Being Authentic: Sophos and the 2024 MITRE ATT&CK Trials: Corporate

Annually, multiple security solution providers – such as Sophos – enroll for MITRE’s ATT&CK Trials: Corporate, a comprehensive cyber breach simulation involving one or more scenarios based on tangible threat actors and their strategies, tools, and methods.

The assessment is structured to offer a realistic (and transparent – the outcomes are publicly accessible) evaluation of security solutions’ performances, centered on end-to-end attack sequences covering initial entry, persistence, lateral movement, and consequences. The simulations typically encompass a multi-device ‘client’ setup, equipped with endpoints, servers, domain-connected devices, and Active Directory-managed users.

2024 marked Sophos’ fourth year in participation, and to commemorate this, we sought to provide insights into the contents of this year’s evaluation and to demonstrate its authenticity. Specifically, we will delve into the realism of the tools, intricacies in the testing approach, and Sophos’ shielding and detection capabilities. Though we can’t cover everything (each scenario entails 20-40 steps!), we will spotlight certain elements, underscoring the depth and precision of the simulations.

For the 2024 evaluation, MITRE opted for two threat types, Ransomware and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). The former, an enduringly significant cyber security menace in the field, continues to evolve (e.g., the surge in remote encryption). The latter is also pertinent, given the rise in state-backed espionage attacks linked to the region.

MITRE fashioned three scenarios around these classifications: an assault by a DPRK-related threat actor concentrating on MacOS (tracking threat actors targeting MacOS in various operations, an inclination that seems poised to persist), and assaults by associates of two ransomware gangs (Cl0p and LockBit).

DPRK

The DPRK scenario was uncomplicated yet authentic, mirroring the progression of the JumpCloud supply chain breach: an assailant compromises a device, establishes a persistent agent, and exfiltrates credentials. DPRK-affiliated threat actors are recognized for segmenting their attacks into distinct phases and upholding backdoors for future strikes.

Initial Entry

While the evaluation assumes a supply chain infiltration, the scenario itself implicated a user downloading and executing a malevolent Ruby script (our scrutiny revealed a user execution route of Ruby). In an actual supply chain attack, the script would potentially auto-execute via pre-installed software. Nonetheless, this remains a probable and significant approach – DPRK-linked aggressors employ social engineering to coax users into launching a script, as evidenced in recent cases.

Similar to the JumpCloud incursion, MITRE’s Ruby script (dubbed start.rb, thematically akin to the genuine script name: init.rb) downloads and executes a primary-stage C2 agent (a Mach-O binary), disguised as a docker-related component. It should be highlighted that deciphering authentic JumpCloud specimens is unattainable; as far as we know, the actual samples are not in the public domain. As with all MITRE ATT&CK Trials, the malware employed was custom-made for the evaluation.

Persistence

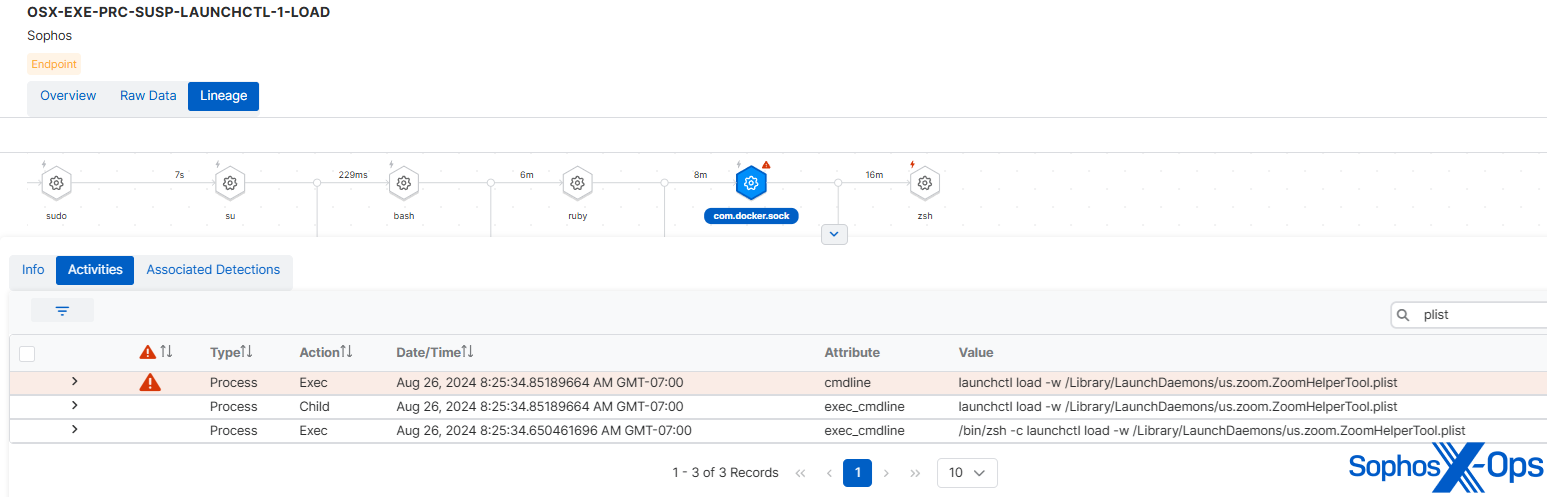

The first-stage C2 agent subsequently fetched a second-stage backdoor (identified as ‘STRATOFEAR’ in the real-world JumpCloud breach), which established persistence much in the same way as the genuine article, utilizing LaunchDaemons (/Library/LaunchDaemons/us.zoom.ZoomHelperTool.plist).

Figure 1: Implementing persistence via ZoomHelperTool.plist

Aligned with the Ruby script in the Initial Access phase, MITRE fashioned the backdoor to closely mirror reality. The backdoor was deposited in the same locale (/Library/Fonts), sporting a near-identical name (the genuine version was named ArialUnicode.ttf.md5, whereas the evaluation iteration was pingfang.ttf.md5; both ‘Arial’ and ‘pingfang’ denote authentic fonts).

As in the genuine JumpCloud incursion, the ‘threat actor’ displayed stealth and elusiveness, swiftly removing the primary-stage implant files from the system. In the simulation, they accomplished this through an rm -f <FILE> command, as per our analysis. While we can’t confirm if this mirrored the approach of the JumpCloud threat actor (given that direct API methods are quieter, compared to process executions that are more apt to be recorded), as previously stated, the real-world samples are inaccessible.

Similarly to the legitimate STRATOFEAR, the MITRE backdoor utilized encrypted configuration files, employing a shell-out openssl enc -d command and a hardcoded password. Once again, utilizing a direct API-oriented method would enhance stealth, though we lack clarity on whether the JumpCloud threat actor adopted that tactic.

A brief note regarding test integrity: MITRE employs domains for its C2 infrastructure that function within the test setting’s restrictions but are not resolvable publicly via DNS. Nonetheless, they map to public IP addresses. Consequently, the network traffic appears authentic C2 activity, albeit the domains remain inaccessible beyond the test platform.

Consequences

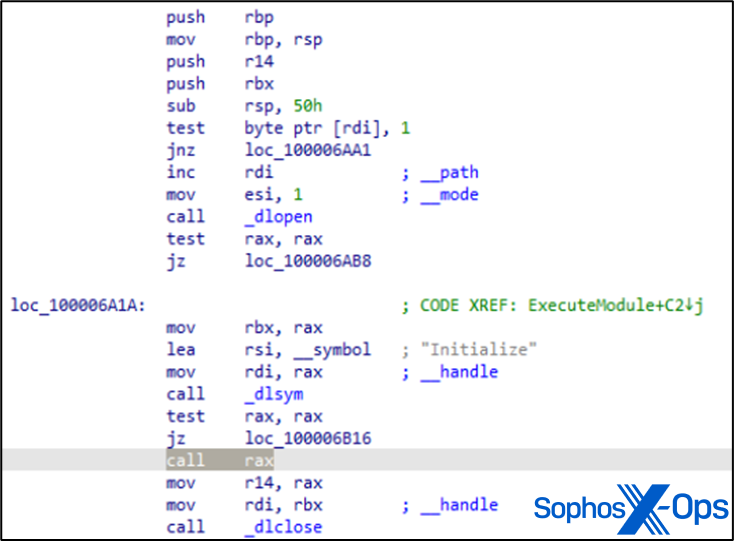

Much akin to the JumpCloud breach, the threat actor’s objective is data gathering, encompassing system details, credentials, and sensitive data within the Keychain. MITRE’s STRATOFEAR backdoor faithfully replicated the original, fetching and executing supplemental modules from the C2 server.to perform the robbery. Similar to the modules fetched by the genuine STRATOFEAR, these were scripted to a .tmp document in the /tmp folder, each designated with a string of six chance alphanumeric characters.

During the analysis, MITRE’s STRATOFEAR acquired /private/tmp/rhkA2f.tmp, a module capable of scanning MacOS keychain files.

Figure 2: MITRE’s STRATOFEAR sample showcasing the ExecuteModule function, utilizing dlopen/dlsym to trigger an ‘Initialize’ function

This sequence culminated in the secret entrance collecting the information; the assessment did not incorporate any active data extraction. While some may criticize this as a flaw in the methodology – credentials typically only hold value if leaked – we posit that it’s a minor issue. If you, as an incident responder, can detect credential theft, you’ll comprehend the potential repercussions and the related malevolent actions.

Cl0p

The subsequent scenario entailed an imitation of an assault by the Cl0p ransomware gang (also recognized as TA505), a productive threat actor. Here, the progression of the attack closely imitated – to a substantial extent – that of a 2019 episode, comprising a downloader, a persistent RAT, sophisticated process infusion, and exploitation of a trusted process – ultimately leading to a ransomware payload.

Initial entry

While the majority of the scenario adhered to the 2019 real-world campaign, the initial entry phase varied slightly. Similar to 2019, the threat actor deployed a DLL to establish a persistent RAT. However, in contrast to the real-world attack involving malicious Office files incorporating an embedded DLL, which was dynamically integrated into the Office process, the MITRE scenario featured a user executing cmd.exe and initiating the DLL via rundll32.exe.

This DLL was already stored on the host, having been acquired through a curl directive from a separate interactive cmd.exe (this step wasn’t part of the scenario) subsequent to initial entry via RDP. It’s crucial to acknowledge that this approach to initial entry is frequently employed by ransomware groups and other threat actors, particularly when procuring stolen credentials/access via initial access brokers (IABs). However, in one prominent instance, Cl0p also exploited a zero-day vulnerability in the MOVEit file transfer application (CVE-2023-34362).

Although it’s plausible for an attacker to gain direct remote access to the compromised host, the scenario perhaps could have encompassed the importation of the DLL toolset for a more comprehensive simulation.

Resilience

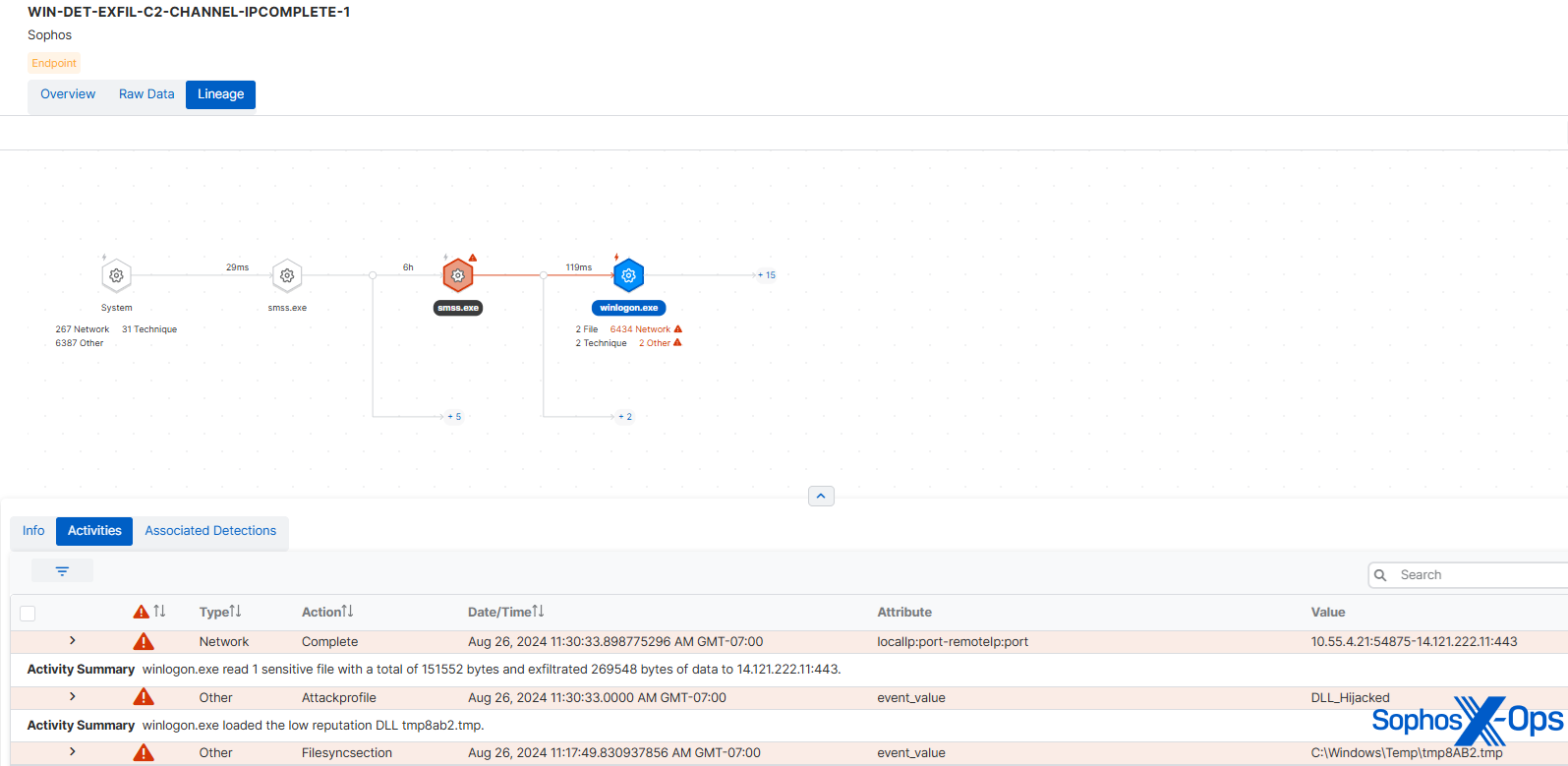

Per the 2019 campaign, the MITRE ‘threat actor’ injected the persistent RAT SDBbot by undermining the trustworthy winlogon.exe process, employing Image File Execution Options (IFEO) injection with a ‘VerifierDLL’ key.

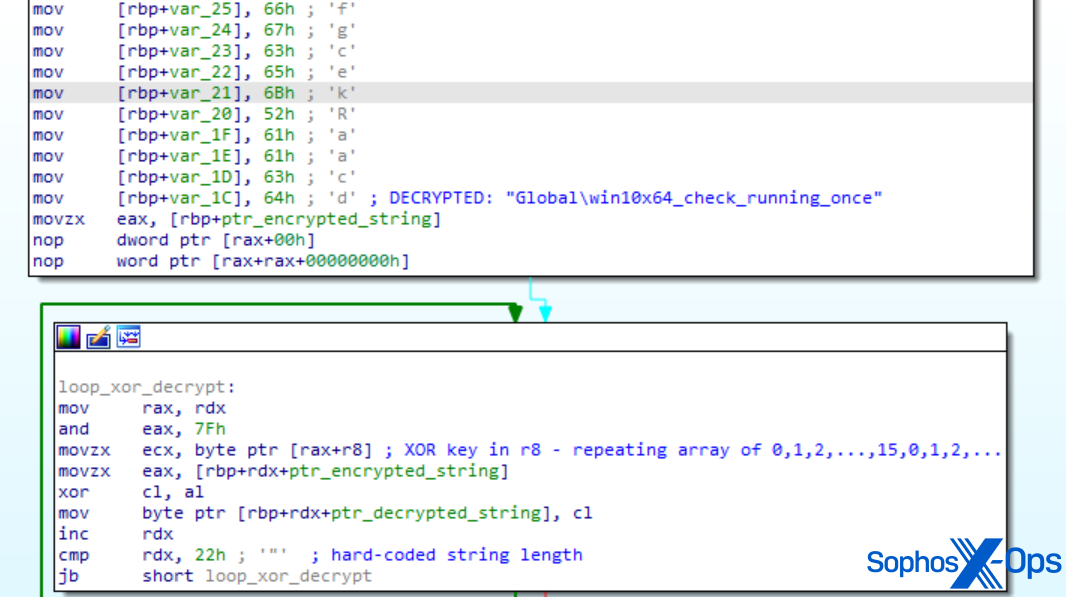

SDBbot utilizes encrypted sequences and a mutex to safeguard its startup. Similar to the DPRK scenario, the MITRE sample employed a mutex name resembling but different from the one in the real-world attack (‘windows_7_windows_10_check_running_once_mutex‘ in the actual attack, ‘win10x64_check_running_once‘ for the assessment).

Figure 3: Disassembly of MITRE’s SDBbot sample. Note the mutex name and the decryption function

In MITRE’s rendition of SDBbot, the encryption material comprises a series of the same 16 ascending bytes from 0 to 15. While this is less secure than a truly random 128-byte string – it suffices to obscure the sequences used to denote API names and data fields beyond simplistic static assessment procedures. MITRE implemented this technique of sequence obfuscation throughout the Cl0p scenario, as well as in the LockBit scenario examined below.

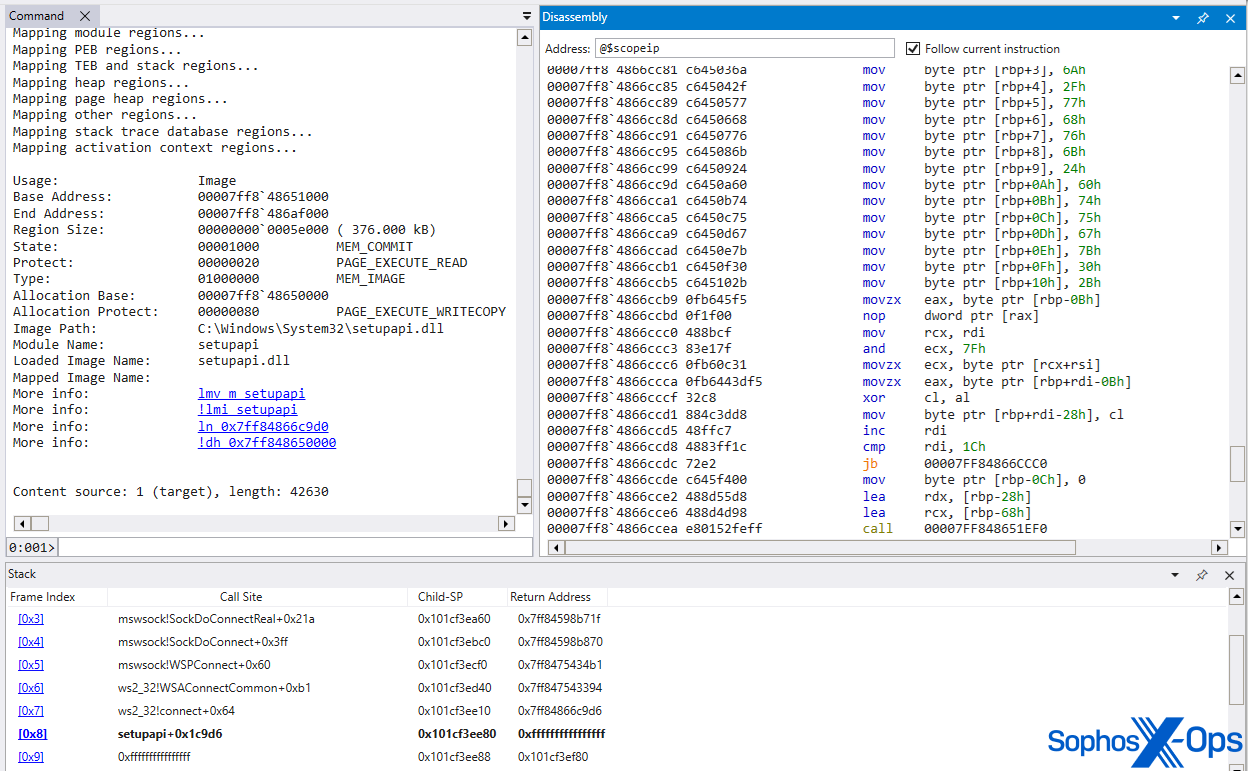

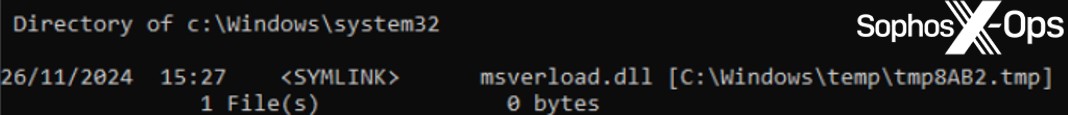

MITRE’s sample was injected through a reflective loader, replacing image memory in setupapi.dll. Given that the RAT resides in standard ‘image’ memory, it’s more challenging to detect than if it were in dynamically allocated heap memory. This represents a refined injection tactic intended to circumvent modern defenses. MITRE’s strategy introduced an additional challenge when attempting to detect the actions of the installer (the rundll32 process) releasing the SDBbot loader component. The installer placed the loader in a %TEMP% location but established a symbolic link to that path in the SYSTEM directory, and the IFEO registry entry was configured to point to the SYSTEM directory path – thus creating an added layer of abstraction between the installer and the enduring RAT.

Figure 4: The symbolic link for the msverload.dll loader

Figure 4: The symbolic link for the msverload.dll loader

The utilization of the ‘VerifierDLLs’ technique introduced further intricacy to the execution flow, as the loader (msverload.dll) was embedded into the winlogon.exe process space before the process’s entry point. Subsequently, it employed VirtualAlloc to insert and execute embedded shellcode, and VirtualProtect to make the otherwise RX image memory of setupapi.dll writable before replacing its contents with the SDBbot RAT. The memory permissions were later reconfigured to RX to maskthe code resembles that of a ‘regular’ image memory – like a DLL would when directly loaded from the disk.

Figure X: MITRE’s SDBbot is loaded, and replaces the module of the otherwise genuine setupapi.dll IMAGE memory, with memory protections reset to PAGE_EXECUTE_READ

In this case, our detection approach involved multiple facets: having C2 activity originate from a winlogon process is suspicious, and C2 activity itself triggers common memory scans (as touched upon in a blog post discussing this matter in 2023). Memory scans also picked up a shellcode pattern. The suspicious C2 event enabled Sophos Detection to capture the data exfiltration behavior, and we observed that the data exfiltration method – using SDBbot and transmitting data over the C2 channel – was adopted by Cl0p in 2020.

Figure 6: Detecting exfiltration during the Cl0p scenario

Consequences

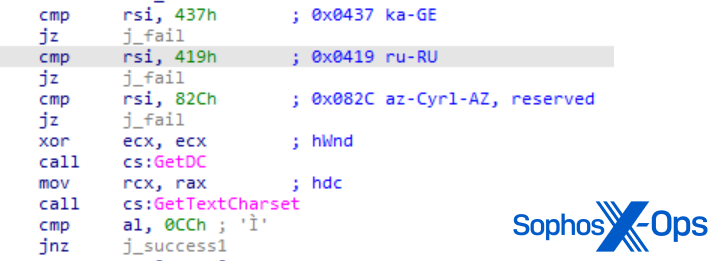

MITRE’s rendition of the Cl0p ransomware sample (sysmonitor.exe, acquired via SBDbot) closely imitated an actual sample from 2019. Just like the authentic version, MITRE’s sample utilized GetKeyboardLayout to verify the layout in use for Russia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan (to avoid targeting systems using them). It also employed a similar check for the GetDC/GetTextCharset APIs, aiming to achieve the same goal.

Figure 7: MITRE’s Cl0p sample invoking GetDC and GetTextCharset to check for infected hosts in Russia, Georgia, or Azerbaijan

We also observed several near-identical matches in behavior and methodology, notably in how the ransomware handles shadow volumes and the attempt to disable various services on compromised devices.

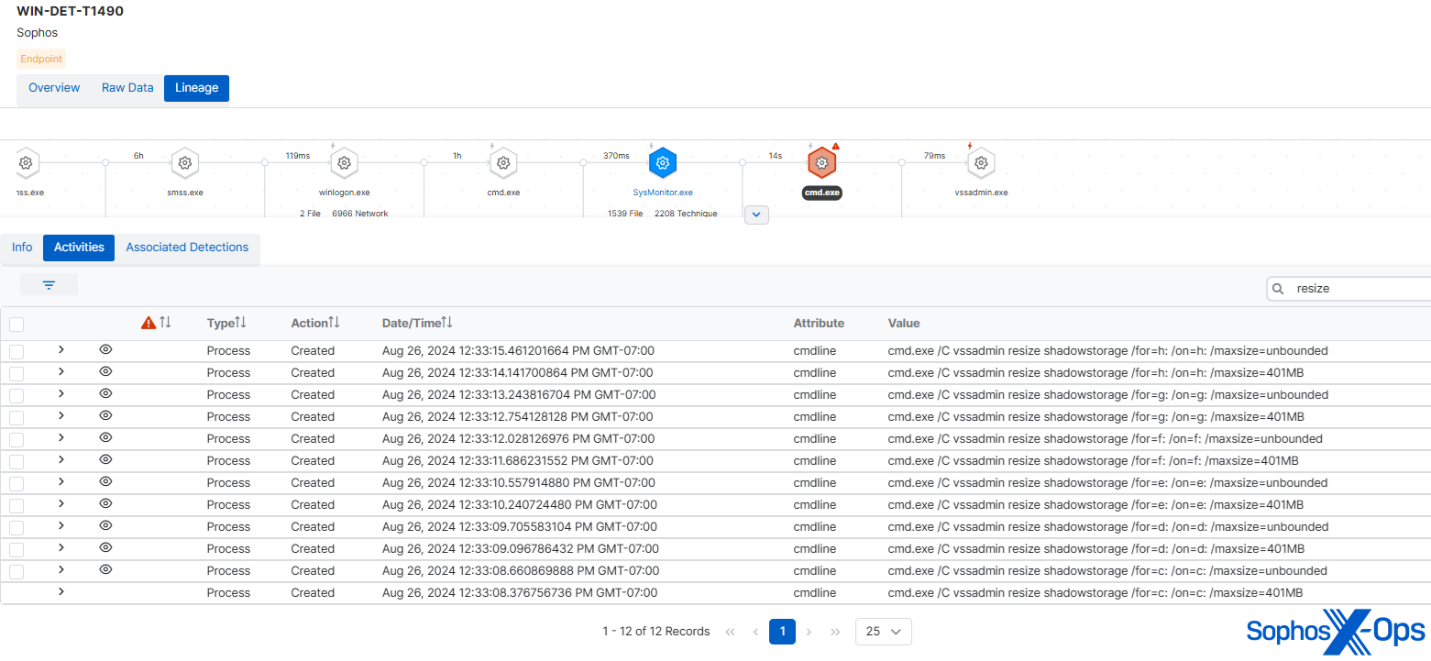

Many ransomware strains will try to erase shadow volumes to hinder data recovery efforts, followed by resizing the shadow storage to prevent further creation of such volumes. However, the 2019 Cl0p ransomware executed the latter step in a specific manner, cycling through a preset list of drives (from C to H). MITRE’s sample faithfully replicated this behavior.

Figure 8: MITRE’s emulation of Cl0p cycling through various drives to resize the shadow storage

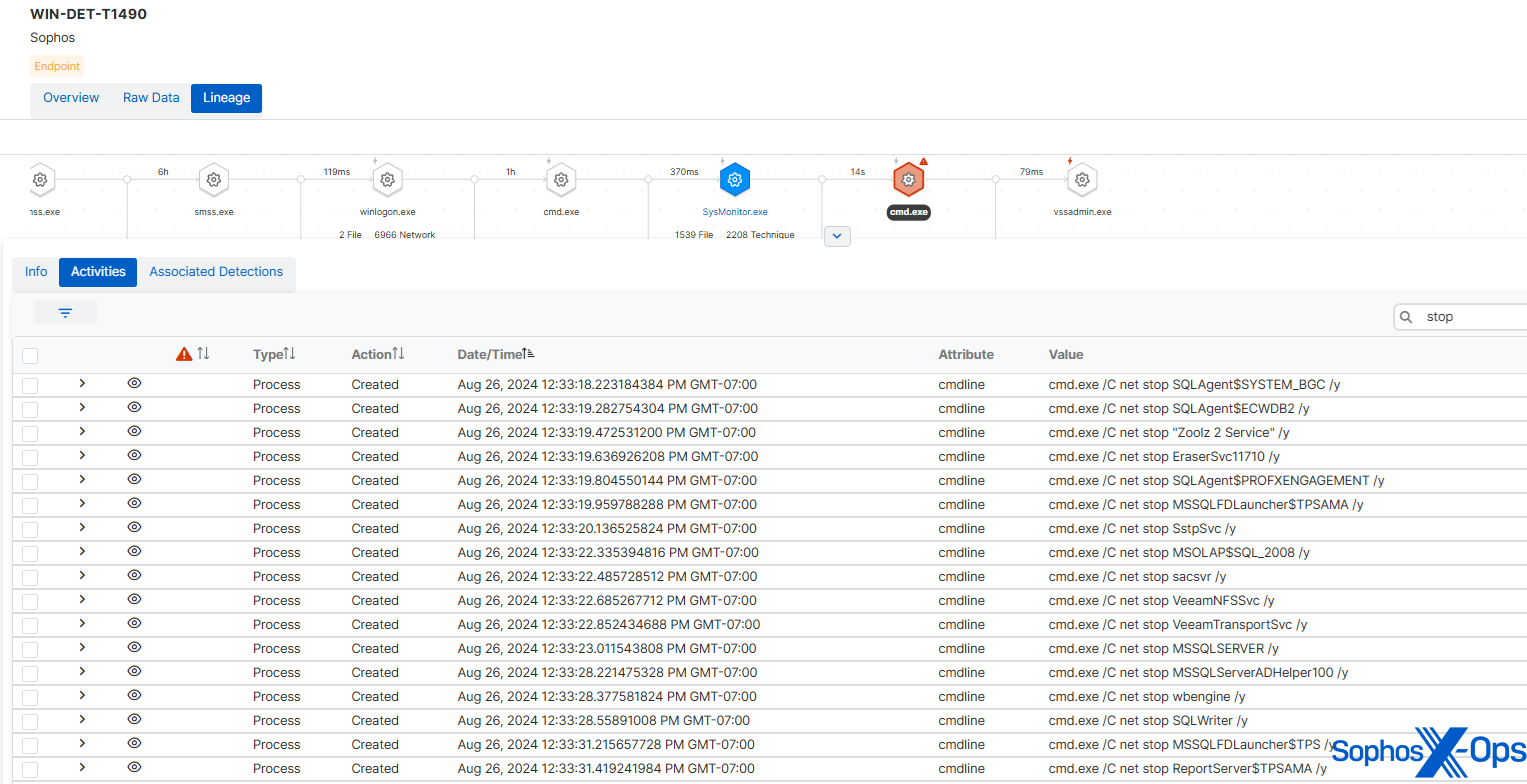

Furthermore, like many other ransomware variants, the Cl0p ransomware iterates through a range of services – encompassing security services and those containing crucial data for encryption – and tries to halt them via net stop.

MITRE’s sample adhered to the same service list as the authentic Cl0p ransomware, following the same sequence – albeit leaving out security services, likely to avoid disruption during testing.

Figure 9: Sophos detection, displaying the net stop commands utilized in MITRE’s Cl0p sample

As for its file encryption methodology, the MITRE malware utilized AES, adding a unique marker (“Cl1pCl0p!?“) to the data within encrypted files. This strategy mirrored that of the authentic malware, which employed the marker “Clop^”. However, while the 2019 samples leveraged the advapi32.dll CryptAcquireContextW API for crypto algorithm support, the MITRE version opted for the open-source CryptoPP library – a more contemporary approach embraced by many ransomware families today.

LockBit

LockBit, akin to Cl0p, operates as an active ransomware faction, albeit one significantly disrupted by law enforcement entities in February 2024. Nevertheless, owing to a Leaked LockBit builder in 2022, threat actorsproceed with executing its ransomware. MITRE’s LockBit scenario presented TTPs recognized to be utilized by some LockBit associates (similar to the Cl0p scenario, it should be noted that although the behavior of ransomware binaries generally remains consistent across attacks since they are created and dispersed centrally, affiliates might have more flexibility in their approaches, resulting in different playbooks – and consequently TTPs and IOCs – that may vary). These TTPs involved the initial access technique, the utilization of ThunderShell and PsExec, and various evasion tactics.

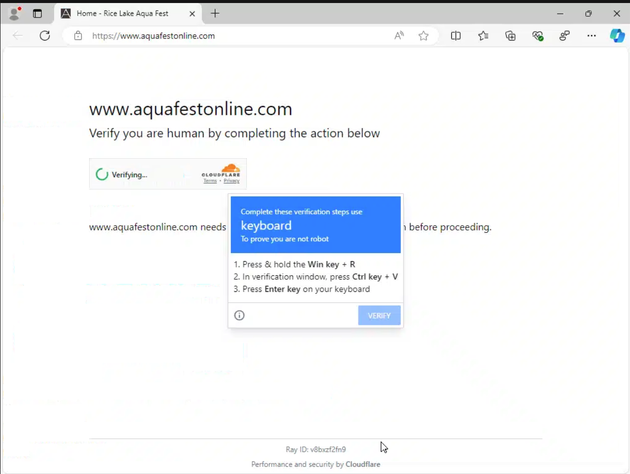

Initial entry

The MITRE ‘adversary’ initiated their assault by establishing authentication via an outward-facing TightVNC service (a legitimate remote administration tool), utilizing credentials that had been previously compromised. Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) affiliates frequently acquire initial access in this manner using previously compromised services and credentials available for purchase on cybercrime forums, as previously mentioned in the Cl0p scenario.

Once access was obtained, the attacker executed a variety of discovery commands, which correlated with commands commonly seen early in a RaaS attack, such as:

nltest /dclist:<domain>

cmdkey /list

net group “Domain Admins” /domain

net group “Enterprise Admins” /domain

net localgroup Administrators /domain

powershell /c "get-wmiobject Win32_Service |where-object { $_.PathName -notmatch "C:Windows" -and $_.State -eq "Running"} | select-object name, displayname, state, pathname

These commands closely resembled those observed during a LockBit attack in 2022.

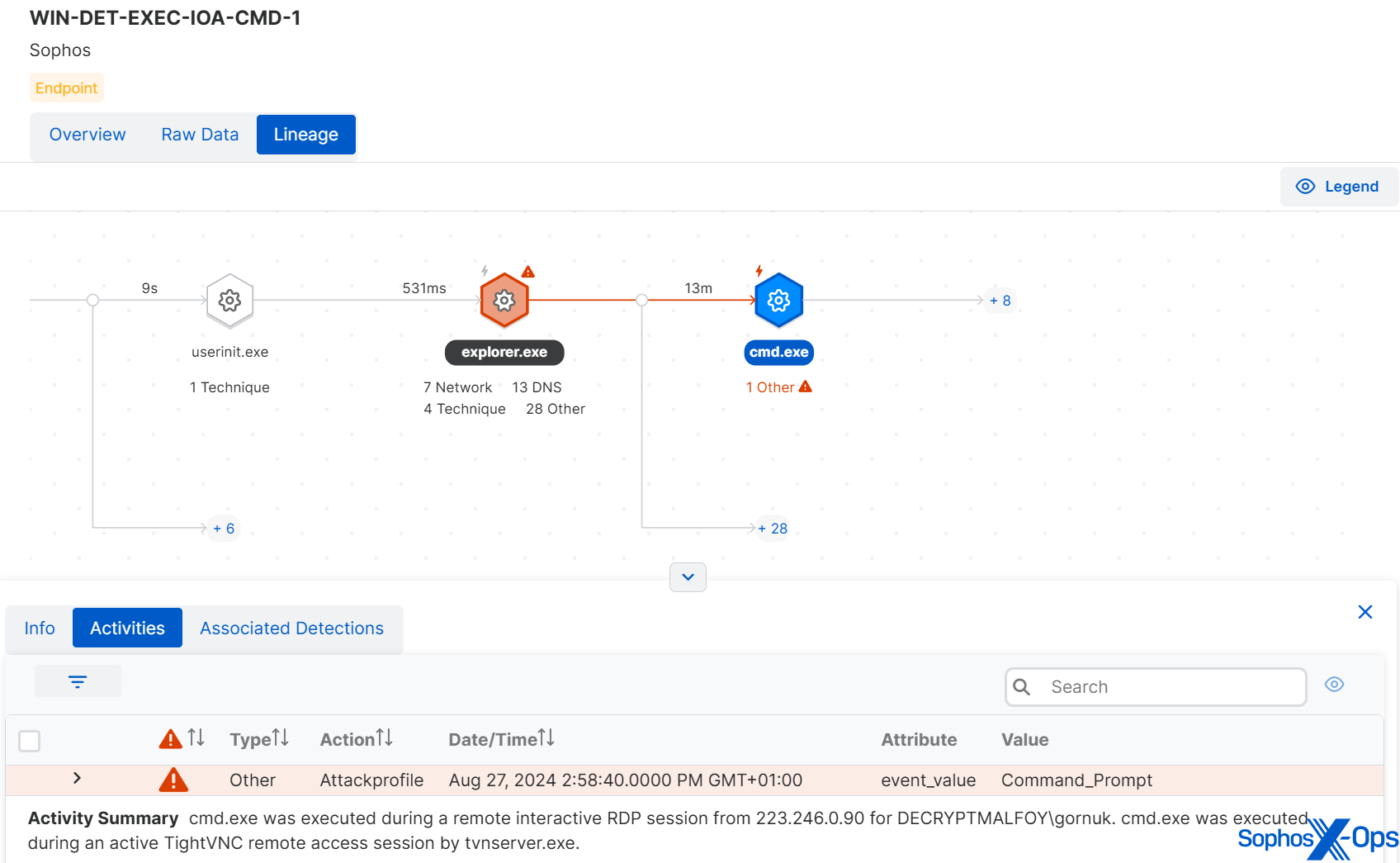

The execution of cmd.exe during a remote interactive session acted as a significant indicator of the attack, alongside a TightVNC connection and remote interactive logon from an unidentified IP address.

Figure 10: Examination of suspicious activities during the initial access phase

Maintaining Presence

To sustain a foothold in the system, the threat actor consequently implemented a PowerShell remote access shell known as ThunderShell. As remarked by CISA, this tool is recognized to be utilized by LockBit affiliates, allowing them to retain persistence in case of losing the initial access method. Here, we managed to track recurring network connections to identify ‘beaconing’ actions and identify suspicious processes and connections.

The MITRE ‘attacker’ further secured persistence through the winlogon automatic logon registry key. This step slightly deviated from what would be expected in a real-world situation; typically, threat actors would enumerate these keys to potentially uncover plaintext credentials.

Outcomes

MITRE chose to simulate the customized LockBit exfiltration tool StealBit, used by RaaS affiliates for double extortion (a methodology frequently employed by various other ransomware factions) – enabling the exfiltration of sensitive data to a distant server prior to encryption.

MITRE’s version of StealBit (referred to as connhost.exe), much like the authentic tool, applied a PEB “BeingDebugged” flag to check for attached debuggers, alongside performing dynamic API resolution using LoadLibraryExA and GetProcAddress – with resolved DLLs saved as XOR-obfuscated filenames. This closely resembled the approach seen in the authentic StealBit malware.

Following the exfiltration process, the MITRE ‘threat actor’ introduced a replicated form of the primary LockBit executable to encode data and propagate throughout the system.

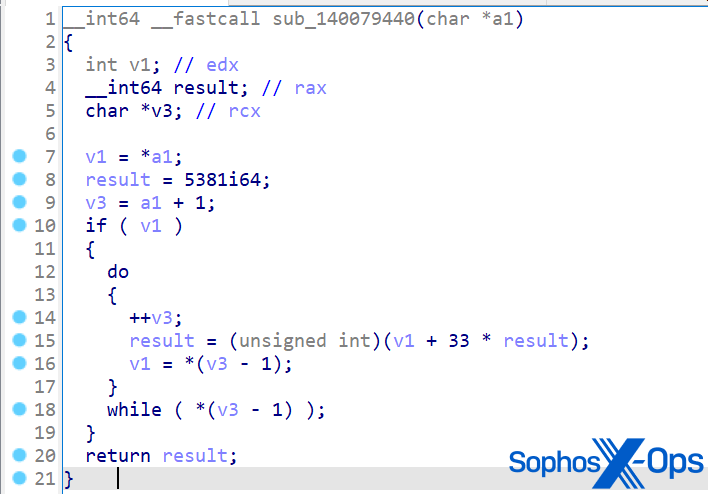

Similar to the real-world variant, MITRE’s LockBit sample employed various evasive strategies, including dynamic API resolution utilizing an in-memory API hashing algorithm (to conceal API names from static analysis) and anti-debugging via NtSetInformationThread. We documented both these techniques in our examination of LockBit 3.0 in 2022, with the note that MITRE’s implementation used DJB2 hashing. This stood in contrast to the original LockBit approach (a custom implementation utilizing a ROR-based hashing method with a seed key), but achieved the same outcome, while also avoiding the inclusion of a known IOC that we and other vendors might have previously identified.

Figure 11: MITRE’s adaptation of LockBit integrated the DJB2 hashing algorithm. This represented a complex implementation, with clear efforts to replicate the functionality of the genuine LockBit binary

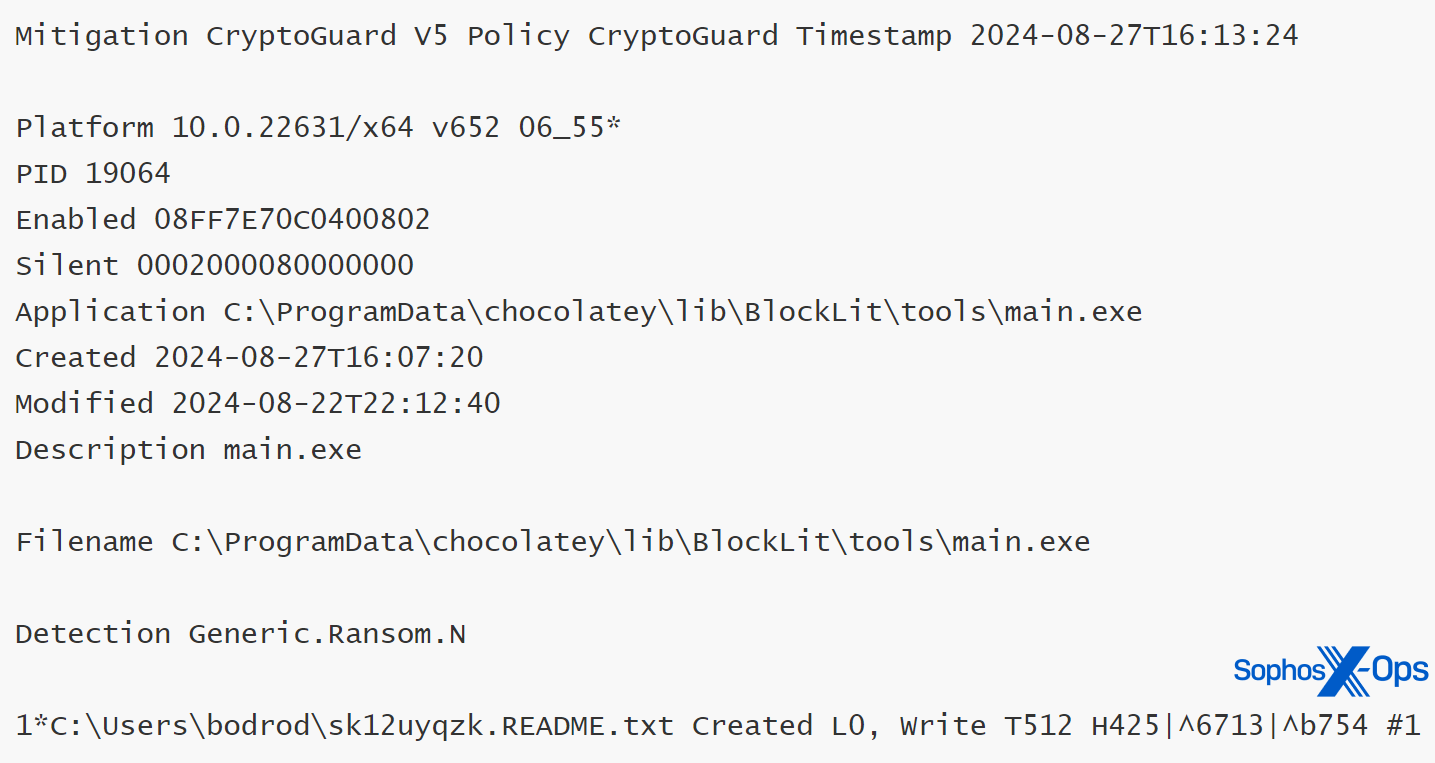

Sophos identified this activity using CryptoGuard, though it should be acknowledged that as this specific test was conducted in monitor-only mode, CryptoGuard did not reverse the encryption. In a separate test focused on safeguards, encryption activity led to the encrypted files being reverted to their original state, even in situations of remote encryption simulations.

Figure 12: CryptoGuard thumbprint information demonstrating the identification of ransomware activity and the creation of a ransom note

2024 marked the fourth consecutive year in which Sophos participated in MITRE’s ATT&CK Evaluations: Enterprise. Similar to prior years, the focus on end-to-end attack sequences and practicality has rendered the assessment a highly valuable endeavor in gauging our capabilities and those of other vendors. We also appreciate MITRE’s dedication to transparency.

Just like any emulation, the efficacy of these evaluations largely hinges on the accuracy and realism of their scenarios. While deviations from real-world attacks were observed in a few instances in MITRE’s tests – often due to unavoidable constraints – the overall resemblance to known campaigns and threat actors was notably strong.

Transparent, practical assessments, involving multiple vendors, benefit not only the vendors themselves but also customers, consequently benefiting society at large. We eagerly anticipate continued participation in such evaluations in the future, sharing our insights and observations whenever possible.