A group of scholars split between Italy and the UK have recently released a paper discussing cryptographic vulnerabilities discovered in a widely-recognized smart light bulb.

The scholars appear to have selected the TP-Link Tapo L530E as their subject device, as it is “currently [the] top seller on Amazon Italy,” so the comparative vulnerabilities of other smart bulbs are unknown, although their report provides valuable insights regardless.

According to the scholars:

We promptly contacted TP-Link through their Vulnerability Research Program (VRP), documenting all four vulnerabilities we identified.

They acknowledged all issues and informed us of their ongoing efforts to rectify them at both the application and firmware levels of the bulb, with plans to release updates accordingly.

Whether positive or negative (the paper’s authors didn’t mention any agreed disclosure timelines with TP-Link, the duration of the company’s patching efforts remains unknown), the scholars have now disclosed the workings of their attacks, yet refrained from providing exploitable attack code for aspiring home-hackers.

Consequently, we deemed the paper noteworthy to investigate.

Wireless arrangement

Similar to numerous so-called “smart” devices, the Tapo L530E is crafted for swift and effortless setup over Wi-Fi.

Despite wireless-based configuration being prevalent even for rechargeable gadgets, such as cameras and bike accessories, that can be powered and set up via integrated USB ports, light bulbs typically lack USB ports, primarily due to spatial and safety concerns, as they are designed to be inserted into and remain in a mains light socket.

You can induce the Tapo L530E light bulb into setup mode by repeatedly toggling it on and off using the wall switch for brief one-second intervals (allegedly, the bulb blinks three times automatically to indicate readiness for configuration).

Comparable to most auto-configurable devices, this action prompts the smart bulb to transform into a Wi-Fi access point with an easily recognizable network identifier in the format Tapo Bulb XXXX, where the X’s represent a sequence of numbers.

Subsequently, you establish a connection to this transient access point, lacking password protection, from a mobile app on your smartphone.

Thereafter, you instruct the bulb on linking to both your secure home Wi-Fi network and your TP-Link cloud account for future connections, following which the bulb’s firmware initiates reboot and internet connection, facilitating remote management of the bulb via the app on your mobile device.

The bulb can integrate into the home network, enabling direct contact via personal Wi-Fi even when your ISP is offline.

Moreover, the bulb can link to your cloud account over the internet, permitting commands to be dispatched indirectly through your cloud account while you’re away, for instance, controlling light settings to simulate occupancy if you’re delayed.

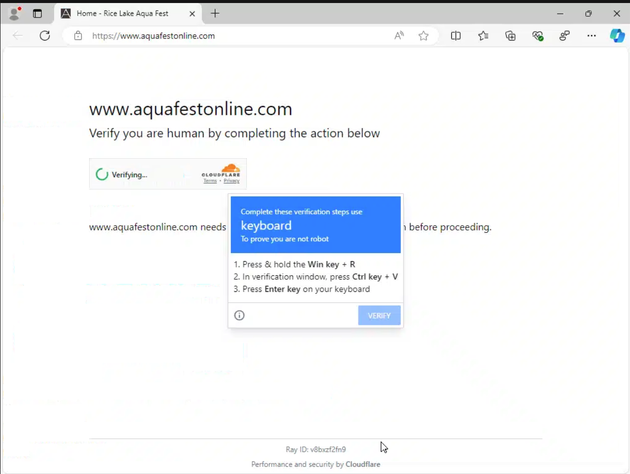

Exercise caution against counterfeit entities

The forthcoming events can be anticipated.

If the app on your smartphone lacks robust cryptographic validation methods to ensure authentic connection to a genuine light bulb during setup…

…then a nearby threat actor could potentially manipulate you into transmitting vital setup credentials to their fraudulent “imposter bulb” device by opportunistically broadcasting a simulated Tapo Bulb XXXX access point, thereby capturing both your Wi-Fi passcode and TP-Link account particulars.

The positive aspect is that the scholars observed basic security measures in both the Tapo app and L530E firmware aiding in reliable mutual identification, thereby alleviating the likelihood of unauthorized password disclosures.

Regrettably, the protocol employed for this are you really a light bulb? verification was evidently formulated to preclude errors rather than deter potential attacks.

Succinctly, the app identifies any light bulbs on its network by broadcasting specialized UDP packets to port 20002 and authenticating responsive devices, if any.

To assist any attentive light bulbs in discerning that the are you there? query originates from the Tapo app, instead of an unverified product or service sharing port 20002, the query includes a keyed hash as part of its composition.

The acknowledgment from the light bulb upon receiving the I am here! request will likewise contain a corresponding keyed checksum for the app to validate the legitimacy of the UDP replies.

In essence, the keyed hash represents a checksum derived not solely from the content within the UDP packet but also integrates auxiliary key bytes for inclusion into the checksum.

Unfortunately, the Tapo’s protocolUtilizes predetermined key bytes for its validation code, with an identical “key” firmly embedded within the application and firmware of each Tapo bulb.

To put it differently, when an individual has decompiled either the application, or the bulb’s firmware, or both, and has managed to retrieve this “key”, it must be assumed that everyone will know what it is, rendering those are you there?/I am here! messages effortlessly counterfeitable.

Even more concerning, the investigators discovered that no decompilation was necessary, as this not-really-secret “key” is merely 32 bits in length, which implies that by placing your own Tapo bulb into setup mode and then transmitting are you there? messages using all 232 conceivable checksum keys, you will eventually land on the correct key through a technique known as brute force.

This equates to the cryptographic equivalent of systematically testing every combination on a bike lock, ranging from 000 to 999, until the lock is successfully opened. (On average, the lock will be opened after attempting half of the possible combinations, but it will not take more than 1000 tries.)

To be precise, they did not require sending 232 messages from the application to a bulb to crack the key.

By capturing a single authenticated message with a valid keyed hash, they could then evaluate all potential keys offline until generating a message with an identical keyed hash as the saved one.

This means the brute force assault could proceed at CPU speed, rather than solely at Wi-Fi network packet speed, and the researchers affirm that “in our configuration, the brute force attack consistently succeeded within 140 minutes on average.”

(Presumably, they conducted repeated attempts solely to verify the functionality of their decryption code, although with a hardcoded key shared by all Tapo bulbs, their initial decryption would have sufficed.)

If you converse confidentially, I’ll accept your identity

The subsequent cryptographic issue surfaced during the subsequent phase of the bulb setup process and exhibited a similar type of error.

After acknowledging a bulb as genuine based on a keyed hash devoid of a actual key, the application consents to a session key for encrypting its communication with the “authentic” bulb…

…nonetheless, there exists no method to validate whether the key agreement occurred with an actual bulb or a counterfeit one.

Establishing a session key is vital in order to safeguard the Wi-Fi and Tapo passwords when they are transmitted from the Tapo application to what is assumed to be a Tapo light bulb.

However, lacking any verification procedure for the key agreement itself is similar to establishing a connection with a website via HTTPS and then neglecting to perform even a rudimentary examination of the web certificate that it responds with: your data may be secure during transit, yet it could still fall into the hands of a fraudster.

The Tapo application authenticates to the bulb (or the supposed bulb) by dispatching an RSA public key, which is utilized by the counterpart to encrypt a randomly generated AES key for securing the data exchanged during the session.

Nonetheless, the bulb device fails to provide any kind of identification, not even a checksum with a fixed 32-bit key, back to the Tapo application.

Thus, the application has no option but to receive the session key without determining if it was sourced from a genuine bulb or a fake device.

The collective result of these dual flaws is that a malicious individual on your network might initially persuade you that their unauthorized access point was a legitimate bulb awaiting configuration, thereby leading you astray, and then coax you into transmitting an encrypted replica of your Wi-Fi and Tapo passwords to it.

Ironically, those disclosed passwords would genuinely be secure against all… excluding the phony individual with the unauthorized access point.

Single-use numeric code reused continuously

Regrettably, there’s more.

When we earlier indicated that “those leaked passwords would genuinely be secure,” that was not entirely correct.

The session key formed during the key agreement mechanism explained earlier is not managed correctly, since the developers erred in their utilization of AES.

When the application encrypts each request sent to a bulb, it applies an encryption mode called AES-128-CBC.

We won’t delve into CBC (cipher-block chaining) here, but we’ll just mention that CBC mode is devised in such a way that if you encrypt the same data chunk multiple times (e.g., repeated requests to turn light on and turn light off, where the raw data in the request remains the same each time), the output will not be identical each time.

If every light on and light off request were to yield identical results, then once an attacker had determined the appearance of a turn it off packet, they could not only recognize those packets in the future without decryption, but also replay them without the need to comprehend the encryption process.

Consequently, CBC-based encryption relies on “seeding” the encryption procedure for each data chunk by initially blending a distinct, randomly chosen data block into the encryption process, thereby establishing a unique series of encrypted data in the remainder of the chunk.

This “seed” data, known as an IV in technical jargon, short for initialisation vector, while not meant to be confidential, does need to exhibit unpredictability every time.

Simply stated: identical key + unique IV = distinctive ciphertext output, but identical key + identical IV = foreseeable encryption.

Unluckily, the TP-Link programmers generated an IV concurrently with their creation of the AES session key, and then repeated the same IV with each subsequent data packet, even when the previous data was repeated verbatim.

That is a cryptographic blunder.

Have I transmitted six packets, or merely five?

The concluding cryptographic issue discovered by the researchers is one that could still undermine security even if the initialisation vector predicament was rectified, that is, old messages, whether or not understood by an attacker, can be replayed later as if they were fresh.

Typically, cryptographic protocols tackle this type of replay attack by integrating some form of sequence number or timestamp, or both, into each data packet to restrict its validity.

Similar to the date on a train ticket that would expose you if you attempted to use it consecutively, the sequence numbers and timestamps in data packets serve two crucial objectives.

Primarily, attackers would be unable to record traffic today and effortlessly replay it later, potentially creating chaos.

Secondarily, faulty code that erroneously transmits requests repeatedly, for instance due to missed responses or absent network acknowledgments, can be reliably identified and managed.

What course of action to take?

If you’re a Tapo light bulb user, stay vigilant for firmware updates from TP-Link that remedy these concerns.

If you’re a developer accountable for securing network traffic and network-based product configurations, review the research paper thoroughly to ensure that similar errors have not been made.

Recall the subsequent guidance:

- Cryptography isn’t solely about confidentiality. Encryption represents just one facet of the cryptological triad of confidentiality (encrypt it), authenticity (verify the recipient), and integrity (ensure no tampering occurred in transit).

- Ensure any one-time keys or IVs are genuinely unique. The relevant cryptographic term nonce, short for number used once, is a term that clearly warns against reusing such data. (Technically, IVs are required to be truly random, while nonces may follow a sequence such as 000..001, 000..002, and so forth, yet the critical aspect is that the IV must be initialized each time a new data chunk is encrypted, not solely during key initialization at the outset.)

- Guard against replay attacks. This constitutes a distinct element of ensuring the authenticity and integrity previously mentioned. An adversary should be unable to capture a current request of yours and replay it blindly later without detection. Keep in mind that understanding the message is irrelevant if it can be replayed to wreak havoc.

About Author