During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a string of dire fires in quick succession prompted an incensed public to call for action from the emerging fire protection sector. Among the specialists, the initial focus lay on “Fire Evacuation Trials”. The first trials centered on individual performance, assessing occupants based on their evacuation speed, sometimes surprising them with an impromptu drill to resemble a real fire. These initial trials often led to injuries for the participants, rather than enhancing their chances of survival. It wasn’t until the introduction of advanced protective measures – such as wider doors, push bars at exits, firebreaks in construction, illuminated exit signs, and more – that survival rates in building fires started to increase. With advancements in protection and the implementation of mandatory fire sprinklers in building codes, survival rates have continuously improved, and “trials” have evolved into scheduled, comprehensive training sessions and prominently displayed evacuation blueprints.

This blog post delves into the current implementation of Phishing “Testing” as a cybersecurity measure in correlation with established fire safety protocols.

Current “Phishing examinations” bear a strong resemblance to the initial “Fire trials”

Google presently abides by regulations (e.g., FedRAMP in the USA) mandating annual “Phishing Tests.” In these compulsory assessments, the Security department devises and dispatches phishing emails to employees, monitors the interaction levels, and educates them on how to avoid falling prey to phishing attempts. These exercises usually involve gathering data on sent emails and the number of employees who “failed” by engaging with the fake link. Additional training is typically provided to employees who do not pass the test. According to the FedRAMP penetration testing guidelines document: “Users represent the final line of defense and should undergo testing.”

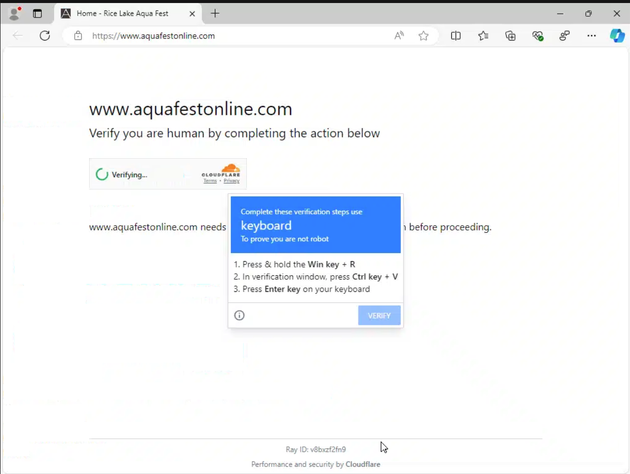

These evaluations mirror the initial “evacuation trials” that occupants of buildings were once subjected to. Participants need to identify the threat, react appropriately on an individual basis, and are informed that any failure is a personal shortcoming rather than a systemic flaw. Moreover, in accordance with FedRAMP guidance, companies are mandated to disable or remove all systemic safeguards during evaluations to artificially increase the chances of an individual clicking on a phishing link.

Below are some of the unfavorable outcomes of these examinations:

-

There is no proof that these assessments lead to a decrease in the frequency of successful phishing attacks;

-

Phishing (or more broadly social manipulation) remains one of the leading methods for attackers to gain entry into organizations.

-

Studies indicate that such evaluations do not effectively thwart individuals from being deceived. A recent research involving 14,000 participants revealed that phishing tests can have a counterproductive impact, as “repeat clickers” consistently fail the tests despite interventions.

-

Certain (e.g, FedRAMP) phishing assessments necessitate bypassing existing anti-phishing safeguards. This can result in a false sense of real risks, enable penetration testing teams to avoid mimicking contemporary attacker strategies, and introduce a risk of allowing the exceptions put in place for the evaluation to remain and be utilized by malicious actors.

-

During these evaluations, Detection and Incident Response (D&R) teams face a significantly increased workload, as users inundate them with numerous unnecessary notifications.

-

Employees become disgruntled by them and perceive security as “tricking them,” which diminishes the trust with our users that is crucial for security teams to implement meaningful systemic enhancements and when.

employees should promptly respond to real security incidents.

In larger firms with various independent services, individuals might face multiple intersecting mandatory phishing assessments, resulting in recurring challenges.

However, can users be the final line of protection?

Teaching individuals to detect phishing or social manipulation with a flawless success rate is probably an impossible mission. There is merit in educating individuals on recognizing phishing and social manipulation to enable them to notify security teams for incident handling. By making sure that even one user reports ongoing attacks, organizations can trigger comprehensive responses that serve as a valuable defensive measure capable of swiftly neutralizing even sophisticated threats. However, similar to the Fire Safety Field’s shift to regular pre-scheduled evacuation drills rather than surprise exercises, the cybersecurity domain should transition to training that diminishes surprises and deceptions, instead focusing on precise guidance on immediate actions upon spotting a phishing email – with special emphasis on identifying and reporting the phishing threat.

In essence – we must halt phishing assessments and implement phishing fire drills.

A “phishing fire drill” would strive to achieve the following:

-

Educate our users on identifying phishing emails

-

Informguiding individuals on how to identify and report phishing emails

-

Permit workers to engage in practicing the identification and reporting of phishing emails in the manner we desire, and

-

Gather valuable data points for auditors, including:

-

The quantity of individuals who successfully completed the phishing email identification practice

-

The duration between the email being opened and the initial report of phishing

-

Timing of the initial alert to the security team (and elapsed time)

-

Number of reports at 1 hour, 4 hours, 8 hours, and 24 hours post-receipt

Illustration

During a phishing simulation, a fabricated email is distributed posing as a phishing attempt with relevant prompts or specific actions to execute. An exemplar excerpt is shown below.

You cannot “repair” individuals, yet you can enhance the tools.

Phishing and Social Engineering tactics remain persistent. As long as human errors and social vulnerability exist, attackers will exploit them. The optimal strategy to address these risks involves focusing on inherently secure systems in the long run and investing in defensive mechanisms such as unphishable credentials (like passkeys) and implementing multi-party authorization for sensitive security scenarios across operational systems. The proactive investments in defensive frameworks like these have shielded Google from password phishing concerns for almost a decade.

Educating staff on promptly notifying security teams regarding ongoing attacks proves to be a crucial component of an all-encompassing security strategy. However, framing this education in a non-confrontational manner is essential, and there is no value in “trapping” individuals for “failing” at their assigned task. Let’s depart from traditional unsuccessful security measures and follow the lead of more experienced industries, like Fire Protection, which have encountered and resolved similar issues through a balanced approach.