE ‘threat actor’ replicated the primary LockBit executable to encode data and propagate itself across the network.

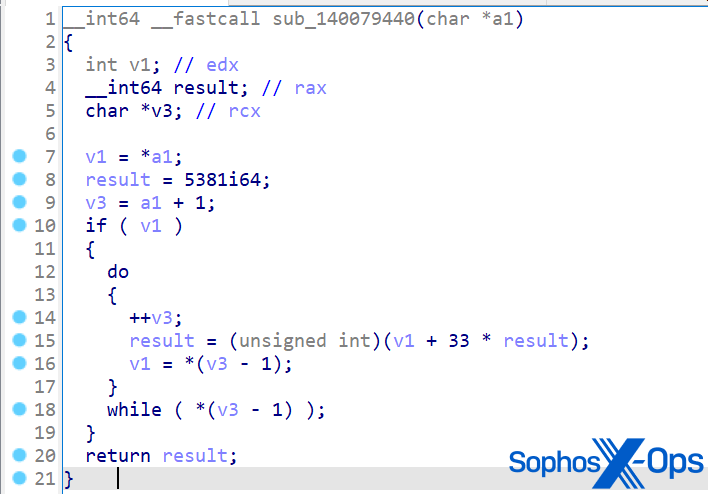

Similar to the genuine version, MITRE’s LockBit sample employed several evasive strategies, such as dynamic API resolution using an in-memory API hashing algorithm (to conceal API names from static scrutiny) and anti-debugging via NtSetInformationThread. These techniques were elucidated in detail in our examination of LockBit 3.0 in 2022, with MITRE choosing to implement DJB2 hashing. This differs from LockBit’s original approach, but achieves the same result while avoiding detection of known IOCs by security vendors.

Figure 11: MITRE’s LockBit utilizing the DJB2 hashing algorithm. The extensive implementation demonstrated MITRE’s dedication to mirroring genuine LockBit functionalities

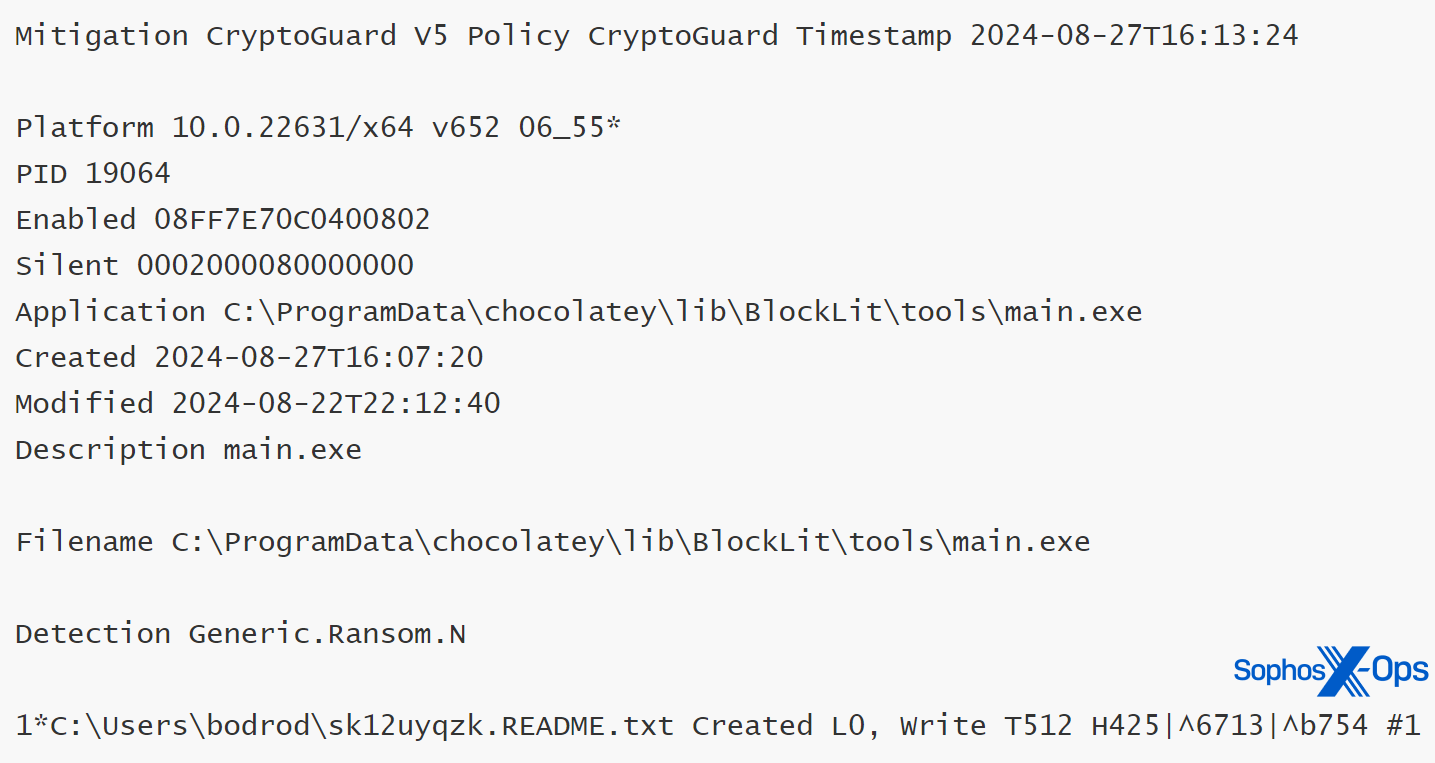

This malicious activity was detected by Sophos using CryptoGuard. It is important to note that during this specific test, CryptoGuard was in monitor-only mode, preventing the encryption rollback. In a separate test focused on defensive measures, encrypted files were successfully rolled back to their original state, even in cases of remote encryption simulations.

Figure 12: CryptoGuard thumbprint information revealing ransomware detection and ransom note creation

2024 marked the fourth year of Sophos’ involvement in MITRE’s ATT&CK Evaluations: Enterprise. The emphasis on genuine attack sequences and realism has made these evaluations highly beneficial for evaluating our capabilities and those of other security providers. We appreciate MITRE’s commitment to transparency.

Accurate and realistic scenarios in these evaluations offer significant value. While minor deviations from actual attacks were noted in MITRE’s tests, mainly due to constraints, the overall resemblance to known campaigns and actors was striking.

Transparent and practical evaluations involving multiple vendors benefit not only the vendors themselves but also their customers and the broader community. We eagerly anticipate future participation in these evaluations and sharing our insights and discoveries whenever feasible.