Analyzing patch prioritization: Exploring frameworks and solutions – Part 2: Alternative frameworks

In the preceding segment of this sequence, we delved into the intricacies of CVSS and its operational methodology, concluding that while CVSS might present certain advantages, it is not intended to serve as the exclusive basis for prioritization. In this writing, we will discuss various substitute tools and systems for remediation prioritization, exploring how they can be applied, and evaluating their strengths and limitations.

EPSS, initially unveiled at Black Hat USA 2019, is under the stewardship of a FIRST Special Interest Group (SIG), akin to CVSS. The accompanying whitepaper from the Black Hat presentation suggests the EPSS originators seek to address a void in the CVSS structure by prognosticating the likelihood of exploitation based on historical data.

The primary iteration of EPSS involved logistic regression: a statistical methodology to ascertain the likelihood of a binary outcome by assessing the collective impact of multiple standalone variables on that outcome. For illustration, if one were to employ logistic regression to gauge the likelihood of a yes/no occurrence (such as whether an individual would buy a product), one would gather substantial historical marketing data on former patrons and potential customers. The independent variables would encompass factors like age, gender, income, disposable income, profession, location, prior ownership of a competing product, among others. The dependent variable would signify whether the individual purchased the product.

The logistic regression model would unveil the variables significantly influencing the outcome, either positively or negatively. For instance, it might disclose that individuals younger than 30 with salaries exceeding $50,000 exhibit a positive correlation with the outcome, while pre-existing ownership of a similar product is understandably negatively correlated. By weighing these variables’ impacts, fresh data can be inputted into the model to forecast an individual’s likelihood of purchasing the product. It is crucial to assess the predictive precision of logistic regression models (considering potential false positives or negatives), achievable through Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves.

The EPSS developers analyzed over 25,000 vulnerabilities from 2016 to 2018, isolating 16 noteworthy independent variables, including the impacted vendor, existence of exploit code in the wild (within Exploit-DB or exploit frameworks like Metasploit and Canvas), and the number of citations in the documented CVE entry. These constituted the independent variables, while the dependent variable indicated if the vulnerability had been exploited in the wild (based on data from Proofpoint, Fortinet, AlienVault, and GreyNoise).

They determined that the presence of weaponized exploits made the most substantial positive contribution to the model, followed by Microsoft being the implicated vendor (likely due to the numerous and popular products developed and released by Microsoft, along with its history of being targeted by malicious entities); proof-of-concept code availability;

and Adobe being the affected vendor.

Intriguingly, they also detected negative correlations, such as Google and Apple being the impacted vendors. They speculated that this might stem from Google products harboring numerous vulnerabilities, with relatively few being exploited in the wild, and Apple’s status as a closed platform that threat actors historically overlook potentially. The intrinsic characteristics of a vulnerability (as reflected in a CVSS score) appeared to exert minimal influence on the outcome – albeit, unsurprisingly, remote code execution vulnerabilities were more prone to exploitation compared to local memory flaws.

EPSS initially manifested as a spreadsheet, providing an estimation of the likelihood that a given vulnerability would be exploited within the ensuing 12 months. Subsequent EPSS iterations embraced a centralized configuration with a more advanced machine learning model, expanded the feature array (incorporating aspects like public vulnerability registries, Twitter / X mentions, integration into offensive security tools, correlation of exploitation patterns with vendor market share and user base, and the vulnerability’s age), and assessed the likelihood of exploitation within a 30-day timeframe rather than a year.

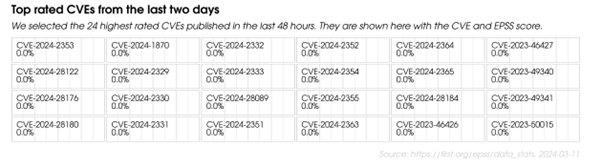

Figure 1: A snapshot from the EPSS Data and Statistics page, displaying the leading EPSS assessments from the preceding 48-hour timeframe at the moment of capture. It is important to note that, according to EPSS, numerous of these CVEs may not undergo exploitation

Although a basic online calculator is accessible for v1.0, engaging with the latest version necessitates either retrieving a daily CSV document from the EPSS Data and Statistics page, or utilizing the API. EPSS evaluations are not exhibited on the National Vulnerability Database (NVD), which favors CVSS scores, but they are accessible on other vulnerability repositories like VulnDB.

As highlighted in our preceding segment, CVSS scores have not reliably foretold exploitation events historically, hence EPSS, in essence, offers a logical complement — it informs about the likelihood of exploitation, whereas CVSS conveys data regarding the severity. For instance, consider a bug with a CVSS Base score of 9.8 but an EPSS score of 0.8% (indicating that, while severe if exploited, the likelihood of exploitation within the next 30 days is less than 1%). Conversely, another bug might possess a lower CVSS Base score of 6.3, yet an EPSS score of 89.9% – in such a scenario, prioritization would be warranted.

A point the EPSS creators emphasize is not to multiply CVSS scores by EPSS scores. While this formula theoretically yields a severity * threat value, it’s crucial to recognize that a CVSS score is an ordinal categorization. EPSS, as per its originators, communicates distinct particulars from CVSS, suggesting they should be regarded in conjunction but distinctly.

So, is EPSS the perfect ally to CVSS? Potentially so – akin to CVSS, it is provided free of charge, offering valuable insights, although with a few considerations.

What metrics does EPSS precisely evaluate?

EPSS delivers a probability score signifyingThe probability of a specific vulnerability being exploited in general varies. It is not designed to assess the likelihood of your organization being targeted or the consequences of a successful exploit, or the integration of an exploit into a worm or ransomware gang’s arsenal, for example. The anticipated outcome is binary (either exploitation occurs or it does not – although it can be more nuanced: either exploitation occurs or we are uncertain if it has happened), therefore an EPSS rating merely indicates the likelihood of exploitation over the next 30 days. It is important to note the timeframe associated with this assessment. EPSS ratings should be regularly updated, as they are dependent on time-sensitive information. A solitary EPSS rating represents a momentary assessment, not an unchanging metric.

EPSS functions as a ‘pre-threat’ solution

EPSS is an anticipatory, preemptive mechanism. Given the necessary details for a specific CVE, it computes the likelihood that the linked vulnerability will be exploited in the following 30 days. Subsequently, you may choose to consider this likelihood for prioritization, provided the vulnerability has not been exploited yet. Therefore, the system does not offer valuable insights if a vulnerability is actively being exploited, as it functions as a predictive measure. In analogy to logistic regression, it serves little purpose to analyze your data through my model and attempt to promote my product if you had already purchased it six weeks ago. This may seem obvious, yet it is crucial to remember that EPSS ratings do not contribute to prioritization choices for vulnerabilities already exploited.

Lack of clearness

EPSS faces a comparable issue to CVSS regarding transparency, albeit for disparate reasons. EPSS is constructed on a machine learning model, and the underlying code and data is not accessible to the majority of FIRST SIG members, let alone the general public. While the maintainers of EPSS emphasize that “enhancing transparency is one of our objectives,” they also mention that data sharing is restricted due to commercial partners’ request. Additionally, the complexities of the infrastructure to maintain EPSS hinder sharing the model and code.

Assumptions and restrictions

Jonathan Spring, a researcher at Carnegie Mellon University’s Software Engineering Institute, highlights some assumptions that restrict the universal applicability of EPSS. EPSS’s website claims the system gauges “the likelihood (probability) that a software vulnerability will be exploited in the wild.” However, there exist certain generalizations. For instance, “software vulnerability” pertains to a published CVE – though some vendors or bug bounty entities might not use CVEs for prioritization. This could be due to a CVE not being published yet for a specific issue, or the vulnerability being more of a misconfiguration problem, which would not receive a CVE anyway.

Similarly, “exploited” implies exploitation attempts that EPSS and its affiliates observed and documented, and “in the wild” denotes the scope of their observation. The authors of the referenced paper also suggest that reliance on IDS signatures leads to a bias towards network-based attacks on perimeter devices.

Numerical results

Like CVSS, EPSS offers numeric results. However, risk cannot be simplified into a single numerical score, as with CVSS. This principle applies to any effort to combine CVSS and EPSS scores. Instead, users should consider numeric scores alongside a consciousness of context and the platforms’ limitations, which influence score interpretations. Similar to CVSS, EPSS scores are independent figures; they do not provide suggestions or interpretative guidelines.

Potential upcoming drawbacks

The creators of EPSS suggest that adversaries might adapt to the system. For instance, threat actors may add lower-scoring vulnerabilities to their tools, aware that certain organizations may neglect prioritizing these vulnerabilities. Considering EPSS’s usage of machine learning, the authors also warn of potential attempts by attackers to manipulate EPSS scores adversarially by altering input data (such as social media references or GitHub repositories) to inflate scores for specific vulnerabilities.

SSVC, established by Carnegie Mellon University’s Software Engineering Institute (SEI) in partnership with CISA in 2019, significantly differs from CVSS and EPSS as it does not yield a numeric output at all. Instead, it operates as a decision-tree model (in the conventional, logical sense rather than machine learning). The goal is to address what the developers perceive as two key shortcomings of CVSS and EPSS: a) users are left without recommendations or decision-making points and must interpret numerical scores independently; and b) CVSS and EPSS place the vulnerability, rather than the stakeholder, at the core of their assessments.

According to the SSVC whitepaper, the framework is designed to facilitate prioritization decisions by following a decision tree through various branches. For instance, from a vulnerability management perspective, the process starts by answering a query about exploitability: whether there’s no activity, a proof-of-concept, or signs of active exploitation. This leads to assessments concerning exposure (limited, controlled, or public), the potential automation of the kill chain, and ‘value density’ (the resources a threat actor could acquire post-exploitation). Finally, there are considerations regarding safety impact and mission impact. The conclusion of the decision tree presents four possible outcomes: defer, scheduled, out-of-cycle, or immediate.

Figure 2: A sample decision tree from the SSVC demo site

The current version of SSVC encompasses additional roles, such as patch suppliers, coordinators, and triage/publish roles (decisions concerning triage and publishing of new vulnerabilities), each with distinct questions and decision outcomes. For instance, in coordination triage, the potential results are decline, track, and coordinate. The labels and weightings are also craftedto be adaptable according to the preferences and industry of an organization.

After navigating the decision tree, you have the option to export the outcome as either JSON or PDF. The outcome also contains a vector string, a familiar element to those who have read our analysis of CVSS in the previous article. Significantly, this vector string includes a timestamp; some SSVC results require recalibration based on the context. The creators of the SSVC whitepaper recommend revising scores related to the ‘state of exploitation’ decision point daily, as circumstances can change rapidly. In contrast, other decision points like technical impact should remain constant.

As implied by its name, SSVC aims to place stakeholders at the core of decision-making by focusing on stakeholder-specific concerns and outcome-oriented decisions, rather than numerical ratings. One advantage of this approach is the ability to apply the framework to vulnerabilities lacking a CVE or to misconfigurations; another benefit is the adaptability of the framework to cater to the requirements of stakeholders from diverse industries. It is also relatively user-friendly (you can experiment with it here), once you grasp the definitions.

To our understanding, there has been no independent empirical research on the effectiveness of SSVC; only a limited pilot study carried out by the creators of SSVC. The framework also prioritizes simplicity over intricacy in certain aspects. For example, while CVSS features a metric for Attack Complexity, SSVC lacks a corresponding decision point for the ease or frequency of exploitation; the decision point revolves around whether exploitation has occurred and the presence of a proof-of-concept.

Possibly to prevent overcomplicating the decision tree, by default, none of the decision points in any of the SSVC trees offer an ‘unknown’ choice; instead, users are encouraged to make a “reasonable assumption” based on previous occurrences. In specific scenarios, this might skew the final decision, especially concerning decision points beyond an organization’s control (e.g., whether a vulnerability is actively exploited); analysts may be hesitant to ‘guess’ and may lean towards caution.

However, it could be argued that it’s not necessarily a negative aspect that SSVC avoids numerical ratings (although some users might view this as a disadvantage), and it possesses several other favorable aspects: It is designed to be customizable; is entirely open-source; and furnishes clear recommendations as the ultimate output. Like most tools and frameworks we discuss here, a sound approach would be to combine it with others; integrating EPSS and CVSS particulars (and the KEV Catalog, discussed below), where applicable, into a tailored SSVC decision tree is likely to offer a reasonable indication of which vulnerabilities should be given priority.

The KEV Catalog, managed by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), is a continuously updated compilation of CVEs that threat actors are documented to have actively exploited. As of December 2024, the list comprises 1238 vulnerabilities, with information such as CVE-ID, vendor, product, a brief description, recommended action (and a due date, which will be discussed shortly), and a notes section, often containing a link to a vendor advisory.

As outlined in CISA’s Binding Operational Directive 22-01, “federal, executive branch, departments and agencies” are necessitated to address relevant vulnerabilities in the KEV Catalog, alongside other directives, within specific timeframes (six months for CVE-IDs assigned before 2021, two weeks for all others). CISA’s rationale for establishing the KEV Catalog aligns with points highlighted in our previous article: Only a small minority of vulnerabilities are ever exploited, and threat actors do not base their actions on severity ratings to create and execute exploits. Consequently, CISA posits that “known exploited vulnerabilities should be the top priority for remediation…[r]ather than have agencies focus on thousands of vulnerabilities that may never be used in a real-world attack.”

The KEV Catalog is not updated at regular intervals but is refreshed within 24 hours of CISA becoming aware of a vulnerability meeting specified criteria:

- A CVE-ID is present

- There is credible evidence of active exploitation in real-world scenarios

- There is a distinct remedial measure for the vulnerability

According to CISA, evidence of active exploitation – be it attempted or successful – is sourced from in-house open-source research teams, as well as data from security vendors, researchers, partners, US government and international sources, and third-party subscription services. It’s important to note that scanning activities or the existence of a proof-of-concept alone do not warrant the addition of a vulnerability to the Catalog.

Full disclosure: Sophos is a member of the JCDC, a sector of CISA responsible for publishing the KEV Catalog

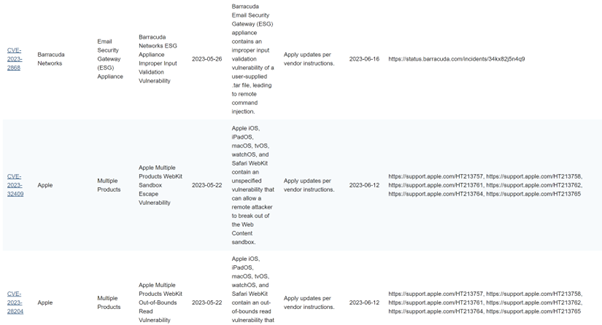

Figure 3: Examples from the KEV Catalog

While primarily targeted at US federal agencies, numerous private sector entities have embraced the list for prioritization purposes. The Catalog offers a straightforward and concise compilation of active threats, available in CSV or JSON formats, which can be easily integrated and, as suggested by CISA, assimilated into a vulnerability management scheme for prioritization. It is stressed by CISA that organizations should not rely exclusively on the Catalog but consider other sources of information as well.

Similar to EPSS, the KEV Catalog operates on a binary premise: if a flaw is listed, it has been exploited; if not, it hasn’t (or, more precisely, the exploitation status is unknown). Nevertheless, KEV lacks a substantial amount of contextual details that could aid organizations in prioritization, particularly in the future as the list grows and becomes more intricate (which it inevitably will; vulnerabilities are only removed from the list if a vendor update introduces an “unforeseen issue of greater impact than the vulnerability itself”).

For instance, the Catalog does not divulge the extent of exploitation. Has a flaw been exploited once, several times, or thousands of times? It fails to provide data on affected sectors or regions, which could be valuable factors for prioritization. It omits details regarding the classification of threat actors exploiting the vulnerability (beyond ransomware actors), or the most recent exploitation occurrence. Similar to our discussion on EPSS, there are concerns about what constitutes a vulnerability and the transparency of data. Regarding the former, a KEV Catalog entry must be associated with a CVE – a criterion that may have limited utility for some organizations

stakeholders – and in relation to the latter, the extent to which it is exploited is confined to what CISA’s associates can witness, and that information is not open for review or validation. Nonetheless, a carefully chosen lineup of vulnerabilities that are believed to have been actively exploited can certainly be beneficial for many entities, offering supplementary insights on which to ground decisions related to mitigation.

It’s apparent that by merging various tools and frameworks, a more comprehensive understanding of risk can be attained, leading to more enlightened prioritization strategies. CVSS provides an evaluation of a vulnerability’s seriousness based on its inherent traits; the KEV Catalog discloses vulnerabilities that threat actors have exploited; EPSS presents the likelihood of threat actors exploiting a vulnerability in the future; and SSVC facilitates decision-making concerning prioritization by considering some of this data within a personalized, stakeholder-specific decision-making model.

To a certain degree, CVSS, EPSS, SSVC, and the KEV Catalog are considered the ‘major players.’ Now, let’s shift our focus to some lesser-known tools and frameworks to see how they measure up. (To keep things clear, we won’t cover systems like CWE, CWSS, CWRAF, and others, as these are specific to weaknesses rather than vulnerabilities and prioritization.)

Manufacturer-specific schemes

Several businesses offer paid services and tools for ranking vulnerabilities to aid in prioritization; some of these may include prediction data akin to EPSS produced by proprietary models, or EPSS ratings partnered with closed-source data. Others utilize CVSS, sometimes merging scores with their own scoring systems, threat intelligence, vulnerability intelligence, and/or details about a customer’s assets and infrastructure. While these solutions may offer a more holistic view of risk and better guidance for prioritization compared to solely relying on CVSS or EPSS, they are typically not publicly accessible and thus cannot be evaluated or assessed.

Product vendors have devised their proprietary systems and disclose their ratings. Microsoft, for instance, has two such systems for vulnerabilities in their products: a Security Update Severity Rating System which, akin to CVSS, offers an overview of a vulnerability’s severity; and the Microsoft Exploitability Index, aimed at evaluating the probability of a vulnerability being exploited. This assessment seems to be based on Microsoft’s analysis of the vulnerability, its exploit difficulty, and historical exploitation trends, though there is insufficient data provided to confirm this.

Similarly, Red Hat utilizes a Severity Ratings system, consisting of four potential ratings along with a computed CVSS Base score. Analogous to the Microsoft systems, this applies solely to vulnerabilities in proprietary products, and the methodology used for calculating the scores remains undisclosed.

CVE Trends (RIP) and substitutes

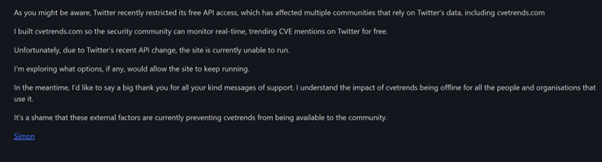

CVE Trends, which is presently inactive due to restrictions imposed by X on its API usage, serves as a community-driven dashboard sourced from X, Reddit, GitHub, and NVD. It displayed the ten most talked-about vulnerabilities based on this amalgamated data.

Figure 4: The CVE Trends dashboard

As demonstrated in the screenshot above, the dashboard exhibited CVSS and EPSS ratings, CVE particulars, as well as sample tweets and Reddit posts, alongside ‘published’ dates and a metric of recent discussion activity over the last few days (or 24 hours).

While CVE Trends could provide insights into the prevalent CVEs within the security community and serve as a source for timely news regarding new vulnerabilities, its utility above and beyond newly emerged, high-impact bugs is limited. It displayed only ten vulnerabilities at a time, and some of these – such as Log4j, evident in the screenshot – were rather aged but remained in discussion due to their prevalence and noteworthiness.

As previously mentioned, CVE Trends is currently inactive, a status that has persisted since mid-2023. Presently, visitors to the platform encounter the following notification, the same one shared as the farewell message on its creator’s Twitter profile:

Figure 5: CVE Trends’ farewell message / tweet

It is uncertain whether X will ease the restrictions on API usage or if Simon J. Bell, the creator of CVE Trends, will explore alternative avenues to restore the platform’s functionality.

Following the shutdown of Bell’s platform, Intruder introduced their adaptation of this tool, currently in beta, also dubbed ‘CVE Trends.’ It includes a ‘Hype score’ ranging from 0 to 100 based on social media activity.

SOCRadar also operates a similar service termed ‘CVE Radar,’ which features details on tweet count, news coverage, and vulnerability-focused repositories within its dashboard. In a commendable gesture, it pays homage to Simon Bell’s work on CVE Trends on its homepage (similar to Intruder’s acknowledgment on its About page). Both CVE Radar and Intruder’s CVE Trends iteration incorporate the content of related tweets, offering a swift overview of social media conversations regarding a particular vulnerability. Whether the developers of these tools plan to integrate other social platforms, given X’s Twitter exodus, remains uncertain.

CVEMap

Debuted in mid-2024, CVEMap represents a relatively recent command-line interface tool developed by ProjectDiscovery thatseeks to consolidate various components of the CVE ecosystem, such as CVSS rating, EPSS rating, vulnerability age, KEV Catalog entries, proof-of-concept data, and more. CVEMap functions as an aggregation tool without providing new information or scores. Yet, the integration of diverse vulnerability data sources into a user-friendly interface, coupled with the ability to filter by product, vendor, and other criteria, may prove beneficial for defenders looking to make informed prioritization decisions based on multiple sources of information.

Security Alert

Security Alert is a platform created to fill a specific void for responders by promptly notifying users of critical, high-impact vulnerabilities through email, SMS, or phone alerts, bypassing the need to wait for security bulletins or CVE releases. This initiative relies on contributions from researchers who submit vulnerability notifications as pull requests to the GitHub repository. The maintenance status of Security Alert’s author is uncertain; the last activity on the GitHub repository was noted in October 2023.

While Security Alert may cater to a specific need, it is not intended for general prioritization.

vPrioritizer

vPrioritizer is an open-source framework enabling users to evaluate and comprehend contextualized risk on a per-asset or per-vulnerability basis by merging asset management with prioritization. This is achieved by leveraging CVSS scores in conjunction with “community analytics” and findings from vulnerability scanners. Despite being highlighted in the SSVC whitepaper in 2019 and showcased at the Black Hat USA Arsenal in 2020, it is unclear whether the developer of vPrioritizer still actively maintains the project; the most recent commit to the GitHub repository dates back to October 2020.

Vulntology

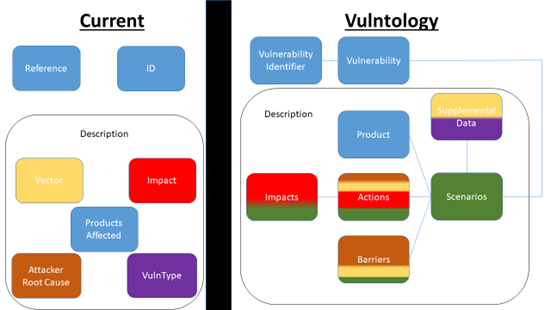

Vulntology represents an initiative led by NIST to classify vulnerabilities, focusing on potential exploitation methods, impact levels, and mitigation possibilities. Its objectives include standardizing the description of vulnerabilities in vendor advisories and security bulletins, enhancing the depth of these descriptions, and promoting the sharing of vulnerability information across language barriers. An illustration of a ‘vulntological representation’ can be found here.

Figure 6: An example of the proposed work by Vulntology, sourced from the project’s GitHub repository

Therefore, Vulntology does not function as a scoring system or decision tree but strives to establish a common language, which could potentially add significant value to vulnerability management if widely adopted. The standardized approach to describing vulnerabilities would be particularly beneficial for evaluating various vendor security advisories, vulnerability intelligence feeds, and other resources. Although it may have long-term implications for vulnerability prioritization and aims to address issues within the vulnerability management domain, it appears that the last commit to the project’s GitHub repository was made in the spring of 2023.

Criminal marketplace data

Lastly, let’s briefly touch on criminal marketplace data and how future research could leverage it for prioritization. In 2014, researchers from the University of Trento conducted a study on the effectiveness of CVSS scores in predicting exploitation. They discovered that CVSS scores do not align with exploit rates but confirmed that taking action against exploits present in black markets leads to the most significant risk reduction. Investigating whether this remains true today could be an intriguing research avenue, considering the growth of exploit markets and the establishment of a substantial underground economy dedicated to trading exploits.

Figure 7: A depiction of a Windows local privilege escalation exploit being offered for sale on a criminal forum

Exploring not only the presence of exploits in criminal marketplaces but also factors like prices, levels of interest, and customer feedback could offer valuable insights for prioritization efforts.

The main challenge lies in accessing these marketplaces and collecting data, as many are exclusive and accessible only through referrals, payments, or reputation. Despite the expansion of the underground economy, it is less centralized now. Although prominent forums serve as initial advertising platforms, crucial details such as pricing are often shared through private messages, and the actual transactions occur via off-channel mediums like Jabber, Tox, and Telegram. More investigation is required to determine the feasibility of using this data source for prioritization.

or perhaps the exploits. Certainly, they play a significant role in the matter, but the crucial aspect is that a vulnerability, when viewed through a remedial lens, is not found in solitude; analyzing its intrinsic characteristics can be beneficial in certain scenarios, however, the most valuable piece of information is how that vulnerability might affect you.

Furthermore, each establishment approaches prioritization uniquely, based on its operations, methodologies, financial resources, and tolerance for risk.

Uniform, off-the-shelf assessments and suggestions often lack logical coherence when evaluating frameworks, and they are even less relevant when seen through the prism of individual entities striving to prioritize remedial actions. Context is paramount. Therefore, regardless of the tools or frameworks utilized, place your organization – not a score or a ranking – at the core of the assessment. It may be beneficial to do this at a more detailed level, considering the dimensions and structure of your entity: prioritizing and contextualizing at a departmental or divisional level. In any case, tailor your approach as much as possible and bear in mind that despite the prominence and acceptance of a framework, its results are merely suggestive.

Some systems, such as CVSS or SSVC, offer in-built options for customization and refinement of outcomes. Conversely, with others like EPSS and the KEV Catalog, customization is not the primary objective, but you can still imbue those results with context, perhaps by integrating that data into other tools and frameworks to gain a comprehensive understanding.

Prioritization extends beyond the scope of the tools discussed here. We have concentrated on them in this series as they constitute a fascinating aspect of vulnerability management, but the foundation for prioritization decisions should ideally stem from a myriad of sources: threat intelligence, vulnerabilities, security stance, controls, risk appraisals, findings from penetration tests and security assessments, among others.

As reiterated from our initial article, while highlighting some of the limitations of these tools and frameworks, we do not intend to undermine the developers or the effort they have invested; our aim has been to provide a fair and balanced evaluation. Crafting frameworks like these demands significant effort and meticulous planning – and they are designed to be utilized; thus, leverage them judiciously when and where appropriate. We trust that this series will equip you to do so in a secure, informed, and efficient manner.